Gerolamo Cardano

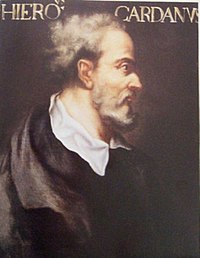

Gerolamo Cardano (Italian: [dʒeˈrɔːlamo karˈdaːno]; also Girolamo[1] or Geronimo;[2] French: Jérôme Cardan; Latin: Hieronymus Cardanus; 24 September 1501– 21 September 1576) was an Italian polymath whose interests and proficiencies ranged through those of mathematician, physician, biologist, physicist, chemist, astrologer, astronomer, philosopher, music theorist, writer, and gambler.

After a depressing childhood, with frequent illnesses, and the rough upbringing by his overbearing father, in 1520, Cardano entered the University of Pavia.

In 1525, Cardano repeatedly applied to the College of Physicians in Milan, but was not admitted owing to his combative reputation and illegitimate birth.

Having finally received his medical license, he practised mathematics and medicine simultaneously, treating a few influential patients in the process.

[11] In his exposition, he acknowledged the existence of what are now called imaginary numbers, although he did not understand their properties, described for the first time by his Italian contemporary Rafael Bombelli.

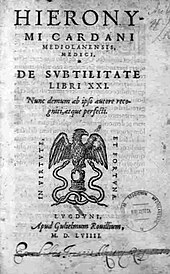

As quoted from Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology: The title of a work of Cardano's, published in 1552, De Subtilitate (corresponding to what would now be called transcendental philosophy), would lead us to expect, in the chapter on minerals, many far fetched theories characteristic of that age; but when treating of petrified shells, he decided that they clearly indicated the former sojourn of the sea upon the mountains.

[22] In 1552 Cardano travelled to Scotland with the Spanish physician William Casanatus, via London,[23] to treat the Archbishop of St Andrews who suffered of a disease that had left him speechless and was thought incurable.

The treatment was a success and the diplomat Thomas Randolph recorded that "merry tales" about Cardano's methods were still current in Edinburgh in 1562.

[25] Cardano wrote that the Archbishop had been short of breath for ten years, and after the cure was effected by his assistant, he was paid 1,400 gold crowns.

[28] The inquisitors complained about Cardano's writings on astrology, especially his claim that self-harming religiously motivated actions of martyrs and heretics were caused by the stars.

[29] In his 1543 book De Supplemento Almanach, a commentary on the astrological work Tetrabiblos by Ptolemy, Cardano had also published a horoscope of Jesus.

[30] The seventeenth-century English physician and philosopher Sir Thomas Browne possessed the ten volumes of the Lyon 1663 edition of the complete works of Cardan in his library.

[31] Browne critically viewed Cardan as: that famous Physician of Milan, a great Enquirer of Truth, but too greedy a Receiver of it.

He hath left many excellent Discourses, Medical, Natural, and Astrological; the most suspicious are those two he wrote by admonition in a dream, that is De Subtilitate & Varietate Rerum.

He is of singular use unto a prudent Reader; but unto him that only desireth Hoties,[a] or to replenish his head with varieties; like many others before related, either in the Original or confirmation, he may become no small occasion of Error.

[32] Richard Hinckley Allen tells of an amusing reference made by Samuel Butler in his book Hudibras: Cardan believ'd great states depend Upon the tip o'th' Bear's tail's end; That, as she wisk'd it t'wards the Sun, Strew'd mighty empires up and down; Which others say must needs be false, Because your true bears have no tails.

Alessandro Manzoni's novel I Promessi Sposi portrays a pedantic scholar of the obsolete, Don Ferrante, as a great admirer of Cardano.

English novelist E. M. Forster's Abinger Harvest, a 1936 volume of essays, authorial reviews and a play, provides a sympathetic treatment of Cardano in the section titled 'The Past'.

Forster believes Cardano was so absorbed in "self-analysis that he often forgot to repent of his bad temper, his stupidity, his licentiousness, and love of revenge" (212).