Protocell

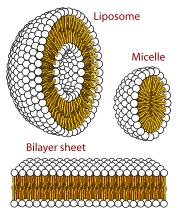

A protocell (or protobiont) is a self-organized, endogenously ordered, spherical collection of lipids proposed as a rudimentary precursor to cells during the origin of life.

[8] Prior to the development of these molecular assemblies, protocells likely employed vesicle dynamics that are relevant to cellular functions, such as membrane trafficking and self-reproduction, using amphiphilic molecules.

[14] Another conceptual model of a protocell relates to the term "chemoton" (short for 'chemical automaton') which refers to the fundamental unit of life introduced by Hungarian theoretical biologist Tibor Gánti.

Gánti conceived the basic idea in 1952 and formulated the concept in 1971 in his book The Principles of Life (originally written in Hungarian, and translated to English only in 2003).

[33] Oleic acid vesicles represent good models of membrane protocells[34] Cohen et al. (2022) suggest that plausible prebiotic production of fatty acids — leading to the development of early protocell membranes — is enriched on metal-rich mineral surfaces, possibly from impact craters, increasing the prebiotic environmental mass of lipids by 102 times.

However, despite this production, the authors state that net fatty acid synthesis would not yield sufficient concentrations for spontaneous membrane formation without significant evaporation of Earth's aqueous environments.

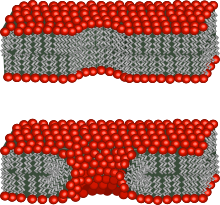

For cellular organisms, the transport of specific molecules across compartmentalizing membrane barriers is essential in order to exchange content with their environment and with other individuals.

Some molecules or particles are too large or too hydrophilic to pass through a lipid bilayer even under these conditions, but can be moved across the membrane through fusion or budding of vesicles,[42] events which have also been observed for freeze-thaw cycles.

[43] This may eventually have led to mechanisms that facilitate movement of molecules to the inside of the protocell (endocytosis) or to release its contents into the extracellular space (exocytosis).

[44] The conclusion is based mainly on the chemistry of modern cells, where the cytoplasm is rich in potassium, zinc, manganese, and phosphate ions, not widespread in marine environments.

Such conditions, the researchers argue, are found only where hot hydrothermal fluid brings the ions to the surface—places such as geysers, mud pots, fumaroles and other geothermal features.

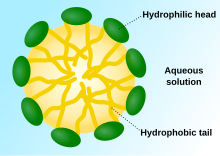

[46] Later, in 2002, it was discovered that by adding montmorillonite to a solution of fatty acid micelles (lipid spheres), the clay sped up the rate of vesicle formation 100-fold.

[46] Some minerals can catalyze the stepwise formation of hydrocarbon tails of fatty acids from hydrogen and carbon monoxide gases—gases that may have been released from hydrothermal vents or geysers.

Fatty acids of various lengths are eventually released into the surrounding water,[47] but vesicle formation requires a higher concentration of fatty acids, so it is suggested that protocell formation started at land-bound hydrothermal freshwater environments such as geysers, mud pots, fumaroles and other geothermal features where water evaporates and concentrates the solute.

[52][58] Because of the "water problem", a primitive ATP synthase and other biomolecules would go through hydrolysis due to the absence of wet-dry cycles at hydrothermal vents, unlike at terrestrial pools.

Secondly, they suggest that the molecular assemblies required to utilize key energetic gradients available at hydrothermal systems were too complex to have been relevant at the origin of life.

Counters to these arguments suggest that the close resemblance between biochemical pathways and geochemical systems at alkaline hydrothermal vents gives merit to the hypothesis, and that selection on these protocells would improve resilience to environmental change, allowing for emergence and distribution.

[63] It has been considered by other researchers that life originating in hydrothermal volcanic ponds exposed to UV radiation, zinc sulfide photocatalysis, and occurrence of continuous wet-dry cycling would not resemble modern biochemistry.

Nick Lane and coauthors state that "alkaline hydrothermal systems tend to precipitate Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions as aragonite and brucite, so their concentrations are typically much lower than mean ocean values.

[67] Another group suggests that primitive cells might have formed inside inorganic clay microcompartments, which can provide an ideal container for the synthesis and compartmentalization of complex organic molecules.

The authors remark that montmorillonite is known to serve as a chemical catalyst, encouraging lipids to form membranes and single nucleotides to join into strands of RNA.

[68] Another way to form primitive compartments that may lead to the formation of a protocell is polyesters membraneless structures that have the ability to host biochemicals (proteins and RNA) and/or scaffold the assemblies of lipids around them.

[7] These droplets can propagate, retaining their internal composition, through shear forces and turbulence in the medium, and could have acted as a means of replicating encapsulation for an early protocell.

However, replication was highly disordered and droplet fusion is common, calling into question coacervates true potential for distinct compartmentalization leading to competition and early Darwinian-selection.

[81] First synthesized in 1963 from simple minerals and basic organics while exposed to sunlight, it is still reported to have some metabolic capabilities, the presence of semipermeable membrane, amino acids, phospholipids, carbohydrates and RNA-like molecules.

[81][82][83] In a similar synthesis experiment a frozen mixture of water, methanol, ammonia and carbon monoxide was exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

[84] The investigating scientist considered these globules to resemble cell membranes that enclose and concentrate the chemistry of life, separating their interior from the outside world.

Formed in distilled water (as well as on agar gel) under the influence of an electric field, they lack protein, amino acids, purine or pyrimidine bases, and certain enzyme activities.

[88] The creation of a basic unit of life is the most pressing ethical concern, although the most widespread worry about protocells is their potential threat to human health and the environment through uncontrolled replication.

Scientists in the field emphasize the importance of further hypothesis based experimentation over theoretical conjecture to more concretely constrain the prebiotic plausibility of different protocell morphologies, geologic conditions, and synthetic schemes.