German war crimes

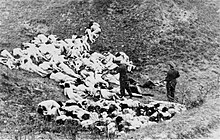

Millions of civilians and prisoners of war also died as a result of German abuses, mistreatment, and deliberate starvation policies in those two conflicts.

In August, General Lothar von Trotha of the Imperial German Army defeated the Herero in the Battle of Waterberg and drove them into the desert of Omaheke, where most of them died of thirst.

[18] Within the first two months of the war, German occupational troops killed thousands of Belgian civilians and looted and burnt scores of towns, including Leuven, which housed the country's most prominent university.

The raid was in violation of the ninth section of the 1907 Hague Convention which prohibited naval bombardments of undefended towns without warning,[20] because only Hartlepool was protected by shore batteries.

Prize rules, which were codified under the 1907 Hague Convention—such as those that required commerce raiders to warn their targets and allow time for the crew to board lifeboats—were disregarded and commercial vessels were sunk regardless of nationality, cargo, or destination.

This outraged the U.S. public, prompting the U.S. to break diplomatic relations with Germany two days later, and, along with the Zimmermann Telegram, led the U.S. entry into the war two months later on the side of the Allied Powers.

Telford Taylor (The U.S. prosecutor in the German High Command case at the Nuremberg Trials and Chief Counsel for the twelve trials before the U.S. Nuremberg Military Tribunals) explained in 1982: as far as wartime actions against enemy nationals are concerned, the [1948] Genocide Convention added virtually nothing to what was already covered (and had been since the Hague Convention of 1899) by the internationally accepted laws of land warfare, which require an occupying power to respect "family honors and rights, individual lives and private property, as well as religious convictions and liberty" of the enemy nationals.