Gilmoreosaurus

In the early twentieth century, the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) conducted a series of palaeontological expeditions to the deserts of Asia.

The Smithsonian had little in terms of a dinosaur fossil collection and Gilmore as such was more reliant on the literature than first hand comparisons in his studies.

This choice was made tentatively; Gilmore was mindful of the possibility his species may later require its own genus, but did not currently feel there was sufficient difference from M. amurensis for this.

[5] One persistent issue surrounding the taxonomy of the Iren Dabasu hadrosaurs was the nature of cranial material found at the Bactrosaurus quarry.

[2] Gilmore assumed, based on its association with the rest of the Bactrosaurus material, that it must belong to that genus; no other elements at the site were inconsistent with just one species being present.

He did consider the possibility it belonged to M. mongoliensis, and also noted its resemblance to specimens of the genus Tanius, but eventually discarded both ideas.

Brett-Surman reported that he and John R. Horner were at work investigating this material to form a more complete understanding of the formations' fauna.

[1] Halszka Osmólska and Teresa Maryańska published a paper in 1981 which focused on Saurolophus angustirostris, but also provided comments on Asian hadrosaurs as a whole.

They disagreed the otherwise monospecific nature of the quarry (i.e. only one species seeming to be present) was stronger evidence than the discordant anatomy of the material.

The relevant new material was frontal remains that the authors considered to be "clearly lambeosaurine" in nature, and so referrable to Bactrosaurus.

[2] The issue would finally be put to rest by Pascal Godefroit and colleagues in 1998, when they published a study describing newly discovered Bactrosaurus material.

The reasoning for the paradoxical nature of the anatomy was that Bactrosaurus was not a lambeosaur or even hadrosaurid at all but instead a more primitive form of hadrosauroid merely convergent with its later relatives.

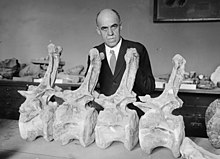

[11] Seeking to finally resolve the longstanding issue, Albert Prieto-Márquez and Mark A. Norrel began work on a thorough redescription of Gilmoreosaurus; this was published in 2010.

[14][15][16] The genus can be distinguished from other hadrosauroid taxa in having a very reduced paddle-shaped postacetabular process and an asymmetrical manual phalanx III-1 end.

The upper surface of the rostral joint forms a flattened socket-like structure that continues towards the rear with the base of the postorbital ramus.

The total dentary teeth count on Gilmoreosaurus was probably less than 30 and the tooth row is oriented to the lateral sides as seen in other hadrosauroids, unlike the more advanced hadrosaurids.

Being relatively elongated, the centra in the three fused vertebrae are platycoelus (slightly concave at both ends) and have the lineal heart-shaped facets.

The lower fifth of the ulna has a flattened articular surface for the radius that faces from the inner to the top facets and shows elongated striations.

The ilium is elongated and shallow in shape with its preacetabular process (anterior expansion of the iliac blade) also being long and deflected towards the bottom.

The lower end of the ischium has a characteristic "foot-like" expansion and though its bottom border is eroded, enough is preserved to tell that it was not greatly expanded in this area.

The anterior trochanter is elongated and large, being forwards offset and excluded from the lateral surface of the upper region of the femur by a fissure.

Several hadrosaurs were histologically analyzed, including Barsboldia, Gobihadros, Saurolophus and ZPAL MgD-III/2-17, an indeterminate second species of hadrosauroid present in the Bayan Shireh Formation.

The latter was slightly smaller than Gobihadros as seen on the developed external fundamental system (tightly spaced LAGs that indicate adulthood) on the tibia.

Slowiak and colleagues noted that the growth trend within the Hadrosauroidea featured two important adaptations of bone microstructure similar to those of Eusauropoda.

The first important adaptation was the decrease of secondary remodelling in the tibia, allowing the bone to bear higher tensions.

This feature is thought to represent a biomechanical response to their increasing body-size evolution since the center of mass was concentrated on the pelvic area and therefore supported by well-developed hindlimbs.

Evidence of tumors, including hemangiomas, desmoplastic fibroma, metastatic cancer, and osteoblastoma were discovered in numerous specimens of Gilmoreosaurus by analyzing them through computerized tomography and fluoroscope screening.

The tumors were only found on caudal vertebrae and they may have been caused by environmental factors, such as the way in which these hadrosaurs interacted with their environments, making them more susceptible to get cancer, or, through genetic inheritance.

[19] Gilmoreosaurus is known from the Late Cretaceous Iren Dabasu Formation, which has been dated back to the Cenomanian stage around 95.8 ± 6.2 million years ago.

Extensive vegetation that maintained a great variety of herbivorous dinosaurs was also present on the formation as seen on the multiple skeletons of hadrosauroids, the prominent paleosol and the numerous palynological occurrences.