Gestapo

The power of the Gestapo was used to focus upon political opponents, ideological dissenters (clergy and religious organisations), career criminals, the Sinti and Roma population, handicapped persons, homosexuals, and, above all, the Jews.

[5] Contrary to popular perception, the Gestapo was actually a relatively small organization with limited surveillance capability; still it proved extremely effective due to the willingness of ordinary Germans to report on fellow citizens.

[8][9] He originally wanted to name it the Secret Police Office (Geheimes Polizeiamt), but the German initials, "GPA", were too similar to those of the Soviet State Political Directorate (Gosudarstvennoye Politicheskoye Upravlenie, or GPU).

[16] Many of the Gestapo employees in the newly established offices were young and highly educated in a wide variety of academic fields and moreover, represented a new generation of National Socialist adherents, who were hard-working, efficient, and prepared to carry the Nazi state forward through the persecution of their political opponents.

[21] Several Nazi chieftains, among them Göring, Joseph Goebbels, Rudolf Hess, and Himmler, began a concerted campaign to convince Hitler to take action against Röhm.

As late as 6 June 1944, Heinrich Müller—concerned about the leakage of information to the Allies—set up a special unit called Sonderkommando Jerzy that was meant to root out the Polish intelligence network in western and southwestern Europe.

[45][46][a] Early in the regime's existence, harsh measures were meted out to political opponents and those who resisted Nazi doctrine, such as members of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD); a role originally performed by the SA until the SD and Gestapo undermined their influence and took control of Reich security.

[47] Because the Gestapo seemed omniscient and omnipotent, the atmosphere of fear they created led to an overestimation of their reach and strength; a faulty assessment which hampered the operational effectiveness of underground resistance organisations.

[51] Meanwhile, the SA and police occupied trade union headquarters, arrested functionaries, confiscated their property and assets; all by design so as to be replaced on 12 May by the German Labour Front (DAF), a Nazi organisation placed under the leadership of Robert Ley.

[51] Many parts of Germany (where religious dissent existed upon the Nazi seizure of power) saw a rapid transformation; a change as noted by the Gestapo in conservative towns such as Würzburg, where people acquiesced to the regime either through accommodation, collaboration, or simple compliance.

When Church leaders (clergy) voiced their misgiving about the euthanasia program and Nazi racial policies, Hitler intimated that he considered them "traitors to the people" and went so far as to call them "the destroyers of Germany".

[55] The extreme anti-semitism and neo-pagan heresies of the Nazis caused some Christians to outright resist,[56] and Pope Pius XI to issue the encyclical Mit brennender Sorge denouncing Nazism and warning Catholics against joining or supporting the Party.

After Heydrich (who was staunchly anti-Catholic and anti-Christian) was assassinated in Prague, his successor, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, relaxed some of the policies and then disbanded Department IVB (religious opponents) of the Gestapo.

This was partly because of the Venlo incident of 9 November 1939,[77] in which SD and Gestapo agents, posing as anti-Nazis in the Netherlands, kidnapped two British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) officers after having lured them to a meeting to discuss peace terms.

One of the more famous schemes, Operation Valkyrie, involved a number of senior German officers and was carried out by Colonel Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg.

[88] Describing the activities of the organisation, Göring boasted about the utter ruthlessness required for Germany's recovery, the establishment of concentration camps for that purpose, and even went on to claim that excesses were committed in the beginning, recounting how beatings took place here and there.

[89] On 26 April 1933, he reorganised the force's Amt III as the Gestapa (better-known by the "sobriquet" Gestapo),[90] a secret state police intended to serve the Nazi cause.

Himmler's subsequent appointment to Chef der Deutschen Polizei (Chief of German Police) and status as Reichsführer-SS made him independent of Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick's nominal control.

In lieu of naming convention changes, the original construct of the SiPo, Gestapo, and Kripo cannot be fully comprehended as "discrete entities", since they ultimately formed "a conglomerate in which each was wedded to each other and the SS through its Security Service, the SD".

[101] It was the Gestapo chief, SS-Brigadierführer Heinrich Müller, who kept Hitler abreast of the killing operations in the Soviet Union and who issued orders to the four Einsatzgruppen that their continual work in the east was to be "presented to the Führer.

Employing biological metaphors, Best emphasised a doctrine which encouraged members of the Gestapo to view themselves as 'doctors' to the 'national body' in the struggle against "pathogens" and "diseases"; among the implied sicknesses were "communists, Freemasons, and the churches—and above and behind all these stood the Jews".

[109] Heydrich thought along similar lines and advocated both defensive and offensive measures on the part of the Gestapo, so as to prevent any subversion or destruction of the National Socialist body.

Historian George C. Browder contends that there was a four-part process (authorisation, bolstering, routinisation, and dehumanisation) in effect, which legitimised the psycho-social atmosphere conditioning members of the Gestapo to radicalised violence.

[115] In lower Franconia, which included Würzburg, there were only twenty-two Gestapo officers overseeing 840,000 or more inhabitants; this meant that the Nazi secret police "was reliant on Germans spying on each other".

[4] "Selective terror" by the Gestapo, as mentioned by Johnson, is also supported by historian Richard Evans who states that, "Violence and intimidation rarely touched the lives of most ordinary Germans.

[141] Much like their affiliated organisations, the SS and the SD, the Gestapo "played a leading part" in enslaving and deporting workers from occupied territory, torturing and executing civilians, singling out and murdering Jews, and subjecting Allied prisoners of war to terrible treatment.

"[143] Once the German armies advanced into enemy territory, they were accompanied by Einsatzgruppen staffed by officers from the Gestapo and Kripo, who usually operated in the rear areas to administer and police the occupied land.

[150] While in many countries the Nazis occupied in the East, the local domestic police forces supplemented German operations, noted Holocaust historian, Raul Hilberg, asserts that "those of Poland were least involved in anti-Jewish actions.

[151] In places like Denmark, there were some 550 uniformed Danes in Copenhagen working with the Gestapo, patrolling and terrorising the local population at the behest of their German overseers, many of whom were arrested after the war.

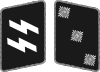

[159] These groups—the Nazi Party and government leadership, the German General staff and High Command (OKW); the Sturmabteilung (SA); the Schutzstaffel (SS), including the Sicherheitsdienst (SD); and the Gestapo—had an aggregate membership exceeding two million, making a large number of their members liable to trial when the organisations were convicted.