Georgian Dublin

Georgian Dublin is a phrase used in terms of the history of Dublin that has two interwoven meanings: Though, strictly speaking, Georgian architecture could only exist during the reigns of the four Georges, it had its antecedents prior to 1714 and its style of building continued to be erected after 1830, until replaced by later styles named after the then monarch, Queen Victoria, i.e. Victorian.

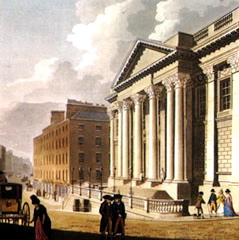

The new Irish Houses of Parliament, designed by Edward Lovett Pearce, also faced onto College Green, while from College Green a new widened Dame Street led directly down to the medieval Christchurch Cathedral, Dublin, past Dublin Castle and the Royal Exchange, the latter a new building.

While the rebuilding by the Wide Streets Commission fundamentally changed the streetscape in Dublin, a property boom led to additional building outside the central core.

[2] Such was the prestige of the street that many of the most senior figures in Irish 'establishment' society, peers of the realm, judges, barristers, bishops bought houses here.

Under the anti-Catholic Penal Laws, Roman Catholics, though the overwhelming majority in Ireland, were harshly discriminated against, barred from holding property rights or from voting in parliamentary elections until 1793.

However, when the Earl of Kildare chose to move to a new large ducal palace built for him on what up to that point was seen as the inferior southside, he caused shock.

[4] Although the Irish Parliament was composed exclusively of representatives of the Anglo-Irish Ascendency, the established ruling minority Protestant community in Ireland, it did show significant sparks of independence, most notably the achievement of full legislative independence in 1782, where all the restrictions previously surrounding the powers of the new parliament in College Green, notably Poynings' Law were repealed.

In 1800, under pressure from the British Government of Mr. Pitt, in the wake of the rebellion of the last years of the century, which was aided and abetted by the French invasion in support of the rebels Dublin Castle administration of the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland both the House of Commons and the House of Lords passed the Irish Act of Union, uniting both the Kingdom of Ireland and its parliament with the Kingdom of Great Britain and its parliament in London.

As a result, from 1 January 1801 Dublin found itself without a parliament with which to draw hundreds of peers and bishops, along with their thousands of servants.

Daisy, the Countess of Fingall, in her regularly republished memoirs Seventy Years Young, wrote in the 1920s of the disappearance of that world and of her change from a big townhouse in Dublin, full of servants to a small flat with one maid.

(Curiously, in the 1990s, new wealthy businessmen such as Sir Tony O'Reilly and Dermot Desmond began returning to live in former offices they had bought and converted back into homes.)

These plans were put on hold in 1939 due to the outbreak of World War II and a lack of capital and investment and had been essentially forgotten about by 1945.

[5] The tenements came to symbolise Dublin's urban poverty, with the focus being on clearing the inner-city slums and demolishing these Georgian structures under the building code as dangerous.

During this period, a number of old houses in poor repair, which had been refused planning permission, caught fire and burnt to the ground, paved the way for redevelopment.

Perhaps the biggest irony for some is that residence that marked the move of the aristocrats from the northside to the southside (where the wealthier Dubliners have remained to this day), and that in some ways embodied Georgian Dublin, Leinster House, home of the Duke of Leinster, ended up as the parliament of independent republican Ireland; but his family also produced the republican leader Lord Edward Fitzgerald.

The decision in the late 1950s to demolish a row of Georgian houses in Kildare Place and replace them with a brick wall was greeted with jubilation by a republican minister at the time, Kevin Boland, who said they stood for everything he opposed.

A ceiling from the Dublin townhouse of Viscount Powerscourt , showing the splendour of Georgian decoration. His former townhouse was sensitively turned into a shopping centre in the 1980s.