Geology of Titan

[9] Based on the observations, scientists announced "definitive evidence of lakes filled with methane on Saturn's moon Titan" in January 2007.

[12] Overall, the Cassini radar observations have shown that lakes cover only a small percentage of the surface, making Titan much drier than Earth.

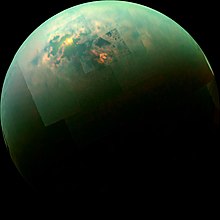

[16][17] On July 8, 2009, Cassini's VIMS observed a specular reflection indicative of a smooth, mirror-like surface, off what today is called Jingpo Lacus, a lake in the north polar region shortly after the area emerged from 15 years of winter darkness.

Specular reflections are indicative of a smooth, mirror-like surface, so the observation corroborated the inference of the presence of a large liquid body drawn from radar imaging.

[20] In contrast, the northern hemisphere's Ligeia Mare was initially mapped to depths exceeding 8 m, the maximum discernable by the radar instrument and the analysis techniques of the time.

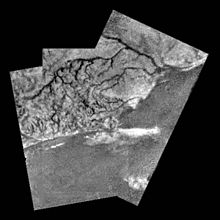

Analysis of the received altimeter echoes showed that the channels are located in deep (up to ~570 m), steep-sided, canyons and have strong specular surface reflections that indicate they are currently filled with liquid.

Elevations of the liquid in these channels are at the same level as Ligeia Mare to within a vertical precision of about 0.7 m, consistent with the interpretation of drowned river valleys.

Specular reflections are also observed in lower order tributaries elevated above the level of Ligeia Mare, consistent with drainage feeding into the main channel system.

Vid Flumina canyons are thus drowned by the sea but there are a few isolated observations to attest to the presence of surface liquids standing at higher elevations.

[25][26] On September 3, 2014, NASA reported studies suggesting methane rainfall on Titan may interact with a layer of icy materials underground, called an "alkanofer", to produce ethane and propane that may eventually feed into rivers and lakes.

[27] In 2016, Cassini found the first evidence of fluid-filled channels on Titan, in a series of deep, steep-sided canyons flowing into Ligeia Mare.

[44] In December 2008, astronomers announced the discovery of two transient but unusually long-lived "bright spots" in Titan's atmosphere, which appear too persistent to be explained by mere weather patterns, suggesting they were the result of extended cryovolcanic episodes.

[46] Prior to Cassini, scientists assumed that most of the topography on Titan would be impact structures, yet these findings reveal that similar to Earth, the mountains were formed through geological processes.

The mountainous ridges observed in some regions can be explained as heavily degraded scarps of large multi-ring impact structures or as a result of the global contraction due to the slow cooling of the interior.

Even in this case, Titan may still have an internal ocean made of the eutectic water–ammonia mixture with a temperature of 176 K (−97 °C), which is low enough to be explained by the decay of radioactive elements in the core.

[40][48] In March 2009, structures resembling lava flows were announced in a region of Titan called Hotei Arcus, which appears to fluctuate in brightness over several months.

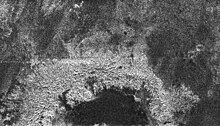

[50] Crater-like landforms possibly formed via explosive, maar-like or caldera-forming cryovolcanic eruptions have been identified in Titan's polar regions.

[51] These formations are sometimes nested or overlapping and have features suggestive of explosions and collapses, such as elevated rims, halos, and internal hills or mountains.

This means that cryovolcanism on Titan would require a large amount of additional energy to operate, possibly via tidal flexing from nearby Saturn.

[45] The low-pressure ice, overlaying a liquid layer of ammonium sulfate, ascends buoyantly, and the unstable system can produce dramatic plume events.

Titan is resurfaced through the process by grain-sized ice and ammonium sulfate ash, which helps produce a wind-shaped landscape and sand dune features.

Titan's modern geology would have formed only after the crust thickened to 50 kilometers and thus impeded constant cryovolcanic resurfacing, with any cryovolcanism occurring since that time producing much more viscous water magma with larger fractions of ammonia and methanol; this would also suggest that Titan's methane is no longer being actively added to its atmosphere and could be depleted entirely within a few tens of millions of years.

Recent computer simulations indicate that the dunes may be the result of rare storm winds that happen only every fifteen years when Titan is in equinox.

[58][60][64] Studies of dunes' composition in May 2008 revealed that they possessed less water than the rest of Titan, and are thus most likely derived from organic soot like [disputed – discuss] hydrocarbon polymers clumping together after raining onto the surface.

The "stickiness" might make it difficult for the generally mild breeze close to Titan's surface to move the dunes although more powerful winds from seasonal storms could still blow them eastward.

[67] Around equinox, strong downburst winds can lift micron-sized solid organic particles up from the dunes to create Titanian dust storms, observed as intense and short-lived brightenings in the infrared.

2 . [ 3 ] (September 11, 2017)