Gerrymandering in the United States

The term "gerrymandering" was coined after a review of Massachusetts's redistricting maps of 1812 set by Governor Elbridge Gerry noted that one of the districts looked like a mythical salamander.

When one party controls the state's legislative bodies and governor's office, it is in a strong position to gerrymander district boundaries to advantage its side and to disadvantage its political opponents.

[5] However, in early 20th century it was revealed that this theory was based on incorrect claims by Madison and his allies, and recent historical research disproved it altogether.

Historians widely believe that the Federalist newspaper editors Nathan Hale, and Benjamin and John Russell were the instigators, but the historical record does not have definitive evidence as to who created or uttered the word for the first time.

[8] Appearing with the term, and helping to spread and sustain its popularity, was a political cartoon depicting a strange animal with claws, wings and a dragon-like head satirizing the map of the odd-shaped district.

Using geographic information system and census data as input, mapmakers can use computers to process through numerous potential map configurations to achieve desired results, including partisan gerrymandering.

The shape of Mascara's newly drawn district formed a finger that stopped at his street, encompassing his house, but not the spot where he parked his car.

[21] Attorney General William P. Barr and Commerce Secretary Wilbur L. Ross Jr. have refused to cooperate with an investigation into why the Trump administration added a U.S. citizenship question to the 2020 census and specifically whether it seeks to benefit Republicans as suggested by Hofeller's study.

[25] The Supreme Court had ruled in Davis v. Bandemer (1986) that partisan gerrymandering violates the Equal Protection Clause and is a justiciable matter.

Writing for a plurality of the Court, Justice White said that partisan gerrymandering occurred when a redistricting plan was enacted with both the intent and the effect of discriminating against an identifiable political group.

Justices Powell and Stevens said that partisan gerrymandering should be identified based on multiple factors, such as electoral district shape and adherence to local government boundaries.

[30] Opinions from Vieth and League, as well as the strong Republican advantage created by its REDMAP program, had led to a number of political scholars working alongside courts to develop such a method to determine if a district map was a justiciable partisan gerrymandering, as to prepare for the 2020 elections.

[45] Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benisek were decided on June 27, 2019, which, in the 5–4 decision, determined that judging partisan gerrymandering cases is outside of the remit of the federal court system due to the political questions involved.

[49] In October 2019, a three-judge panel in North Carolina threw out a gerrymandered electoral map with its decision in the case of Harper v. Hall, citing violation of the constitution to disadvantage the Democratic Party.

With the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and its subsequent amendments, redistricting to carve maps to intentionally diminish the power of voters who were in a racial or linguistic minority, was prohibited.

"[58] On October 3, 2022, the Supreme Court heard arguments in Merril v. Milligan[59] to conclude whether or not Alabama is obligated to create a second Black-majority congressional district under the Voting rights Act of 1965.

This is because of packing people of color into the 7th district to then separate the rest of the Black electorate into six white-majority states, diluting their ability to impact elections.

While the Equal Protection Clause, along with Section 2 and Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, prohibit jurisdictions from gerrymandering electoral districts to dilute the votes of racial groups, the Supreme Court has held that in some instances, the Equal Protection Clause prevents jurisdictions from drawing district lines to favor racial groups.

The Supreme Court first recognized these "affirmative racial gerrymandering" claims in Shaw v. Reno (Shaw I) (1993),[60] holding that plaintiffs "may state a claim by alleging that [redistricting] legislation, though race neutral on its face, rationally cannot be understood as anything other than an effort to separate voters into different districts on the basis of race, and that the separation lacks sufficient justification".

In United States v. Hays (1995),[63] the Supreme Court held that only those persons who reside in a challenged district may bring a racial gerrymandering claim.

[61]: 623 [63]: 743–744 In Miller v. Johnson (1995),[64] the Supreme Court held that a redistricting plan must be subjected to strict scrutiny if the jurisdiction used race as the "predominant factor" in determining how to draw district lines.

When the state legislature considered representation for Arizona's Native American reservations, they thought each needed their own House member, because of historic conflicts between the Hopi and Navajo nations.

It ensured that a common community of interest will be represented, rather than having portions of the coastal areas be split up into districts extending into the interior, with domination by inland concerns.

In his dissenting opinion in LULAC v. Perry, Justice John Paul Stevens, joined by Justice Stephen Breyer, quoted Bill Ratliffe, former Texas lieutenant governor and member of the Texas state senate saying, "political gain for the Republicans was 110% the motivation for the plan," and argued that a plan whose "sole intent" was partisan could violate the Equal Protection Clause.

One extreme example is Waupun, Wisconsin, where two city council districts are made up of 61% and 76% incarcerated people, but as of 2019, neither elected representative has visited the local prisons.

States that made similar orders in time for the 2020 census include California (2011), Delaware (2010), Nevada (2019), Washington (2019), New Jersey (2020), Colorado (2020),[77] Virginia (2020) and Connecticut (2021), Montana (2023) and Minnesota (2024).

[26]: 1058 [83]: 540 In the Supreme Court case of Karcher v. Daggett (1983),[84] a New Jersey redistricting plan was overturned when it was found to be unconstitutional by violating the constitutional principle of one person, one vote.

It suggested that partisan gerrymandering can often lead to adverse health complications for minority populations that live closer to United States superfund sites and additionally found that during redistricting periods, minority populations are "effectively gerrymandered out" of districts that tend to have fewer people of color in them and are farther away from toxic waste sites.

This redistricting can be seen as a deliberate move to further marginalize minority populations and restrict them from gaining access to congressional representation and potentially fixing environmental hazards in their communities.

Enten points to studies which find that factors other than gerrymandering account for over 75% of the increase in polarization in the past forty years, presumably due largely to changes among voters themselves.

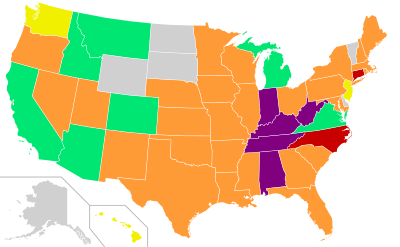

State legislatures control redistricting

Commissions control redistricting

Nonpartisan staff develop the maps, which are then voted on by the state legislature

No federal redistricting due to having only one congressional district