Gilbert and Sullivan

[1] Gilbert, who wrote the libretti for these operas, created fanciful "topsy-turvy" worlds where each absurdity is taken to its logical conclusion: fairies rub elbows with British lords, flirting is a capital offence, gondoliers ascend to the monarchy, and pirates emerge as noblemen who have gone astray.

[9] In the Bab Ballads and his early plays, Gilbert developed a unique "topsy-turvy" style in which humour was derived by setting up a ridiculous premise and working out its logical consequences, however absurd.

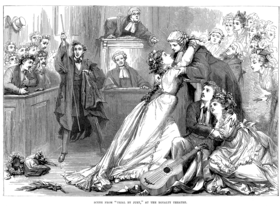

Thus the Learned Judge marries the Plaintiff, the soldiers metamorphose into aesthetes, and so on, and nearly every opera is resolved by a deft moving of the goalposts... His genius is to fuse opposites with an imperceptible sleight of hand, to blend the surreal with the real, and the caricature with the natural.

Public performance followed, with W. S. Gilbert (then writing dramatic criticism for the magazine Fun) saying that Sullivan's score "is, in many places, of too high a class for the grotesquely absurd plot to which it is wedded.

Its mixture of political satire and grand opera parody mimicked Offenbach's Orpheus in the Underworld and La belle Hélène, which (in translation) then dominated the English musical stage.

Gilbert worked with Frederic Clay on Happy Arcadia (1872) and Alfred Cellier on Topsyturveydom (1874) and wrote The Wicked World (1873), Sweethearts (1874) and several other libretti, farces, extravaganzas, fairy comedies, dramas and adaptations.

[25][n 5] In 1874, Gilbert wrote a short libretto on commission from producer-conductor Carl Rosa, whose wife would have played the leading role, but her death in childbirth cancelled the project.

He, too, was a first-rate practical musician.... As he was the most absurd person, so was he the very kindliest...."[30] Fred's creation would serve as a model for the rest of the collaborators' works, and each of them has a crucial comic little man role, as Burnand had put it.

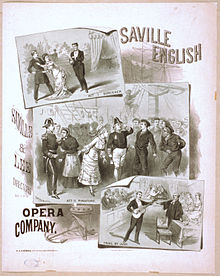

[n 7] Carte's real ambition was to develop an English form of light opera that would displace the bawdy burlesques and badly translated French operettas then dominating the London stage.

Pinafore relied on stock character types, many of which were familiar from European opera (and some of which grew out of Gilbert's earlier association with the German Reeds): the heroic protagonist (tenor) and his love-interest (soprano); the older woman with a secret or a sharp tongue (contralto); the baffled lyric baritone – the girl's father; and a classic villain (bass-baritone).

[46] The repertory system ensured that the comic patter character who performed the role of the sorcerer, John Wellington Wells, would become the ruler of the Queen's navy as Sir Joseph Porter in H.M.S.

These included George Grossmith, the principal comic; Rutland Barrington, the lyric baritone; Richard Temple, the bass-baritone; and Jessie Bond, the mezzo-soprano soubrette.

[46] The Pirates of Penzance (New Year's Eve, 1879) also poked fun at grand opera conventions, sense of duty, family obligation, the "respectability" of civilisation and the peerage, and the relevance of a liberal education.

[43][50] Nevertheless, Pirates was a hit both in New York, again spawning numerous imitators, and then in London, and it became one of the most frequently performed, translated and parodied Gilbert and Sullivan works, also enjoying successful 1981 Broadway[51] and 1982 West End revivals by Joseph Papp that continue to influence productions of the opera.

Sullivan had one installed as well, and on 13 May 1883, at a party to celebrate the composer's 41st birthday, the guests, including the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), heard a direct relay of parts of Iolanthe from the Savoy.

But paradoxically, in February 1883, just after Iolanthe opened, Sullivan had signed a five-year agreement with Gilbert and Carte requiring him to produce a new comic opera on six months' notice.

"[70] Setting the opera in Japan, an exotic locale far away from Britain, allowed Gilbert and Sullivan to satirise British politics and institutions more freely by clothing them in superficial Japanese trappings.

[85] The Yeomen of the Guard (1888), their only joint work with a serious ending, concerns a pair of strolling players – a jester and a singing girl – who are caught up in a risky intrigue at the Tower of London during the 16th century.

Thus the music follows the book to a higher plane, and we have a genuine English opera....[87]Yeomen was a hit, running for over a year, with strong New York and touring productions.

After a brief impasse over the choice of subject, Sullivan accepted an idea connected with Venice and Venetian life, as "this seemed to me to hold out great chances of bright colour and taking music.

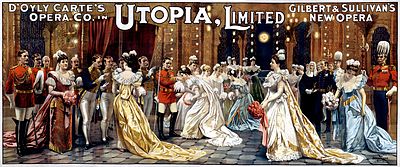

The libretto also reflects Gilbert's fascination with the "Stock Company Act", highlighting the absurd convergence of natural persons and legal entities, which plays an even larger part in the next opera, Utopia, Limited.

"[64] As biographer Andrew Crowther has explained: After all, the carpet was only one of a number of disputed items, and the real issue lay not in the mere money value of these things, but in whether Carte could be trusted with the financial affairs of Gilbert and Sullivan.

[106] Sullivan, by this time in exceedingly poor health, died in 1900, although to the end he continued to write new comic operas for the Savoy with other librettists, most successfully with Basil Hood in The Rose of Persia (1899).

[113] In 1922, Sir Henry Wood explained the enduring success of the collaboration as follows: Sullivan has never had an equal for brightness and drollery, for humour without coarseness and without vulgarity, and for charm and grace.

His verses show an unequalled and very delicate gift for creating a comic effect by the contrast between poetic form and prosaic thought and wording.... How deliciously [his lines] prick the bubble of sentiment.... [Of] equal importance... Gilbert's lyrics almost invariably take on extra point and sparkle when set to Sullivan's music.... Sullivan's tunes, in these operas, also exist in a make-believe world of their own.... [He is] a delicate wit, whose airs have a precision, a neatness, a grace, and a flowing melody....

The influence of Gilbert is discernible in a vein of British comedy that runs through John Betjeman's verse via Monty Python and Private Eye to... television series like Yes Minister... where the emphasis is on wit, irony, and poking fun at the establishment from within it in a way which manages to be both disrespectful of authority and yet cosily comfortable and urbane.

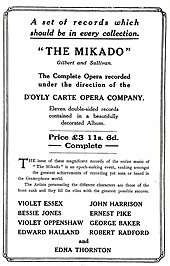

[163][n 16] Well known examples of this include Tom Lehrer's The Elements and Clementine;[164] Allan Sherman's I'm Called Little Butterball, When I Was a Lad, You Need an Analyst and The Bronx Bird-Watcher;[165][166] and The Two Ronnies' 1973 Christmas Special.

[167] Other comedians have used Gilbert and Sullivan songs as a key part of their routines, including Hinge and Bracket,[168] Anna Russell,[169] and the HMS Yakko episode of the animated TV series Animaniacs.

Sullivan's authorship of the overture to Utopia, Limited cannot be verified with certainty, as his autograph score is now lost, but it is likely attributable to him, as it consists of only a few bars of introduction, followed by a straight copy of music heard elsewhere in the opera (the Drawing Room scene).

[178] Very early performances of The Sorcerer used a section of Sullivan's incidental music to Shakespeare's Henry the VIII, as he did not have time to write a new overture, but this was replaced in 1884 by one executed by Hamilton Clarke.