Sardinian language

Following the end of the Roman Empire in Western Europe, Sardinia passed through periods of successive control by the Vandals, Byzantines, local Judicates, the Kingdom of Aragon, the Savoyard state, and finally Italy.

[25][26][27][28][29][30] Although the Sardinian-speaking community can be said to share "a high level of linguistic awareness",[31] policies eventually fostering language loss and assimilation have considerably affected Sardinian, whose actual speakers have become noticeably reduced in numbers over the last century.

[49] Although its lexical base is mostly of Latin origin, Sardinian nonetheless retains a number of traces of the linguistic substratum predating the Roman conquest of the island: several words and especially toponyms stem from Paleo-Sardinian[50] and, to a lesser extent, Phoenician-Punic.

[51][52][53] In addition to the aforementioned substratum, linguists such as Max Leopold Wagner and Benvenuto Aronne Terracini trace much of the distinctive Latin character of Sardinia to the languoids once spoken by the Christian and Jewish Berbers in North Africa, known as African Romance.

It did not take long before they started gravitating around the Carthaginian sphere of influence, whose level of prosperity spurred Carthage to send a series of expeditionary forces to the island; although they were initially repelled by the natives, the North African city vigorously pursued a policy of active imperialism and, by the sixth century, managed to establish its political hegemony and military control over South-Western Sardinia.

Although the colonists and negotiatores (businessmen) of strictly Italic descent would later play a relevant role in introducing and spreading Latin to Sardinia, Romanisation proved slow to take hold among the Sardinian natives,[94] whose proximity to the Carthaginian cultural influence was noted by Roman authors.

Casula is convinced that the Vandal domination caused a "clear breaking with the Roman-Latin writing tradition or, at the very least, an appreciable bottleneck" so that the subsequent Byzantine government was able to establish "its own operational institutions" in a "territory disputed between the Greek- and the Latin-speaking world".

[113] Michele Amari, quoted by Pinelli, writes that "the attempts of the Muslims of Africa to conquer Sardinia and Corsica were frustrated by the unconquered valour of the poor and valiant inhabitants of those islands, who saved themselves for two centuries from the yoke of the Arabs".

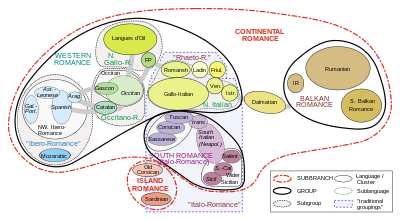

[120] Sardinian was the first Romance language of all to gain official status, being used by the four Judicates,[121][122][123][124][note 3] former Byzantine districts that became independent political entities after the Arab expansion in the Mediterranean had cut off any ties left between the island and Byzantium.

[134][135] According to Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, it was in the wake of the fall of the Judicates of Cagliari and Gallura, in the second half of the 13th century, that Sardinian began to fragment into its modern dialects, undergoing some Tuscanization under the rule of the Republic of Pisa;[136] it did not take long before the Genoese too started carving their own sphere of influence in northern Sardinia, both through the mixed Sardinian-Genoese nobility of Sassari and the members of the Doria family.

[163] Other documents are the 1080 "Logudorese Privilege", the 1089 Torchitorius' Donation (in the Marseille archives), the 1190–1206 Marsellaise Chart (in Campidanese Sardinian) and an 1173 communication between the Bishop Bernardo of Civita and Benedetto, who oversaw the Opera del Duomo in Pisa.

[165] The war had, among its motives, a never dormant and ancient Arborean political design to establish "a great island nation-state, wholly indigenous" which was assisted by the massive participation of the rest of the Sardinians, i.e. those not residing within the jurisdiction of Arborea (Sardus de foras),[166] as well as a widespread impatience with the foreign importation of a feudal regime, specifically "more Italie" and "Cathalonie", which threatened the survival of deep-rooted indigenous institutions and, far from ensuring the return of the island to a unitary regime, had only introduced there "tot reges quot sunt ville" ('as many petty rulers as there are villages'),[167] whereas instead "Sardi unum regem se habuisse credebant" ('the Sardinians believed they had one single king').

The conflict between the two sovereign and warring parties, during which the Aragonese possessions making up the Kingdom of Sardinia were first administratively split into two separate "halves" (capita) by Peter IV the Ceremonious in 1355, ended after sixty-seven years with the Iberian victory at Sanluri in 1409 and the renunciation of any succession right signed by William II of Narbonne in 1420.

Despite Catalan being widely spoken and written on the island at this time, leaving a lasting influence in Sardinia, Sardinian continued to be used in documents pertaining to the Kingdom's administrative and ecclesiastical spheres until the late 17th century.

[187][176] Cristòfor Despuig, in Los Colloquis de la Insigne Ciutat de Tortosa, had previously claimed in 1557 that, although Catalan had carved out a place for itself as llengua cortesana, in many parts of the island the "ancient language of the Kingdom" ("llengua antigua del Regne") was still preserved;[188] the ambassador and visitador reial Martin Carillo (supposed author of the ironic judgment on the Sardinians' tribal and sectarian divisions: "pocos, locos, y mal unidos" 'few, thickheaded, and badly united'[189]) noted in 1611 that the main cities spoke Catalan and Spanish, but outside these cities no other language was understood than Sardinian, which in turn was understood by everyone in the entire Kingdom;[188] Joan Gaspar Roig i Jalpí, author of Llibre dels feyts d'armes de Catalunya, reported in the mid-seventeenth century that in Sardinia "parlen la llengua catalana molt polidament, axì com fos a Catalunya" ('they speak Catalan very well, as though I was in Catalonia');[188] Anselm Adorno, originally from Genoa but living in Bruges, noted in his pilgrimages how, many foreigners notwithstanding, the natives still spoke their own language (linguam propriam sardiniscam loquentes);[190]); another testimony is offered by the rector of the Jesuit college of Sassari Baldassarre Pinyes who, in Rome, wrote: "As far as the Sardinian language is concerned, Your Paternity should know that it is not spoken in this city, nor in Alghero, nor in Cagliari: it is only spoken in the towns".

The Savoyard representative, the Count of Lucerna di Campiglione, received the definitive deed of cession from the Austrian delegate Don Giuseppe dei Medici, on condition that the "rights, statutes, privileges of the nation" that had been the subject of diplomatic negotiations were preserved.

[213][214][215] Given the current situation, the Piedmontese ruling class which held the reins of the island, in this early phase, resolved to maintain its political and social institutions, while at the same time progressively hollowing them out[216] as well as "treating the [Sardinian] followers of one faction and of the other equally, but keeping them divided in such a way as to prevent them from uniting, and for us to put to good use such rivalry when the occasion presents itself".

[218] In fact, since imposing Italian would have violated one of the fundamental laws of the Kingdom, which the new rulers swore to observe upon taking on the mantle of King, Victor Amadeus II emphasised the need for the operation to be carried out through incremental steps, small enough to go relatively unnoticed (insensibilmente), as early as 1721.

The most famous literary product born out of such political unrest was the poem Su patriottu sardu a sos feudatarios, noted as a testament of the French-inspired democratic and patriotic values, as well as Sardinia's situation under feudalism.

[314] While the interior managed to at least partially resist this intrusion at first, everywhere else the regime had succeeded in thoroughly supplanting the local cultural models with new ones hitherto foreign to the community and compress the former into a "pure matter of folklore", marking a severance from the island's heritage that engendered, according to Guido Melis, "an identity crisis with worrying social repercussions", as well as "a rift that could no longer be healed through the generations".

[382] The first scientific work in Sardinian (Sa chistione mundiali de s'Energhia), delving into the question of modern energy supplies, was written by Paolo Giuseppe Mura, Physics Professor at the University of Cagliari, in 1995.

[387] Nevertheless, the law proved to be a positive step towards the legalization of Sardinian as it put at least an end to the ban on the language which had been in effect since the Italian Unification,[388] and was deemed as a starting point, albeit timid, to pursue a more decentralized school curriculum for the island.

[394][395] Similar issues of identity have been observed in regard to the community's attitude toward what they positively perceive to be part of "modernity", generally associated with the Italian cultural sphere, as opposed to the Sardinian one, whose aspects have long been stigmatized as "primitive" and "barbarous" by the political and social institutions that ruled the island.

[398] A number of other factors like a considerable immigration flow from mainland Italy, the interior rural exodus to urban areas, where Sardinian is spoken by a much lower percentage of the population,[note 16] and the use of Italian as a prerequisite for jobs and social advancement actually hinder any policy set up to promote the language.

[430][431][432][433] It is also possible to switch to Sardinian even in Telegram[434][435] and a number of other programs, like F-Droid, Diaspora, OsmAnd, Notepad++, QGIS, Swiftkey, Stellarium,[436] Skype,[437] VLC media player for Android and iOS, Linux Mint Debian Edition 2 "Betsy", Firefox[438][439] etc.

Roberto Bolognesi argues that, in the face of the persistent denial and rejection of the Sardinian language, it is as if the latter "had taken revenge" on its original community of speakers "and continues to do so by "polluting" the hegemonic linguistic system", recalling Gramsci's prophetic warning uttered at the dawn of the previous century.

[505] Still, arrangements for bilingualism exist only on paper[506] and factors such as the intergenerational transmission, which remain essential in the reproduction of the ethnolinguistic group, are severely compromised because of Italianisation;[507] many young speakers, who have been raised in Italian rather than Sardinian, have a command of their ethnic language which does not extend beyond a few stereotyped formulas.

The people appointed for the task were Eduardo Blasco Ferrer, Roberto Bolognesi, Diego Salvatore Corraine, Ignazio Delogu, Antonietta Dettori, Giulio Paulis, Massimo Pittau, Tonino Rubattu, Leonardo Sole, Heinz Jürgen Wolf, and Matteo Porru acting as the Committee's secretary.

The new experimental standard proposal, published in 2006, was characterised by taking the mesania (transitional) varieties as reference,[542] and welcoming elements of the spoken language so as to be perceived as a more "natural" mediation; it also ensured that the common orthography would be provided with the characteristics of over-dialectality and supra-municipality, while being open to integrating the phonetic peculiarities of the local variants.

482/99, only the text written in Italian has legal value), giving citizens the right to write to the Public Administration in their own variety and establishing the regional language desk Ufitziu de sa Limba Sarda.