German minority in Poland

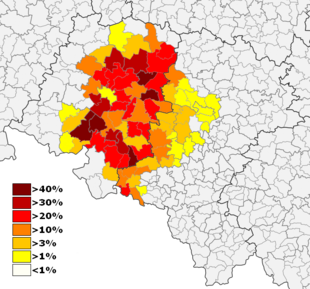

Towns with particularly high concentrations of German speakers in Opole Voivodeship include: Strzelce Opolskie; Dobrodzien; Prudnik; Głogówek; and Gogolin.

[9] German migration into areas that form part of present-day Poland began with the medieval Ostsiedlung (see also Walddeutsche in the Subcarpathian region).

Many of these Germans remained east of the Curzon line after World War I ended in 1918, including a significant number in Volhynia.

In the late 19th century, some Germans moved westward during the Ostflucht, while a Prussian Settlement Commission established others in Central Poland.

When the German occupation of Poland began, the Selbstschutz took an active part in Nazi crimes against ethnic Poles.

[11][full citation needed] Following the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, the Soviets annexed a massive portion of the eastern part of Poland (November 1939) in the wake of an August 1939 agreement between the Reich and the USSR.

After the Nazis' defeat in 1945, Poland did not regain its Soviet-annexed territory;[12] instead, Polish communists, directed by the Soviets, expelled[13] the remaining Germans who had not already been evacuated or fled[14] from the areas of Lower Silesia, Upper Silesia, Farther Pomerania, East Brandenburg, and East Prussia and made Poles take their place, some of whom were expelled from Soviet-occupied areas that had previously formed part of Poland.

[16][15] In the following years, the communists and activists inspired by the Myśl zachodnia ("Western thought") strove to "de-Germanize" and to "re-Polonize" the huge land, propagandistically termed "Recovered Territories".

[17] Since the downfall of the Polish Communist regime in 1989, the German minorities' political situation in modern-day Poland has improved, and after Poland joined the European Union in the 2004 enlargement and was incorporated into the Schengen Area, German citizens are now allowed to buy land and property in the areas where they or their ancestors used to live, and can return there if they wish.

of the ambiguity of the Polish-German minority position[clarification needed] can be seen in the life and career of Waldemar Kraft, a minister without portfolio in the West German Bundestag during the 1950s.

The Polish referred to these people using the propagandistic term “autochthonous”, as opposed to those Germans whose ancestors came to the region in the Middle Ages.

In 1951, Polish law restored equal rights to Germans in Poland in working life and in cultural and educational matters.

[23] However, the vast majority of Germans were the so-called "autochthons" who were allowed to stay in post-war Poland after declaring Polish ethnicity in a special verification process.

[26] Also, a great many of families, due to war, flight, and expulsion, had been torn apart by the border shift and now pressured the German authorities to support their relatives to leave Poland.

[23] The European policy of détente at the beginning of the 1970s, and in particular the signing of the Warsaw Treaty, ushered in the next phase of family reunions and departures of Germans, particularly the "autochthonous" population, from Poland, especially to the Federal Republic of Germany.