German retribution against Poles who helped Jews

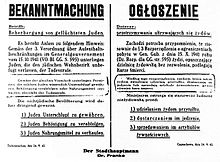

The orders of the German occupation authorities, in particular the ordinance of General Governor Hans Frank of 15 October 1941, provided for the death penalty for any Pole who gave shelter to a Jew or helped him in any other way.

[3] On that day, a meeting was held in Berlin led by SS-Gruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, attended by the chief heads of the main departments of the General Security Police Office and commander of Einsatzgruppen operating in Poland.

[2] The closing of the Lublin Ghetto initiated the mass and systematic extermination of Polish Jews living in the areas of the General Government and Białystok district, which the Germans later baptized with the cryptonym "Aktion Reinhardt".

[11] In 1941, the rapid spread of infectious diseases in overpopulated ghettos and the general radicalisation of German anti-Jewish policy resulted in tightening of the isolation restrictions imposed on Polish Jews.

[1] The third regulation on the restriction of residency in the General Government of October 15, 1941, provided for the death penalty for all Jews who "leave their designated district without authorisation", but its sentencing would be the responsibility of the German Special Courts.

[1] After the start of "Aktion Reinhardt" the German gendarmerie supported by collaborative police forces systematically tracked, captured and murdered refugees from ghettos, transports and camps.

In Warsaw, denunciators were rewarded with 500 zloty and officers of the "blue police" were promised to receive 1/3 of his cash[clarification needed] for capturing a Jew hiding "on the Aryan side".

[15] In rural areas there were gangs — usually made up of criminals, members of the social margin[clarification needed] and declared anti-Semites[1] — who tracked the fugitives and then gave them away to Germans or robbed them on their own, often committing murders and rape.

[2][6] According to Sebastian Piątkowski and Jacek A. Młynarczyk, "a milestone on the road to complete isolation of the Jewish community from the rest of the conquered population" was the signing by Hans Frank of the aforementioned Third Ordinance on Restrictions on residence in the General Government (October 15, 1941).

In all cases, these Poles are liable to the death penalty.On October 28, 1942, the Supreme Commander of SS and the Police in the General Government SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich Wilhelm Krüger (HSSPF "Ost") issued a regulation on the creation of so-called remnant ghettos in selected cities of Lublin and Warsaw districts.

At the same time, unspecified police sanctions (sicherheitspolizeiliche Maßnahmen) were announced against people who do not inform the occupation authorities about the known fact of Jewish presence outside the ghetto (in practice, this meant deportation to a concentration camp).

Moreover, in the occupied Polish lands, the Germans created a system of blackmail and dependence, obliging Poles, under the threat of the most severe punishments, to report every case of hiding Jewish fugitives to the occupation authorities.

[2][15][22] The "2014 Record of the facts of repression against Polish citizens for the help of the Jewish population during World War II" indicates that those accused of supporting Jews also received punishments such as beatings, imprisonment, exile for forced labor, deportation to a concentration camp, confiscation of property, or fines.

[23] Sebastian Piątkowski, relying on preserved documents of the special court in Radom, pointed out that especially in the case of small and disposable forms of assistance – such as providing food, clothing or money to the escapees, indicating the way, accepting correspondence – the punishment could be limited to imprisonment or exile to a concentration camp.

[8] Historians point out that Polish blackmailers and denunciators posed a very serious threat to people helping Jews, and in the Eastern Borderlands – additionally collaborators and confidants of Ukrainian, Belarusian or Lithuanian origin.

[8][12] Barbara Engelking emphasizes that due to the relatively weak saturation of rural areas with German police and gendarmerie units, many of the cases of exposing Poles hiding Jews had to be the result of reports submitted by their Polish neighbours.

Based on the findings of the investigation, Bielawski developed a brochure entitled "The crimes committed on Poles by the Nazis for their help to Jews", which in the second edition of 1987 contained the names of 872 murdered people and information about nearly 1400 anonymous victims.

[25] In 2005, the community gathered around the foundation Institute for Strategic Studies initiated a research project entitled "Index of Poles murdered and repressed for helping Jews during World War II".

As a result of these works, the Institute of National Remembrance and ISS Foundation published the "Facts of repression against Polish citizens for their help during World War II" (Warsaw 2014).

A year and a half later, the Ulmas were denounced by Włodzimierz Leś, a "blue policeman" who took possession of the Szall family's property and intended to get rid of its rightful owners.

In the winter of 1942 and 1943, the German Gendarmerie carried out a large-scale repressive action in the region of Ciepiełów, aimed at intimidating the Polish population and discouraging it from helping Jews.

In December 1942 and January 1943, the Lipsko Gendarmerie carried out three repressive actions in the colony of Boiska near Solec nad Wisłą, during which they murdered 10 people from the families of Kryczek, Krawczyk and Boryczyk and two Jews hidden in the grove of Franciszek Parol (wife of the latter was imprisoned in Radom).

The immediate cause of the repressive action was the activity of a provocateur's agent, who pretending to escape from the transport to Treblinka camp, gained information about the inhabitants of the village who helped Jews.

In his assessment:[15] The draconian rules applied on a massive scale, instead of trivialising the population, led it to bereavement and created a climate of lawlessness in which[...] hiding Jews simply became one of the many illegal activities in which people routinely risked their lives.

The principle of collective responsibility also had the opposite effect, because denunciation of the Jew brought danger to his Polish guardians, which meant a violation of the occupational order for solidarity.Other historians have estimated however that the percentage of Poles acting solely on financial grounds was only from several to twenty[11] percent.

Marcin Urynowicz points out that German terror was very effectively intimidating wide circles of Polish society, hence the real threats faced by the person to whom assistance was requested did not have a direct connection with the level of fear she felt.

[13] There are known cases where the demonstrative repressive actions carried out by the Germans, and even the threat of severe punishments themselves, have reached the goal of intimidating the local population and significantly reducing aid to Jews.

[13] According to one of the Jewish survivors the story of the massacre of the Ulma family made such a shocking impression on the local population that the bodies of 24 Jews were later found in the Markowa area, where Polish caregivers murdered them because of fear of denunciation.

[42] Stefan Korboński claimed that in Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, there was not a single case of death sentence imposed on a person helping Jewish fellow citizens.

Nevertheless, the difference between the reality of occupied Poland and the situation in Western European countries may be measured by the fact that in Holland it was possible to organise public protests against deportations of the Jewish population.