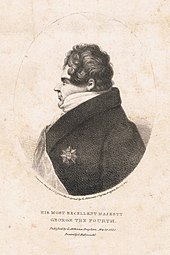

George IV

He excluded Caroline from his coronation and asked the government to introduce the unpopular Pains and Penalties Bill in an unsuccessful attempt to divorce her.

[5] At the age of 18, Prince George was given a separate establishment, and in dramatic contrast to his prosaic, scandal-free father, threw himself with zest into a life of dissipation and wild extravagance involving heavy drinking and numerous mistresses and escapades.

George's relationship with Fitzherbert was suspected, and revelation of the illegal marriage would have scandalised the nation and doomed any parliamentary proposal to aid him.

In the House of Commons, Charles James Fox declared his opinion that Prince George was automatically entitled to exercise sovereignty during the King's incapacity.

A contrasting opinion was held by the prime minister, William Pitt the Younger, who argued that, in the absence of a statute to the contrary, the right to choose a regent belonged to Parliament alone.

[22] Following the passage of preliminary resolutions Pitt outlined a formal plan for the regency, suggesting that Prince George's powers be greatly limited.

Prince George denounced Pitt's scheme by declaring it a "project for producing weakness, disorder, and insecurity in every branch of the administration of affairs".

[14][19] Prince George's debts continued to climb, and his father refused to aid him unless he married his cousin Princess Caroline of Brunswick.

[27] George's mistresses included Mary Robinson, an actress whom he paid to leave the stage;[28] Grace Elliott, the divorced wife of a physician;[29][30] and Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey, who dominated his life for some years.

[34] Anthony Camp, Director of Research at the Society of Genealogists, has dismissed the claims that George IV was the father of Ord, Hervey, Hampshire and Candy as fictitious.

The Lords Commissioners appointed by the letters patent, in the name of the King, then signified the granting of Royal Assent to a bill that became the Regency Act 1811.

Possibly using the failure of the two peers as a pretext, George immediately reappointed the Perceval administration, with Lord Liverpool as prime minister.

[45] The Tories, unlike Whigs such as Lord Grey, sought to continue the vigorous prosecution of the war in Continental Europe against the powerful and aggressive Emperor of the French, Napoleon I.

In 1814, Caroline left the United Kingdom for continental Europe, but she chose to return for her husband's coronation and to publicly assert her rights as queen consort.

Goderich left office in 1828, to be succeeded by Wellington, who had by that time accepted that the denial of some measure of relief to Roman Catholics was politically untenable.

[60][61] George was never as friendly with Wellington as he had been with Canning and chose to annoy the Duke by pretending to have fought at Waterloo disguised as a German general.

Under pressure from his fanatically anti-Catholic brother Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the King withdrew his approval and in protest the Cabinet resigned en masse on 4 March.

While still Prince of Wales, he had become obese through his huge banquets and copious consumption of alcohol, making him the target of ridicule on the rare occasions that he appeared in public;[64] by 1797, his weight had reached 17 stone 7 pounds (111 kg; 245 lb).

"[1] By December 1828, like his father, George was almost completely blind from cataracts, and had such severe gout in his right hand and arm that he could no longer sign documents.

[67] George took laudanum to counteract severe bladder pains, which left him in a drugged and mentally impaired state for days on end.

Now largely confined to his bedchambers, having completely lost sight in one eye and describing himself "as blind as a beetle", he was forced to approve legislation with a stamp of his signature in the presence of witnesses.

[71] Attacks of breathlessness due to dropsy forced him to sleep upright in a chair, and doctors frequently tapped his abdomen in order to drain excess fluid.

[70] Writing to Maria Fitzherbert in June, the King's doctor, Sir Henry Halford, noted "His Majesty's constitution is a gigantic one, and his elasticity under the most severe pressure exceeds what I have ever witnessed in thirty-eight years' experience.

[74] George dictated his will in May and became very devout in his final months, confessing to an archdeacon that he repented of his dissolute life, but hoped mercy would be shown to him as he had always tried to do the best for his subjects.

[73] While Halford only informed the Cabinet on 24 June that "the King's cough continues with considerable expectoration", he privately told his wife that "things are coming to a conclusion ...

According to Halford, following his arrival and that of Sir William Knighton, the King's "lips grew livid, and he dropped his head on the page's shoulder ...

[83] He wore darker colours than had been previously fashionable as they helped to disguise his size, favoured pantaloons and trousers over knee breeches because they were looser, and popularised a high collar with neck cloth because it hid his double chin.

[85] During the political crisis caused by Catholic emancipation, the Duke of Wellington said that George was "the worst man he ever fell in with his whole life, the most selfish, the most false, the most ill-natured, the most entirely without one redeeming quality".

[87] Wellington's true feelings were probably somewhere between these two extremes; as he said later, George was "a magnificent patron of the arts ... the most extraordinary compound of talent, wit, buffoonery, obstinacy, and good feeling—in short a medley of the most opposite qualities, with a great preponderance of good—that I ever saw in any character in my life.

King's Cross, now a major transport hub sitting on the border of Camden and Islington in north London, takes its name from a short-lived monument erected to George IV in the early 1830s.