Gender neutrality in languages with grammatical gender

At the same time, the newer feminine forms in most such languages are usually derived from the primary masculine term by adding or changing a suffix (such as the German Ingenieurin from Ingenieur, engineer).

Citing German as an example, almost all the names for female professionals end in -in, and because of the suffix, none can consist of a single syllable as some masculine job titles do (such as Arzt, doctor).

By working within the existing lexicon, modern ideas of gender inclusivity are able to advance without developing entirely new explicit gender-neutral forms.

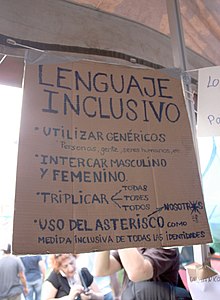

Starting in the 1990s, feminists and others have advocated for more gender-neutral usage, creating modified noun forms which have received mixed reactions.

As in other languages, the masculine word is typically unmarked and only the feminine form requires use of a suffix added to the root to mark it.

[15][16][17] In the 1990s, a form of contraction using a non-standard typographic convention called Binnen-I with capitalization inside the word started to be used (e.g., SekretärIn; SekretärInnen).

Most modern derivatives of the Latin noun homo, however, such as French homme, Italian uomo, Portuguese homem, and Spanish hombre, have acquired a predominantly male denotation, although they are sometimes still used generically, notably in high registers.

In Romanian, however, the cognate om retains its original meaning of "any human person", as opposed to the gender-specific words for "man" and "woman" (bărbat and femeie, respectively).

[33] Some politicians have adopted gender-neutral language to avoid perceived sexism in their speeches; for example, the Mexican president Vicente Fox Quesada was famous for repeating gendered nouns in both their masculine and feminine versions (ciudadanos y ciudadanas).

The capital of Argentina, Buenos Aires, gained attention when they banned the use of 'inclusive language' such as -e, -x, and -@ endings in up to secondary education.

For example, in 2017, Prime Minister Édouard Philippe called for the banning of inclusive language in official documents because it purportedly violated French grammar.

[39] Additionally, the Académie Française does not support the inclusive feminine forms of traditionally masculine job titles, stating their position on their website: L’une des contraintes propres à la langue française est qu’elle n’a que deux genres : pour désigner les qualités communes aux deux sexes, il a donc fallu qu’à l’un des deux genres soit conférée une valeur générique afin qu’il puisse neutraliser la différence entre les sexes.

They risk sowing confusion and disorder in a subtle balance that has been achieved through use, and that it would seem better advised to leave it to usage to make any changes.In this same statement, the Académie Française expressed that if an individual wishes for her job title to reflect her gender, it is her right to name her own identity in personal correspondences.

[40] In contrast to linguistic traditionalism in France, the use of feminine job titles is more widely accepted in the larger Francophonie.

The use of non-gendered job titles in French is common and generally standard practice among the francophones in Belgium and in Canada.

The title mademoiselle has been rejected in public writing by the French government since December 2012, in favour of madame for all adult women, without respect to civil status.

Non-binary French-speakers in Canada have coined a gender-neutral 3rd person pronoun iel as an alternative to the masculine il or feminine elle.

[56][57] Also, due to Brazil's conservative society and reactionarism,[58][59][60] gender neutral language is often seen as a political statement,[61][62] and law proposals against its use,[63] as well as sex education,[64][65] are highly politicized within anti-gender movement.

[69] For example, a female lawyer can be called avvocata or avvocatessa (feminine) but some might prefer to use the word avvocato (masculine).

[71][72] In spite of traditional standards of Italian grammar, some Italians in recent years have opted to start using the pronoun "loro" (a literal translation of English "they"), to refer to people who desire to be identified with a gender neutral pronoun, although this usage may be perceived as incorrect due to the plural agreement of verbs.

Sometimes, this is not the case: актриса (aktrísa, actress), поэтесса (poetéssa, poetess; e.g. Anna Akhmatova insisted on being called поэт (poét, masculine) instead).

The feminine form may be used in less formal context to stress a personal description of the individual: Настя стала учительницей (Nástja stála učítel'nicej, "Nastia became a teacher [f]", informal register).

[81][82] When referring to these mixed-gender nouns, a decision has to be made, based on factors such as meaning, dialect or sometimes even personal preference, whether to use a masculine or feminine pronoun.

Grammatical gender is sometimes shown in other parts of speech by means of mutations, vowel changes and specific word choices.

The Welsh Academy English–Welsh Dictionary explains "it must be reiterated, gender is a grammatical classification, not an indicator of sex; it is misleading and unfortunate that the labels masculine and feminine have to be used, according to tradition.

[89] Some consider the agent suffix -ydd to be more gender neutral than -wr[81] however the Translation Service advises against the use of words ending in -ydd in job titles unless it is natural to do so.

[89] This means that established words such as cyfieithydd "translator" are readily used whereas terms such as rheolydd for "manager" instead of rheolwr or cyfarwyddwraig "(specifically feminine) director" instead of cyfarwyddwr are proscribed by the Service.

With countries that do not have such a close connection with Wales, usually those further away, only one form of the noun is found, for example, Rwsiad "a Russian" (both masculine and feminine).

[82] Ken George has recently suggested a complete set of gender-neutral pronouns in Cornish for referring to non-binary people, based on the forms George believes these pronouns would take if the neuter gender had survived from Proto-Celtic to Middle Cornish (independent *hun, possessive *eydh, infixed *'h, demonstrative *homma, *humma, and prepositional suffix *-es).

[93] Job titles usually have both a masculine and feminine version, the latter usually derived from the former by means of the suffix -es, for example, negesydh "businessman" and negesydhes "businesswoman", skrifennyas "(male) secretary" and skrifenyades "(female) secretary", sodhek "(male) officer" and sodhoges "(female) officer".

The upper sign Wahlarztordination Chirurgie/Allgemeinmedizin , roughly "Private Doctor Consultation Surgery/General medicine", points to the office of a Wahlarzt , a "doctor of choice" who is not paid directly by the health insurance company . This sign uses the masculine Wahlarzt and not WahlärztIn .