Gender pay gap

Additionally, the consequences of the gender pay gap surpass individual grievances, leading to reduced economic output, lower pensions for women, and fewer learning opportunities.

[9][10] The gender pay gap can be a problem from a public policy perspective in developing countries because it reduces economic output and means that women are more likely to be dependent upon welfare payments, especially in old age.

[17] A 2005 meta-analysis by Doris Weichselbaumer and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer of more than 260 published pay gap studies for over 60 countries found that, from the 1960s to the 1990s, raw (non-adjusted) wage differentials worldwide have fallen substantially from around 65% to 30%.

[43] A 2017 study in the American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics found that the growing importance of the services sector has played a role in reducing the gender gap in pay and hours.

By controlling for job characteristics, the analyst introduces collider bias into the analysis, making it impossible to draw valid conclusions about the role of gender discrimination on earnings.

[76][failed verification] These perceptions, along with the factors previously described in the article, contribute to the difficulty of women to ascend to the executive ranks when compared to men in similar positions.

[82] The gender pay gap can be a problem from a public policy perspective because it reduces economic output and means that women are more likely to be dependent upon welfare payments, especially in old age.

[11][12][13] A 2009 report for the Australian Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs argued that in addition to fairness and equity there are also strong economic imperatives for addressing the gender wage gap.

Parental leave, nursing breaks, and the possibility for flexible or part-time schedules are also identified as potential factors limiting women's learning in the workplace.

[94] Other economic models have expanded upon this idea, demonstrating that when pursuing divorce is too costly, the threat of domestic violence may act as a potential method to shift bargaining advantages within a household.

And even if they are, proving a discrimination claim is intrinsically difficult for the claimant and legal action in courts is a costly process, whose benefits down the road are often small and uncertain.

Even in the absence of discrimination and in flexible labor markets, women's relatively high opportunity cost of non-paid-work time and gender-based differences in preferences and constraints can sustain a gender pay gap.

[120] The gender pay gap is calculated on the average weekly ordinary time earnings for full-time employees published by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

[122] Ian Watson of Macquarie University examined the gender pay gap among full-time managers in Australia over the period 2001–2008, and found that between 65 and 90% of this earnings differential could not be explained by a large range of demographic and labor market variables.

Watson also notes that despite the "characteristics of male and female managers being remarkably similar, their earnings are very different, suggesting that discrimination plays an important role in this outcome".

[123] A 2009 report to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs also found that "simply being a woman is the major contributing factor to the gap in Australia, accounting for 60 per cent of the difference between women's and men's earnings, a finding which reflects other Australian research in this area".

This is due to an exponential growth of Brazil's Political Empowerment gender gap, which measures the ratio of females in the parliament and at a ministerial level, that is too large to be counterbalanced by a range of modest improvements across the country's Economic Participation and Opportunity sub-index.

[127] According to data from the Continuous National Household Sample Survey, done by IBGE on the fourth quarter of 2017, 24.3% of the 40.2 million Brazilian workers had completed college, but this proportion was of 14.6% among employed men.

[130] Similarly, a study in the healthcare sector found that women health managers earn 12% less than men at the middle-level and 20% less at the senior level, after adjusting statistically for age, education and other characteristics.

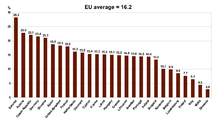

[136]: 15–17, 23 [139] At EU level, the gender pay gap is defined as the relative difference in the average gross hourly earnings of women and men within the economy as a whole.

[citation needed] There were considerable differences between the Member States, with the non-adjusted pay gap ranging from less than 10% in Italy, Slovenia, Malta, Romania, Belgium, Portugal, and Poland to more than 20% in Slovakia, the Netherlands, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Germany, United Kingdom, and Greece and more than 25% in Estonia and Austria.

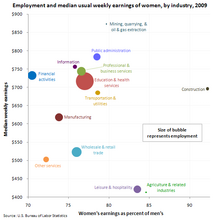

[149][150] The most significant factors associated with the remaining gender pay gap are part-time work, education and occupational segregation (less women in leading positions and in fields like STEM).

[154] The current extent of gender pay gap refers to different factors such as varying working hours and diverse participation in the labor market.

Evidence for the conclusion is the finding that women are entering the workforce in contingent positions for a secondary income and a company need of part-time workers based on mechanizing, outsourcing and subcontracting.

[162] With regards to monthly earnings, including part-time jobs, the gender gap can be explained primarily by the fact that women work few hours than men, but occupation and industry segregation also pay an important role.

[165] In addition, as many women leave the workplace once married or pregnant, the gender gap in pension entitlements is affected too, which in turn impacts the poverty level.

According to Jayoung Yoon, Singapore's aging population and low fertility rates are resulting in more women joining the labor force in response to the government's desire to improve the economy.

[181] A 2015 study compiled by the Press Association based on data from the Office for National Statistics revealed that women in their 20s were out-earning men in their 20s by an average of £1,111, showing a reversal of trends.

[185] The then prime minister David Cameron announced plans to require large firms to disclose data on the gender pay gap among staff.

[194] Beyond overt discrimination, multiple studies explain the gender pay gap in terms of women's higher participation in part-time work and long-term absences from the labor market due to care responsibilities such as motherhood penalty, among other factors.

|

0.12

0.20

0.25

|

0.30

0.35

0.40

|

0.45

0.50

0.55

|

0.60

0.65

0.70

|

0.75

0.80

0.90

|