Giants of Mont'e Prama

[3] Along with the statues, other sculptures recovered at the site include large models of nuraghe buildings and several baetyl sacred stones of the "oragiana" type, used by Nuragic Sardinians in the making of "giants' graves".

[18] Investigations carried out after the fortuitous discovery of a prehistoric altar at Monte d'Accoddi (Sassari), have revealed that – alongside the production of geometric figurines – the great statuary was already present at that time in Sardinia, given that at the "temple of Accoddi" several stelae and menhirs were recovered.

[11][20] After the spreading of Bonnanaro culture on the island, the tradition of the statue-stelae seems to die out, while it continues until 1200 BC with the Nuragic-related Torrean civilization facies of Corsica, featuring warriors represented in the Filitosa sculptures.

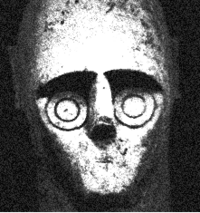

[23] In a successive evolution stage, the relief technique was employed in Sardinia – for the first time after Eneolithic sculptures – to represent a human face, as shown in the famous baetyl of "San Pietro di Golgo" (Baunei).

[29][30] According to the archaeologist Fulvia Lo Schiavo, the sculptures of northern Sardinia testify the existence of a Nuragic proto-statuary, an intermediate step of an evolutionary process that from the "eyed baetyls" of the "Oragiana type", would eventually lead to the anthropomorphic statues of Mont'e Prama.

In fact, within the Nuragic civilization craftsmen able to perform perfect stonework were certainly at hand, as demonstrated by the refined sacred wells and giant's graves built in the isodomic technique.

[33] The ability in handling stones and the spread of sculpture in the round throughout Nuragic Sardinia, is also attested by the nuraghe models mentioned above and by sculpted protomes found in several sacred wells.

[34][35] Given the location of the numerous fragments at Mont'e Prama and of the unique one at Narbolia, it is speculated that the statues were originally erected near the necropolis itself or in a still unidentified place within the Sinis Peninsula, a region extending north from the Gulf of Oristano, between the Sea of Sardinia and the pond of Cabras.

The theologian and writer, Salvatore Vidal, speaking of the Sinis Peninsula in his Clypeus Aureus excellentiae calaritanae (1641), reports the toponym Montigu de Prama.

The Franciscan friar Antonio Felice Mattei, who in the eighteenth century wrote a historiography of Sardinian dioceses and bishops, mentions Montigu Palma as one of the localities within the Sinis peninsula.

Textual evidence from cuneiform and reliefs of the New Kingdom of Egypt relate that Sea Peoples were the final catalyst that put into motion the fall of Aegean civilizations and Levantines states.

However, the Shardana are listed – in Papyrus Wilbour – as living in Middle Egypt during the time of Ramesses V, which would suggest that at least some of them were settled in Egypt.Between the twelfth and ninth centuries BC, Sardinia appears to be connected to Canaan, Syria, and Cyprus by at least four cultural currents: the first two are the most ancient, they can be defined as Syrian and Philistine, and are exquisitely commercial in character.

Presently (2012), the mortuary complex can be divided into two main areas: the first one, parallelepiped-shaped, was investigated by the archaeologist Alessandro Bedini in 1975; the second one is serpentine-shaped and has been excavated between 1976 and 1979, by Maria Ferrarese Ceruti and Carlo Tronchetti.

This so-called "Bedini's area" appears to have undergone three phases of development: In the section excavated by Carlo Tronchetti, the beginning (spatial and chronological) of the necropolis is marked by a slabstone standing upright, juxtaposed with the first tomb at the southern side.

The layout of the complex recalls in fact the plan of a giant grave, and this suggestion is reinforced by the presence of baetyls, a feature typical of the ancient Bronze Age Sardinian tombs.

According to the account of the two finders, Sisinnio Poddi and Battista Meli, the finding took place by chance in March 1974, while they were preparing the sowing of two adjacent lots that they rented yearly from the "Confraternity of Santo Rosario" of Cabras.

[65] At the beginning of every sowing season the two finders noticed that the fragments of the previous year had considerably diminished, because they were removed from people aware of their historical value or employed as building material.

Most of the sculptures at the Center for Restoration and Conservation of Li Punti (Sassari) are missing their heads and the cause lies in the fact that the site was unattended and was plundered for a long time.

[68] It is difficult to find parallels for these sculptures in the Mediterranean area: Boxer is the conventional term referring to a category of Nuragic bronze statuettes, furnished with a weapon similar to the cestus, that wraps the forearm with a rigid sheath, probably metallic.

The different fragments of upper limbs often show the left arm furnished with a brassard holding a bow, while the right hand is extended forward like in the typical gesture of salutation commonly seen in Sardinian bronze statuettes.

[87] These big sculptures are modular, and unlike the remaining nuraghe models from Sardinia, in that the shaft of the mast tower is joined to the top part through an inter-space, whose pivot and binder is constituted by a core of lead.

The stone brackets and their function have been depicted by means of parallel incised lines or grooves and the blocks – abundantly found in archaeological sites after the collapse of top parts – confirm the perfect matching of these models with the Nuragic architecture of Middle and Recent Bronze Age.

Previously the chronological data was provided by the stratigraphic excavation (in some limited areas), by the stylistic comparison with the bronze statuettes, as well as by the indications of various finds (pottery, scarab, and fibula).

In this regard there are two opposing trends of thought: In any case – according to the archaeologist Marco Rendelli – the close stylistic relationship between the bronze statuettes and the statues of Mont'e Prama proves that the two forms of art must be, at least partially, contemporaneous.

[136] The archaeologist Giovanni Ugas, while recognizing the beginning of this vascular production in the Final Bronze, considers it preferable to date the artifacts of Mont'e Prama to the Iron Age.

[137] For both the archaeologists Giovanni Ugas and Vincenzo Santoni the ceramics of Mont'e Prama find precise comparison in the Nuragic clay finds found at the Lipari castle, a site already frequented by the Nuragics during the so-called Ausonio I in the Recent Bronze but which, but which, regarding the vascular forms, present more precise comparisons with the site of Mont’e Prama in the phase of the so-called Ausonio II of the Final Bronze.

[35] Nuraghe models found together with the statues can be seen both as sacred symbols and as a claim for Nuragic identity: Despite a general consensus about values and ideologies underlying the monumental complex of Mont'e Prama, political implications and artistic influences are still hotly debated.

[158] Furthermore, the geometric "Abini-Teti style", rules out a possible placement of the statues within the orientalizing culture and period, only appearing in bronze artifacts of the seventh century BC.

At the site, a surface survey among the stones piled from a field tillage uncovered a head carved in sandstone, surmounted by a tall and bent headgear, embellished with tusks.

Other fragments from the same site seem to belong to a human trunk with a cross belt, with a clear image of a small palm tree, sculpted in relief and partially painted in red.