Gaucho

The figure of the gaucho is a folk symbol of Argentina, Paraguay,[1] Uruguay, Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, the southern part of Bolivia,[2] and the south of Chilean Patagonia.

According to the Diccionario de la lengua española, in its historical sense a gaucho was a "mestizo who, in the 18th and 19th centuries, inhabited Argentina, Uruguay, and Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil, and was a migratory horseman, and adept in cattle work".

[31] Hence the Uruguayan sociolinguist José Pedro Rona thought the origin of the word was to be sought "on the frontier zone between Spanish and Portuguese, which goes from northern Uruguay to the Argentine province of Corrientes and the Brazilian area between them".

[32] Rona, himself born on a language frontier in pre-Holocaust Europe,[i] was a pioneer of the concept of linguistic borders, and studied the dialects of northern Uruguay where Portuguese and Spanish intermingle.

[41] In sum, according to this theory, gaúcho originated in the Uruguay-Brazil dialect borderlands, deriving from a derisive indigenous word garrucho, then in Spanish lands evolved by accent-shift to gaucho.

"The great natural abundance of the pampa", wrote Richard W. Slatta, with its plethora of cattle, horses, ostriches,[42] and other wild game, meant that a skilled horseman and hunter could live without permanent employment by selling hides, feathers, pelts, and eating free beef.

The gaucho was a born cavalryman,[52][51] and his bravery in the patriot cause in the wars of independence, especially under Artigas and Martín Miguel de Güemes, earned admiration and improved his image.

They approached the troop with such confidence, relaxation, and coolness that they caused great admiration among the European military men, who were seeing for the first time these extraordinary horsemen whose excellent qualities for guerilla warfare and swift surprise they had to endure on many occasions.

[55] Emeric Essex Vidal, the first artist to paint gauchos,[56] noted their mobility (1820): They never conceive any attachment either for the soil or for a master: however well he may pay, and however kindly he may treat them, they leave him at any moment when they take it into their heads, most frequently without even bidding him adieu, or at most saying, "I am going, because I have been with you long enough".

Some restrictions on the gaucho's freedom of movement were imposed under Spanish Viceroy Sobremonte, but they were greatly intensified under Bernardino Rivadavia, and were enforced more vigorously still under Juan Manuel de Rosas.

This time, however, his mobile, lance-wielding horsemen were put down, and decisively, by Uruguayan troops armed with Mauser rifles and Krupp cannon, efficiently deployed by telegraph and rail.

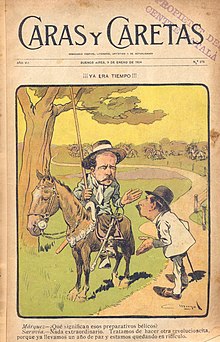

Famously, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, Argentina's second elected president, had written (in Facundo: Civilización y Barbarie) that gauchos, although audacious and skilled in country lore, were brutal, feckless, lived indolently in squalor, and — by upholding the caudillos (provincial strongmen) — were obstacles to national unity.

[99] The turbulent gaucho leaders e.g. the Saravias had connections with the cattlemen over the Brazilian border,[100] where there was much less European immigration;[101] Wire fences did not become common in the borderland until the close of the 19th century.

[102] The revolutionary battles in Brazil ended by 1930 under the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, who disarmed the private gaúcho armies and prohibited the carrying of guns in public.

That he vanished is good for the country, because his Indian blood contained an inferior element.Lugones' lectures, where he canonised Martín Fierro with its quarreling gaucho protagonist, had official support: the president of the Republic and his cabinet attended them,[107] as did prominent members of the traditional ruling classes.

However, wrote a Mexican scholar, in exalting this gaucho Lugones and others were not recreating a real historical character, they were weaving a nationalist myth, for political purposes.

[111] Wrote musicologist Melanie Plesch:The invention of national types, as is well known, involves a fair amount of idealization and fantasy, but the Argentine case presents an idiosyncratic feature: the mythical gaucho seems to have been drawn as an inverted image of the immigrant.

Thus, the immigrant's rapacity was contrasted with the gaucho's disinterestedness, stoicism and spiritual bohemianism, characteristics that had previously been conceptualized as his proverbial laziness and lack of industry.

[112] The iconic gaucho gained traction in popular culture because he appealed to diverse social groups: displaced rural workers; European immigrants anxious to assimilate; traditional ruling classes wanting to affirm their own legitimacy.

[113] At a time when the elite was extolling Argentina as a "white" country, a fourth group, those who possessed dark skins, felt validated by the gaucho's elevation, seeing that his non-white ancestry was too well known to be concealed.

De Martín Fierro a Perón, el emblema imposible de una nación desgarrada (The indomitable gaucho: from Martín Fierro to Perón, the impossible emblem of a torn nation), Raanan Rein wrote:The Argentine military dictatorship used the figure of the gaucho in its propaganda to promote the 1978 FIFA world cup games and the image of Argentina as a peaceful and orderly country.

Hence, wrote Luciano Bornholdt,the myth of the gaúcho was carefully constructed, and he was portrayed not as a poor herder, living a dangerous and dirty life, but as something much more appealing: he was praised as free, yet honest and loyal to his patron, a skilled man, even a hero in the official accounts of regional wars.

[123] By reputation the quintessential gaucho caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas could throw his hat on the ground and scoop it up while galloping his horse, without touching the saddle with his hand.

[124] For the gaucho, the horse was absolutely essential to his survival for, said Hudson: "he must every day traverse vast distances, see quickly, judge rapidly, be ready at all times to encounter hunger and fatigue, violent changes of temperature, great and sudden perils".

The water for mate was heated short of boiling on a stove in a kettle, and traditionally served in a hollowed-out gourd and sipped through a metal straw called a bombilla.

Pulperías were typically located far in the country side and sold items such as yerba mate, liquor, tobacco, sugar, clothing, horse tack, and may other things vital to survival in the countryside.

Advances in technology have led to the incorporation of trucks, all-terrain vehicles, and modern equipment into contemporary operations, but horsemanship is still a crucial skill due to the rugged terrain of the area, as well as to pay homage to the culture.

Genres such as payada make strong use of this spoken word style medium, with performers known as payadors dressing in traditional clothing and exchanging improvised verses in a duel until a winner is clear.

[142] The attire typically associated with gauchos has for the most part disappeared, however the traditional clothing is still sometimes worn to festivals and events, and as work wear in certain estancias that cater to tourism, known as paradores.

The gaucho in some respects resembled members of other nineteenth century rural, horse-based cultures such as the North American cowboy (vaquero in Spanish), huaso of Central Chile, the Peruvian chalan or morochuco, the Venezuelan and Colombian llanero, the Ecuadorian chagra, the Hawaiian paniolo,[143] the Mexican charro, and the Portuguese campino, vaqueiro or even caubói.