Gezer

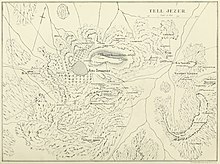

The archaeological site of Tel Gezer rises to an elevation of 229 metres (751 ft) above sea-level, and affords a commanding prospect of the plains to the west, north and east.

Later, In the modern era, Tel Gezer was the site of the Palestinian village of Abu Shusheh, the residents of which fled[1] or were expelled by Israeli forces during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.

[5]According to the Hebrew Bible, the only source for this particular event, the Sack of Gezer took place at the beginning of the 10th century BCE,[6] when the city was conquered and burned by an unnamed Egyptian pharaoh, identified by some with Siamun, during his military campaign in Philistia.

[7] Professor Edward Lipinski argues that Gezer, then unfortified, was destroyed late in the 10th century (and thus not contemporary with Solomon) and that the most likely Pharaoh was Shoshenq I (ruled 943–922 BCE).

[10] One fragmentary but well-known surviving triumphal relief scene from the Temple of Amun at Tanis believed to be related to the sack of Gezer depicts an Egyptian pharaoh smiting his enemies with a mace.

Alternatively, Paul S. Ash had put forward a detailed argument that Siamun's relief portrays a fictitious battle.

Verification of the identification of this site with biblical Gezer comes from a dozen bilingual inscriptions in either Hebrew or Aramaic, and Greek, found engraved on rocks several hundred meters from the tell.

Today's archaeological site spans an area of 130 dunams (32 acres), and contains 26 levels of settlement, from the Chalcolithic to the early Roman periods (3500 BCE to 100 CE).

[16] The first settlement established at Tel Gezer dates to the end of the 4th millennium BCE during the Chalcolithic period, when large caves cut into the rock were used as dwellings.

[17] In the Middle Bronze Age IIB (MBIIB, first half of the 2nd millennium BCE), Gezer became a major city, well fortified[6] and containing a large cultic site.

[20] In what remained of the outer rampart, it reached a height of about 5 metres, and was built of compacted alternating layers of chalk and earth covered with plaster.

[19][20] The city gate stood near the southwest corner of the wall, was flanked by two towers which protected the wooden doors, a common design for its time.

[22] The tell was surrounded by a massive stone wall and towers, protected by a five-meter-high (16 ft) earthen rampart covered with plaster.

1600 BCE, each masseba possibly representing a Canaanite city connected to Gezer by treaties enforced by rituals performed here.

[citation needed] In the Late Bronze Age (second half of the 2nd millennium BCE) a new city wall, 4 m (13 ft) thick, was erected outside the earlier one.

[20] It is a very rare example of Late Bronze Age fortifications in the country, witness for the elevated political status of Gezer in southern Canaan during Egyptian rule.

[citation needed] The Canaanite city was destroyed in a fire, presumably in the wake of a campaign by the Egyptian pharaoh Thutmose III (ruled 1479–1425 BCE).

[6] Discoveries of several pottery vessels, a cache of cylinder seals and a large scarab with the cartouche of Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III attest to the existence of a city at Gezer's location in the 14th century BCE—one that was apparently destroyed in the next century[30]—and suggest that the city was inhabited by Canaanites with strong ties to Egypt.

[42] At any rate, a fiery destruction so severe befell the city at this time, insofar that it reduced the upper two courses of stone in the inner casemate wall to powdery lime.

Elsewhere, Josephus (Jewish War 1.170) wrote that a certain "Gadara" (Greek: Γαδάροις) was one of the five synedria, or regional administrative capitals of the Hasmonean realm, established by Aulus Gabinius, the Roman proconsul of Syria, in 57 BCE.

Their acquisition of these lands would prove "a fortunate circumstance" for the excavator, as the site was later put at the disposal of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

[57][58] In 2011 professor Dennis Cole, archaeologist Dan Warner and engineer Jim Parker from NOBTS, and Tsvika Tsuk from the Israeli Parks Authority, led another team in an attempt to finish the effort.

There are only a few "lost" biblical cities that have been positively identified through inscriptions discovered by means of archaeological work (surveys or digs).

[61] Analysis of the lettering have led to the conclusion that they were all contemporaneous, with opinions based on palaeography and history slightly diverging in regard to their date – either Hasmonean or Herodian.

[61] The earlier date and the Hebrew script can be connected to what is known from the First Book of Maccabees about Simon replacing the gentile inhabitants with Jewish ones (1 Macc.

[61] Other scholars are not convinced that the language of the inscriptions is Hebrew and not Aramaic, leaving both options as possible as is the case in the Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae.

[62] In July 2017, archaeologists discovered skeletal remains of a family of three, one of the adults and a child wearing earrings, believed to have been killed during an Egyptian invasion in the 13th century BCE.

Results were not published due the Weill's assistant Paule Zerlwer-Silberberg dying in a camp in occupied France and the excavation data was lost at that time.

Wright, William Dever and Joe Seger worked at Gezer on behalf of the Nelson Glueck School of Archaeology in the Hebrew Union College and Harvard University.

[76] Excavations were renewed in June 2006 by a consortium of institutions under the direction of Steve Ortiz of the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (SWBTS) and Sam Wolff of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).