Gene doping

Genetic enhancement includes gene doping and has potential for abuse among athletes, all while opening the door to political and ethical controversy.

[4][6] This led regulatory authorities in the US and Europe to increase safety requirements in clinical trials even beyond the initial restrictions that had been put in place at the beginning of the biotechnology era to deal with the risks of recombinant DNA.

[7][8] Also in June 2001, a Gene Therapy Working Group, convened by the Medical Commission of the International Olympic Committee noted that "we are aware that there is the potential for abuse of gene therapy medicines and we shall begin to establish procedures and state-of-the-art testing methods for identifying athletes who might misuse such technology".

[4][9] In 2006 interest from athletes in gene doping received widespread media coverage due its mention during the trial of a German coach who was accused and found guilty of giving his athletes performance enhancing drugs without their knowledge; an email in which the coach attempted to obtain Repoxygen was read in open court by a prosecutor.

[1][19] The risks of gene doping would be similar to those of gene therapy: immune reaction to the native protein leading to the equivalent of a genetic disease, massive inflammatory response, cancer, and death, and in all cases, these risks would be undertaken for short-term gain as opposed to treating a serious disease.

[6][7] Alpha-actinin-3 is found only in skeletal muscle in humans, and has been identified in several genetic studies as having a different polymorphism in world-class athletes compared with normal people.

[6] In work published in 2009, scientists administered follistatin via gene therapy to the quadriceps of non-human primates, resulting in local muscle growth similar to the mice.

[22] EPO genes have been successfully inserted into mice and monkeys, and were found to increase hematocrits by as much as 80 percent in those animals.

[22] However, the endogenous and transgene derived EPO elicited autoimmune responses in some animals in the form of severe anemia.

[19] Preproenkephalin has been administered via gene therapy using a replication-deficient herpes simplex virus, which targets nerves, to mice with results good enough to justify a Phase I clinical trial in people with terminal cancer with uncontrolled pain.

[6] The World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) is the main regulatory organization looking into the issue of the detection of gene doping.

[6] For example, Eero Mäntyranta, an Olympic cross country skier, had a mutation which made his body produce abnormally high amounts of red blood cells.

It would be very difficult to determine whether or not Mäntyranta's red blood cell levels were due to an innate genetic advantage, or an artificial one.

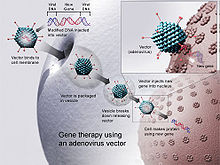

It can be easily distinguished from endogenous DNA because it lacks introns since the transgene will most likely use cDNA that is obtained by reverse transcriptase from RNA, which has removed its intones though RNA splicing leaving only exon-exon junction that include only the coding sequences and some important sequences like promoters since the viral victors has a limited capacity.

[32] Kayser et al. argue that gene doping could level the playing field if all athletes receive equal access.

[33] The high risks associated with gene therapy can be outweighed by the potential of saving the lives of individuals with diseases: according to Alain Fischer, who was involved in clinical trials of gene therapy in children with severe combined immunodeficiency, "Only people who are dying would have reasonable grounds for using it.

"[34] As seen with past cases, including the steroid tetrahydrogestrinone (THG), athletes may choose to incorporate risky genetic technologies into their training regimes.

[3] The mainstream perspective is that gene doping is dangerous and unethical, as is any application of a therapeutic intervention for non-therapeutic or enhancing purposes, and that it compromises the ethical foundation of medicine and the spirit of sport.