Geophilus flavus

G. flavus occurs in a range of habitats across central Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand and other tropical regions.

[14] The species is widely distributed across regions of Europe, North America and Australia, in suitable local environments such as grassy woodlands and forests.

[7] First, a courting ritual takes place, involving a series of defensive postures and tapping of the legs and antennae on the extremities of the partner.

[4] Unlike other subgroups of centipede, such as Lithobiomorphs, Geophilomorphs actively seek out their prey by searching through leaf litter and mineral soil.

[4] Generalised trophic cascades, indirect food web maps, indicate that predatory invertebrates such as G.flavus have a significant impact on energy and nutrient transfer.

[18] In periods of increased temperature and soil dryness as a result of season or from ongoing climate change, G. flavus displays higher rates of food consumption.

[18] These decomposition processes increase the production of bacteria and fungi, key dietary components of the secondary consumers that G. flavus preys upon.

[19] Conversely, during colder months when prey is less abundant and G. flavus is less active, feeding interactions increase across the entire soil community.

[19] Gut content analysis of the centipede reveals high levels of lumbricid and enchytraeid proteins, nutrient markers of small soil earthworms.

[5] They play a key role in maintaining ecological stability in small-scale soil communities by managing smaller prey populations.

[3] G. flavus inhabits a diverse range of organic structures including soil, rocks, trees, bark and decomposing leaf litter.

[20] The texture and thickness of the leaf litter above the soil surface provides structural niches which facilitate microhabitats and a diversity of small invertebrates that G.flavus hunts.

[21] The nature and structure of the habitat is a large determinant of predator-prey relationships, as denser organic layers increase the search time required for centipedes to locate prey.

[10] G. flavus moves through the soil similarly to earthworms, expanding their length forward, and then contracting in order to pull their body towards their head.

[5] The highly adjustable fat body allows G.flavus to maximise prey abundance when environments are warmer, retaining nutrients for later conversion, usually during hibernation periods.

[5] To prove this, researchers collected centipedes from their habitats and placed them into artificial environments which simulated temperature and humidity conditions of a particular season.

Researchers showed that the fat body in centipedes was constituted by irregular lobular masses of adipocytes, containing organelles responsible for nutrient synthesis.

[23] The study somewhat refutes this claim, hypothesising that G.flavus may have been introduced through the East of Urals several decades ago based on recent distribution and botanical reports.

[23] The study also notes that G.flavus may have been falsely categorised as G.proximous in previous USSR reports, making it unclear whether or not the species is new to Western Siberia.

[15] These descriptions largely aligned with previous documentation by De Geer in 1778, stipulating antennae more than 3 times as long as the head and usually less than 60 leg bearing segments.

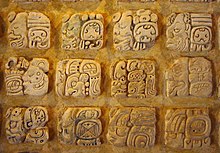

[24] This connection was likely made as centipedes often reside in dark, wet places like caves, which are considered to be liminal entrances to the underground realm by Mayan culture.