Gene duplication

Gene duplications can arise as products of several types of errors in DNA replication and repair machinery as well as through fortuitous capture by selfish genetic elements.

Common sources of gene duplications include ectopic recombination, retrotransposition event, aneuploidy, polyploidy, and replication slippage.

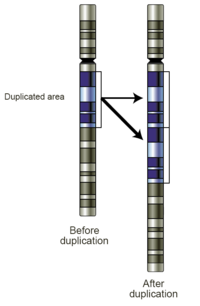

[1] Duplications arise from an event termed unequal crossing-over that occurs during meiosis between misaligned homologous chromosomes.

Ectopic recombination is typically mediated by sequence similarity at the duplicate breakpoints, which form direct repeats.

Transcripts are reverse transcribed to DNA and inserted into random place in the genome, creating retrogenes.

Polyploidy is common in plants, but it has also occurred in animals, with two rounds of whole genome duplication (2R event) in the vertebrate lineage leading to humans.

[15] Polyploidy is also a well known source of speciation, as offspring, which have different numbers of chromosomes compared to parent species, are often unable to interbreed with non-polyploid organisms.

Whole genome duplications are thought to be less detrimental than aneuploidy as the relative dosage of individual genes should be the same.

[19] Older (indirect) studies reported locus-specific duplication rates in bacteria, Drosophila, and humans ranging from 10−3 to 10−7/gene/generation.

[20][21][22] Gene duplications are an essential source of genetic novelty that can lead to evolutionary innovation.

Duplication creates genetic redundancy, where the second copy of the gene is often free from selective pressure—that is, mutations of it have no deleterious effects to its host organism.

[24] Gene duplication is believed to play a major role in evolution; this stance has been held by members of the scientific community for over 100 years.

[25] Susumu Ohno was one of the most famous developers of this theory in his classic book Evolution by gene duplication (1970).

[26] Ohno argued that gene duplication is the most important evolutionary force since the emergence of the universal common ancestor.

[31] Often the resulting genomic variation leads to gene dosage dependent neurological disorders such as Rett-like syndrome and Pelizaeus–Merzbacher disease.

However, many duplications are, in fact, not detrimental or beneficial, and these neutral sequences may be lost or may spread through the population through random fluctuations via genetic drift.

By contrast, orthologous genes present in different species which are each originally derived from the same ancestral sequence.

Paralogs can be identified in single genomes through a sequence comparison of all annotated gene models to one another.

[33] Most gene duplications exist as low copy repeats (LCRs), rather highly repetitive sequences like transposable elements.

The simplest means to identify duplications in genomic resequencing data is through the use of paired-end sequencing reads.