Giant squid

It is usually found near continental and island slopes from the North Atlantic Ocean, especially Newfoundland, Norway, the northern British Isles, Spain and the oceanic islands of the Azores and Madeira, to the South Atlantic around southern Africa, the North Pacific around Japan, and the southwestern Pacific around New Zealand and Australia.

The vertical distribution of giant squid is incompletely known, but data from trawled specimens and sperm whale diving behavior suggest it spans a large range of depths, possibly 300–1,000 metres (980–3,280 ft).

[citation needed] The inside surfaces of the arms and tentacles are lined with hundreds of subspherical suction cups, 2 to 5 cm (3⁄4 to 2 in) in diameter, each mounted on a stalk.

The giant squid probably cannot see color, but it can probably discern small differences in tone, which is important in the low-light conditions of the deep ocean.

[citation needed] Like all cephalopods, giant squid use organs called statocysts to sense their orientation and motion in water.

Much of what is known about giant squid age is based on estimates of the growth rings and from undigested beaks found in the stomachs of sperm whales.

[3] Based on the examination of 130 specimens and of beaks found inside sperm whales, giant squids' mantles are not known to exceed 2.25 m (7 ft 4.6 in).

[25] In males, as with most other cephalopods, the single, posterior testis produces sperm that move into a complex system of glands that manufacture the spermatophores.

The intact nature of the specimen indicates that the giant squid managed to escape its rival by slowly retreating to shallow water, where it died of its wounds.

[45] Pliny the Elder, living in the first century AD, also described a gigantic squid in his Natural History, with the head "as big as a cask", arms 30 ft (9.1 m) long, and carcass weighing 700 lb (320 kg).

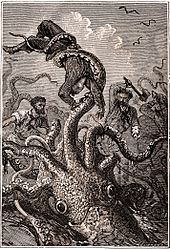

[46]: 11 [47][48] Tales of giant squid have been common among mariners since ancient times, and may have led to the Norse legend of the kraken,[49] a tentacled sea monster as large as an island capable of engulfing and sinking any ship.

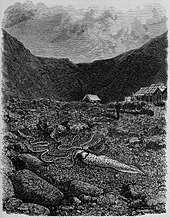

A portion of a giant squid was secured by the French corvette Alecton in 1861, leading to wider recognition of the genus in the scientific community.

[57] The Museo del Calamar Gigante in Luarca, Spain, had by far the largest collection on public display, but many of the museum's specimens were destroyed during a storm in February 2014.

The larvae closely resemble those of Nototodarus and Onykia, but are distinguished by the shape of the mantle attachment to the head, the tentacle suckers, and the beaks.

[citation needed] By the turn of the 21st century, the giant squid remained one of the few extant megafauna to have never been photographed alive, either in the wild or in captivity.

[59][46]: 211 In 1993, an image purporting to show a diver with a live giant squid (identified as Architeuthis dux) was published in the book European Seashells.

[61] The first image of a live mature giant squid was taken on 15 January 2002, on Goshiki beach, Amino Cho, Kyoto Prefecture, Japan.

The first photographs of a live giant squid in its natural habitat were taken on 30 September 2004, by Tsunemi Kubodera (National Science Museum of Japan) and Kyoichi Mori (Ogasawara Whale Watching Association).

The images were created on their third trip to a known sperm whale hunting ground 970 km (600 mi) south of Tokyo, where they had dropped a 900 m (3,000 ft) line baited with squid and shrimp.

The photo sequence, taken at a depth of 900 metres (3,000 ft) off Japan's Ogasawara Islands, shows the squid homing in on the baited line and enveloping it in "a ball of tentacles".

In November 2006, American explorer and diver Scott Cassell led an expedition to the Gulf of California with the aim of filming a giant squid in its natural habitat.

The team employed a novel filming method: using a Humboldt squid carrying a specially designed camera clipped to its fin.

[69][better source needed] In July 2012, a crew from television networks NHK and Discovery Channel captured what was described as "the first-ever footage of a live giant squid in its natural habitat".

[75] To capture the footage the team aboard OceanX's vessel MV Alucia traveled to the Ogasawara Islands, south of Tokyo and utilized the ship's crewed submersibles.

It was drawn into viewing range by both artificial bioluminescence created to mimic panicking Atolla jellyfish and by using a Thysanoteuthis rhombus (diamond squid) as bait.

[78] On 19 June 2019, in an expedition run by the National Oceanic & Atmospheric Association (NOAA),[79] known as the Journey to Midnight, biologists Nathan J. Robinson and Edith Widder captured a video of a juvenile giant squid at a depth of 759 meters (2,490 feet) in the Gulf of Mexico.

Michael Vecchione, a NOAA Fisheries zoologist, confirmed that the captured footage was that of the genus Architeuthis, and that the individual filmed measured at somewhere between 10 and 12 ft (3.0 and 3.7 m).

[80] Videos of live giant squids have been occasionally captured near the surface since the 2012 sighting, with one of these aforementioned individuals being guided back into the open ocean after appearing in Toyama Harbor on 24 December 2015.

In 2022, a live specimen was found off the coast of Japan, and an attempt was made to transport it to the Echizen Matsushima Aquarium in the city of Sakai.

[85] Representations of the giant squid have been known from early legends of the kraken through books such as Moby-Dick and Jules Verne's 1870 novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas on to other novels such as Ian Fleming's Dr. No, Peter Benchley's Beast (adapted as a film called The Beast), and Michael Crichton's Sphere (adapted as a film).