g factor (psychometrics)

However, empirical research on the nature of g has also drawn upon experimental cognitive psychology and mental chronometry, brain anatomy and physiology, quantitative and molecular genetics, and primate evolution.

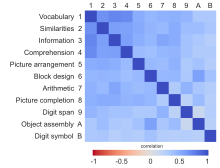

[9] In a famous research paper published in 1904,[10] he observed that children's performance measures across seemingly unrelated school subjects were positively correlated.

However, he thought that the best indicators of g were those tests that reflected what he called the eduction of relations and correlates, which included abilities such as deduction, induction, problem solving, grasping relationships, inferring rules, and spotting differences and similarities.

However, this was more of a metaphorical explanation, and he remained agnostic about the physical basis of this energy, expecting that future research would uncover the exact physiological nature of g.[22] Following Spearman, Arthur Jensen maintained that all mental tasks tap into g to some degree.

[17] He argued that g cannot be described in terms of the item characteristics or information content of tests, pointing out that very dissimilar mental tasks may have nearly equal g loadings.

[23] He also suggested that given the associations between g and elementary cognitive tasks, it should be possible to construct a ratio scale test of g that uses time as the unit of measurement.

[24] The so-called sampling theory of g, originally developed by Edward Thorndike and Godfrey Thomson, proposes that the existence of the positive manifold can be explained without reference to a unitary underlying capacity.

[39][52] This approach has been criticized by psychologist Lazar Stankov in the Handbook of Understanding and Measuring Intelligence, who councluded "Correlations between the g factors from different test batteries are not unity.

[59] and Tucker-Drob (2009)[60] have pointed out, dividing the continuous distribution of intelligence into an arbitrary number of discrete ability groups is less than ideal for examining SLODR.

He applied such a factor model to a nationally representative data of children and adults in the United States and found consistent evidence for SLODR.

As opposed to most research on the topic, this work made it possible to study ability and age variables as continuous predictors of the g saturation, and not just to compare lower- vs. higher-skilled or younger vs. older groups of testees.

At the level of individual employees, the association between job prestige and g is lower – one large U.S. study reported a correlation of .65 (.72 corrected for attenuation).

[83] Additionally, supervisor rating of job performance is influenced by different factors, such as halo effect,[84] facial attractiveness,[85] racial or ethnic bias, and height of employees.

In other words, people high in GCA are capable to learn faster and acquire more job knowledge easily, which allow them to perform better.

In a daily basis, employees are exposed constantly to challenges and problem solving tasks, which success depends solely on their GCA.

For example, Viswesvaran, Ones and Schmidt (1996)[90] argued that is quite impossible to obtain perfect measures of job performance without incurring in any methodological error.

[96][97] In 2006, Psychological Review published a comment reviewing Kanazawa's 2004 article by psychologists Denny Borsboom and Conor Dolan that argued that Kanazawa's conception of g was empirically unsupported and purely hypothetical and that an evolutionary account of g must address it as a source of individual differences,[98] and in response to Kanazawa's 2010 article, psychologists Scott Barry Kaufman, Colin G. DeYoung, Deirdre Reis, and Jeremy R. Gray published a study in 2011 in Intelligence of 112 subjects taking a 70-item computer version of the Wason selection task (a logic puzzle) in a social relations context as proposed by evolutionary psychologists Leda Cosmides and John Tooby in The Adapted Mind,[99] and found instead that "performance on non-arbitrary, evolutionarily familiar problems is more strongly related to general intelligence than performance on arbitrary, evolutionarily novel problems".

Behavioral genetic research has also established that the shared (or between-family) environmental effects on g are strong in childhood, but decline thereafter and are negligible in adulthood.

Many researchers believe that very large samples will be needed to reliably detect individual genetic polymorphisms associated with g.[39][111] However, while genes influencing variation in g in the normal range have proven difficult to find, many single-gene disorders with intellectual disability among their symptoms have been discovered.

[112] It has been suggested that the g loading of mental tests have been found to correlate with heritability,[32] but both the empirical data and statistical methodology bearing on this question are matters of active controversy.

[2] Small but relatively consistent associations with intelligence test scores include also brain activity, as measured by EEG records or event-related potentials, and nerve conduction velocity.

[120][121] A review and meta-analysis of general intelligence, however, found that the average correlation among cognitive abilities was 0.18 and suggested that overall support for g is weak in non-human animals.

Non-human models of g such as mice are used to study genetic influences on intelligence and neurological developmental research into the mechanisms behind and biological correlates of g.[123] Similar to g for individuals, a new research path aims to extract a general collective intelligence factor c for groups displaying a group's general ability to perform a wide range of tasks.

[124] Definition, operationalization and statistical approach for this c factor are derived from and similar to g. Causes, predictive validity as well as additional parallels to g are investigated.

[126] Cross-cultural studies indicate that the g factor can be observed whenever a battery of diverse, complex cognitive tests is administered to a human sample.

Notwithstanding the different research traditions in which psychometric tests and Piagetian tasks were developed, the correlations between the two types of measures have been found to be consistently positive and generally moderate in magnitude.

It has showed that individuals identified by standardized tests as intellectually gifted in early adolescence accomplish creative achievements (for example, securing patents or publishing literary or scientific works) at several times the rate of the general population, and that even within the top 1 percent of cognitive ability, those with higher ability are more likely to make outstanding achievements.

[159] Joseph L. Graves Jr. and Amanda Johnson have argued that g "...is to the psychometricians what Huygens' ether was to early physicists: a nonentity taken as an article of faith instead of one in need of verification by real data.

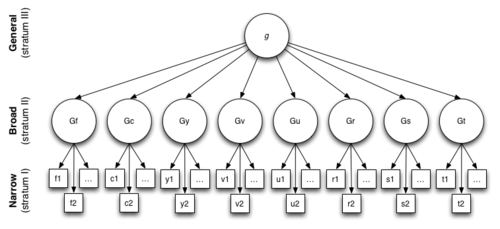

[2][43][161] Gf can be thought to primarily consist of current reasoning and problem solving capabilities, while Gc reflects the outcome of previously executed cognitive processes.

According to this model, the g factor is a useful concept with respect to individual differences but its explanatory power is limited when the focus of investigation is either brain physiology, or, especially, the effect of social trends on intelligence.