Horizontal gene transfer

Its study, however, is hindered by the complexity of eukaryotic genomes and the abundance of repeat-rich regions, which complicate the accurate identification and characterization of transferred genes.

Horizontal genetic transfer was then described in Seattle in 1951, in a paper demonstrating that the transfer of a viral gene into Corynebacterium diphtheriae created a virulent strain from a non-virulent strain,[26] simultaneously revealing the mechanism of diphtheria (that patients could be infected with the bacteria but not have any symptoms, and then suddenly convert later or never),[27] and giving the first example for the relevance of the lysogenic cycle.

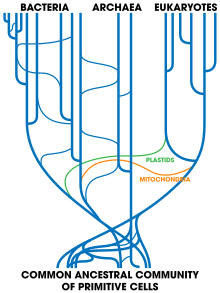

[29][30] In the mid-1980s, Syvanen[31] postulated that biologically significant lateral gene transfer has existed since the beginning of life on Earth and has been involved in shaping all of evolutionary history.

As Bapteste et al. (2005) observe, "additional evidence suggests that gene transfer might also be an important evolutionary mechanism in protist evolution.

[38] Aaron Richardson and Jeffrey D. Palmer state: "Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) has played a major role in bacterial evolution and is fairly common in certain unicellular eukaryotes.

"[39] Due to the increasing amount of evidence suggesting the importance of these phenomena for evolution (see below) molecular biologists such as Peter Gogarten have described horizontal gene transfer as "A New Paradigm for Biology".

[43] Horizontal transposon transfer (HTT) refers to the passage of pieces of DNA that are characterized by their ability to move from one locus to another between genomes by means other than parent-to-offspring inheritance.

[46] On the transposable element side, spreading between genomes via horizontal transfer may be viewed as a strategy to escape purging due to purifying selection, mutational decay and/or host defense mechanisms.

[51] HTT detection is a difficult task because it is an ongoing phenomenon that is constantly changing in frequency of occurrence and composition of TEs inside host genomes.

[55][56] Transposition and horizontal gene transfer, along with strong natural selective forces have led to multi-drug resistant strains of S. aureus and many other pathogenic bacteria.

[5] A prime example concerning the spread of exotoxins is the adaptive evolution of Shiga toxins in E. coli through horizontal gene transfer via transduction with Shigella species of bacteria.

[12] For example, horizontally transferred genetic elements play important roles in the virulence of E. coli, Salmonella, Streptococcus and Clostridium perfringens.

[5] In prokaryotes, restriction-modification systems are known to provide immunity against horizontal gene transfer and in stabilizing mobile genetic elements.

[65][66] In a study on the effects of long-term exposure of simulated microgravity on non-pathogenic E. coli, the results showed transposon insertions occur at loci, linked to SOS stress response.

[67] When the same E. coli strain was exposed to a combination of simulated microgravity and trace (background) levels of (the broad spectrum) antibiotic (chloramphenicol), the results showed transposon-mediated rearrangements (TMRs), disrupting genes involved in bacterial adhesion, and deleting an entire segment of several genes involved with motility and chemotaxis.

In order for a bacterium to bind, take up and recombine exogenous DNA into its chromosome, it must become competent, that is, enter a special physiological state.

[73] Competence for transformation is typically induced by high cell density and/or nutritional limitation, conditions associated with the stationary phase of bacterial growth.

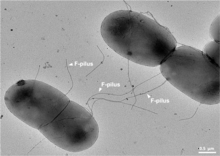

[89][90] The archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus, when UV irradiated, strongly induces the formation of type IV pili which then facilitates cellular aggregation.

The proteins encoded by the ups operon are employed in UV-induced pili assembly and cellular aggregation leading to intercellular DNA exchange and homologous recombination.

"Sequence comparisons suggest recent horizontal transfer of many genes among diverse species including across the boundaries of phylogenetic 'domains'.

[141] Alongside non-antibiotic pharmaceuticals, other compounds relevant to antibiotic resistance have been tested such as malachite green, ethylbenzene, styrene, 2,4-dichloroaniline, trioxymethylene, o-xylene solutions, p-nitrophenol (PNP), p-aminophenol (PAP), and phenol (PhOH).

[142] The cause of this is the organic compounds used for textile dying (o-xylene, ethylbenzene, trioxymethylene, styrene, 2,4-dichloroaniline, and malachite green)[142] raising the frequency of conjugative transfer when bacteria and plasmid (with donor) are introduced in the presence of these molecules.

While much remains to be understood about how promiscuous DNA undergoes movement and transfer, numerous experiments have pointed to plastid sequences, ptDNA, as a key player.

[151][152][153] Plasmids, with their mobile nature and crucial role in horizontal gene transfer, are seen as a significant element in DNA that exchanges genetic information.

[166] Indeed, it was while examining the new three-domain model of life that horizontal gene transfer arose as a complicating issue: Archaeoglobus fulgidus was seen as an anomaly with respect to a phylogenetic tree, based upon the encoding for the enzyme HMGCoA reductase; the organism in question is a definite Archaean, with all the cell lipids and transcription machinery that are expected of an Archaean, but whose HMGCoA genes are of bacterial origin.

(In contrast, multicellular eukaryotes have mechanisms to prevent horizontal gene transfer, including separated germ cells.)

If there had been continued and extensive gene transfer, there would be a complex network with many ancestors, instead of a tree of life with sharply delineated lineages leading back to a LUCA.

[171][172] The acquisition of new genes has the potential to disorganize the other genetic elements and hinder the function of the bacterial cell, thus affecting the competitiveness of bacteria.

Consequently, bacterial adaptation lies in a conflict between the advantages of acquiring beneficial genes, and the need to maintain the organization of the rest of its genome.

Overrepresentation of hotspots with fewer mobile genetic elements in naturally transformable bacteria suggests that homologous recombination and horizontal gene transfer are tightly linked in genome evolution.