History of the Jews in Germany

On 10 November 1938, the state police and Nazi paramilitary forces orchestrated the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht), in which the storefronts of Jewish shops and offices were smashed and vandalized, and many synagogues were destroyed by fire.

Beginning around 1990, a spurt of growth was fueled by immigration from the former Soviet Union, so that at the turn of the 21st century, Germany had the only growing Jewish community in Europe,[9] and the majority of German Jews were Russian-speaking.

The Merovingian rulers who succeeded to the Burgundian empire were devoid of fanaticism and gave scant support to the efforts of the Church to restrict the civic and social status of the Jews.

Charlemagne (800–814) readily made use of the Roman Catholic Church for the purpose of infusing coherence into the loosely joined parts of his extensive empire, but was not by any means a blind tool of the canonical law.

From this time onward, for reasons that also apparently concerned taxes, the Jews of Germany gradually passed in increasing numbers from the authority of the emperor to that of both the lesser sovereigns and the cities.

When the Hussites made peace with the Church, the Pope sent the Franciscan friar John of Capistrano to win the renegades back into the fold and inspire them with loathing for "heresy" and "unbelief"; 41 martyrs were burned in Wrocław alone, and all Jews were forever banished from Silesia.

At this time, as once before in France, Jewish converts spread false reports in regard to the Talmud, but an advocate of the book arose in the person of Johann Reuchlin, the German humanist, who was the first one in Germany to include the Hebrew language among the humanities.

He argued, "the world results from a creative act through which the divine will seeks to realize the highest good," and accepted the existence of miracles and revelation as long as belief in God did not depend on them.

No general franchise existed, which remained a privilege for the few, who had inherited the status or acquired it when they reached a certain level of taxed income or could afford the expense of the citizen's fee (Bürgergeld).

Nevertheless, a few men came forward to promote their cause, foremost among them being Gabriel Riesser (d. 1863), a Jewish lawyer from Hamburg, who demanded full civic equality for his people.

Using their connections with Jewish businessmen to serve as military contractors, managers of mints, founders of new industries and providers to the court of precious stones and clothing, they gave economic assistance to the local rulers.

In addition, Jewish mothers put a large emphasis on proper education for their children in hopes that this would help them grow up to be more respected by their communities and eventually lead to prosperous careers.

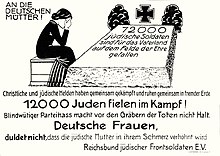

However, despite massive protests and petitions, the völkisch movement failed to persuade the government to revoke Jewish emancipation, and in the 1912 Reichstag elections, the parties with völkisch-movement sympathies suffered a temporary defeat.

While there was partially a desire for vengeance, for many Jews ensuring Russia's Jewish population was saved from a life of servitude was equally important – one German-Jewish publication stated "We are fighting to protect our holy fatherland, to rescue European culture and to liberate our brothers in the east.

[48] Under the Weimar Republic, 1919–1933, German Jews played a major role in politics and diplomacy for the first time in their history, and they strengthened their position in financial, economic, and cultural affairs.

Leading Jewish intellectuals on university faculties included physicist Albert Einstein; sociologists Karl Mannheim, Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, and Herbert Marcuse; philosophers Ernst Cassirer and Edmund Husserl; communist political theorist Arthur Rosenberg; sexologist and pioneering LGBT advocate Magnus Hirschfeld, and many others.

[69] With the majority of non-Jewish professors holding such feelings about Jews, coupled with how the Nazis' outwardly appeared in the period during and after the seizure of power, there was little motivation to oppose the anti-Jewish measures being enacted—few did, and many were actively in favor.

"[71] "German physicians were highly Nazified, compared to other professionals, in terms of party membership," observed Raul Hilberg[72] and some even carried out experiments on human beings at places like Auschwitz.

At the same time the Reich Citizenship Law was passed and was reinforced in November by a decree, stating that all Jews, even quarter- and half-Jews, were no longer citizens (Reichsbürger) of their own country.

On 4 June 1937, two young German Jews, Helmut Hirsch and Isaac Utting, were both executed for being involved in a plot to bomb the Nazi party headquarters in Nuremberg.

On 10 November 1938, Reinhard Heydrich ordered the state police and the Sturmabteilung (SA) to destroy Jewish property and arrest as many Jews as possible in what became known as the Night of Broken Glass (Kristallnacht).

Commonly referred to as "dashers and divers," the Jews lived a submerged life and experienced the struggle to find food, a relatively secure hiding space or shelter, and false identity papers while constantly evading Nazi police and strategically avoiding checkpoints.

Faster growing cities saw less persistence in antisemitic attitudes, this may be due to the fact that trade-openness was associated with more economic success and therefore higher migration rates into these regions.

The overwhelming majority of the DPs wished to emigrate to Mandatory Palestine and lived in Allied- and UNRRA-administered displaced persons camps, remaining isolated from German society.

Although the Jewish community of Germany did not have the same impact as the pre-1933 community, some Jews were prominent in German public life, including Hamburg mayor Herbert Weichmann; Schleswig-Holstein Minister of Justice (and Deputy Chief Justice of the Federal Constitutional Court) Rudolf Katz; Hesse Attorney General Fritz Bauer; former Hesse Minister of Economics Heinz-Herbert Karry; West Berlin politician Jeanette Wolff; television personalities Hugo Egon Balder, Hans Rosenthal, Ilja Richter, Inge Meysel, and Michel Friedman; Jewish communal leaders Heinz Galinski, Ignatz Bubis, Paul Spiegel, and Charlotte Knobloch (see: Central Council of Jews in Germany), film score composer Hans Zimmer, and Germany's most influential literary critic, Marcel Reich-Ranicki.

They included writers such as Anna Seghers, Stefan Heym, Stephan Hermlin, Jurek Becker, Stasi Colonel General Markus Wolf, singer Lin Jaldati, composer Hanns Eisler, and politician Gregor Gysi.

[86] According to the historian Mike Dennis, 'Already decimated by the Holocaust, East German Jewry reeled from the shock of the SED's (Socialist Unity Party of Germany) antisemitic campaigns.

[105] Germany provided several million euros to fund "nationwide programs aimed at fighting far-right extremism, including teams of traveling consultants, and victims' groups".

On 29 August 2012, in Berlin, Daniel Alter, a rabbi in visible Jewish garb, was physically attacked by a group of Arab youths, causing a head wound that required hospitalization.

[120] Through the start of the 21st century, Germany has witnessed a sizable migration of young, educated Israeli Jews seeking academic and employment opportunities, with Berlin being their favorite destination.