Gentile Budrioli

Budrioli drew attention from her contemporaries for her great skill in healing and she became a close friend of Ginevra Sforza, the wife of Bologna's ruler Giovanni II Bentivoglio.

Budrioli's rise to prominence drew the envy of others and in 1498 she was accused of witchcraft after she failed to save one of Bentivoglio's sons from an unknown disease.

At her trial, numerous people came out to support the claims of her being a witch, including her own husband Alessandro, who had staunchly opposed her scientific interests.

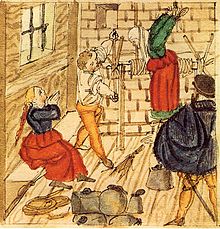

Budrioli was simultaneously hanged and burnt alive in front of a crowd of onlookers at the Piazza San Domenico [it] in Bologna.

[6] Budrioli married the rich notary Alessandro Cimieri,[1][7][8] who owned a home in the Torresotto di Porta Nuova, opposite the Basilica of Saint Francis in Bologna.

[9] Emerging from the surviving sources as a rich, educated and beautiful woman,[1] Budrioli found her married life with Cimieri to be boring.

[6] Budrioli's expertise and her friendship with Sforza allowed her to quickly rise through the ranks in the city and she was before long made a councilor at Bentivoglio's court.

[6] Executing Budrioli as a witch was perhaps a scheme on Bentivoglio's part to improve his relationship with Pope Alexander VI, who at the time threatened to place Bologna under papal control.

[4] Shortly after Budrioli was imprisoned, the Inquisition judges raided her home and "discovered evidence" of witchcraft, such as traces of blood, an assortment of cloaks, ampules with various liquids and an altar.

[6] After the trial, the inquisitors made a second search of her residence and found further evidence that they had somehow missed the first time, including desecrated holy symbols, another altar with images of Lucifer, twelve bags containing human organs, and bones stolen from a cemetery.

[6] After several days of horrific torture[1][3][6] and just before the interrogators were going to begin removing her limbs,[9] Budrioli confessed to having practiced the occult for two decades, a crime she was not guilty of.

[1][2][3] Budrioli was in 2018 cited by the Italian writer Barbara Baraldi as one of many women throughout history who had to pay a steep price for being ahead of their time.