Edmontosaurus mummy AMNH 5060

Discovered in 1908 in the United States near Lusk, Wyoming, it was the first dinosaur specimen found to include a skeleton encased in skin impressions from large parts of the body.

Although Sternberg was working under contract to the British Museum of Natural History, Henry Fairfield Osborn of the AMNH managed to secure the mummy.

Skin impressions found in between the fingers were once interpreted as interdigital webbing, bolstering the now-rejected perception of hadrosaurids as aquatic animals, a hypothesis that remained unchallenged until 1964.

In contrast with other similar dinosaur mummies, the skin of AMNH 5060 was tightly attached to the bones and partially drawn into the body interior, indicating that the carcass dried out before burial.

Nothing.At the end of August, Sternberg finally discovered a fossil horn weathering out of the rock; subsequent excavation revealed a 19 cm (7.5 in) long Triceratops skull.

When removing a large piece of sandstone from the chest region of the specimen, George discovered, to his surprise, a perfectly preserved skin impression.

In the exhibition, the mummy, protected by a glass showcase, is shown lying on its back as it was discovered; the museum decided not to restore missing parts.

[11] The scientific value of the mummy lies in its exceptionally high degree of preservation, the articulation of the bones in their original anatomical position, and the extensive skin impressions enveloping the specimen.

[1] As noted by Osborn in 1912, the famous holotype specimen of Trachodon mirabilis (AMNH 5730), found in 1884 by Jacob Wortman, originally also contained extensive skin impressions, but most had been destroyed during excavation, leaving only three fragments from the tail region.

This term was later used by some authors to refer to a handful of similar hadrosaurid ("duck-billed dinosaurs") specimens with extensive skin impressions, all of which have been discovered in North America.

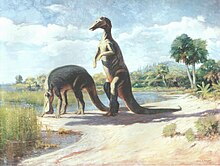

[15] Gregory S. Paul, in 1987, stated that the life appearance of Edmontosaurus and Corythosaurus can be more accurately restored than that of any other dinosaur thanks to the well-preserved mummy specimens.

Yet, evidence provided by AMNH 5060 was not regularly taken into account by paleoartists, possibly because it was described before World War I, during which activity in dinosaur research abated, only to be revitalized in the mid 1960s.

[8] Although the tail curves upwards and forwards over the body in many dinosaur skeletons, it was probably straight in the mummy as movement would have been restricted by ossified tendons.

[5] In 2007, paleontologist Kenneth Carpenter suggested that even impressions of inner organs are possibly preserved; this cannot be evaluated without detailed computer tomography and x-ray analyses.

An Edmontosaurus fossil described by the paleontologist John Horner in 1984 shows a regular row of rectangular lobes in the tail area.

Furthermore, Osborn noted the lack of clearly pronounced hooves and large fleshy foot pads on the forelimb—features to be expected in a primarily land-dwelling animal.

A possible aquatic lifestyle of hadrosaurids had been proposed before, in particular based on the great depth and flat sides of a well-preserved tail discovered by Brown in 1906.

This hypothesis appeared to be in accordance with an 1883 account by Edward Drinker Cope describing hadrosaurid teeth as "slightly attached" and "delicate", and therefore suitable for feeding on soft aquatic plants.

Ostrom noted that hadrosaurids showed no osteoderms or similar structures to defend against predators that are found in many other herbivorous dinosaurs, and suggested that the webs may have been used to allow escape into the water in case of danger.

[29] Robert Bakker, in 1986, argued that the animal had no webs, and that the skin between its fingers was the remnant of a fleshy pad enveloping the hand that had dried out and flattened during mummification.

Although the palms of the mummy face backwards, this is because the carcass lay on its back, which caused the forelimbs to sprawl and the humeri to detach from the shoulder joints.

[27] In 2015, Philip Manning and colleagues concluded that skin in dinosaur mummies is not simply preserved as an impression but contains original biomolecules or their derivatives.

In 2015, however, Albert Prieto-Márquez and Jonathan Wagner found low and subtle impressions of polygonal scales in the frontmost part of the depression behind the beak.

The gases accumulating in the abdomen after death would have floated the carcass, with the belly pointing upwards and the head moving into its final position under the shoulder.

[4] Osborn suggested another scenario in 1911: the animal could have died a natural death, and the carcass would have been exposed to the sun for a longer time in a dry riverbed, unaffected by scavengers.

Muscles and intestines would have completely dried out and thus shrunk, whereby the hard and leathery skin sank into the body cavity and finally adhered tightly to the bones, forming a natural mummy.

At the end of the dry season, the mummy would have been hit by a sudden flood, transported a distance and quickly covered with sediments at the embedding site.

Carpenter concluded from a photograph taken during the excavation that the mummy was discovered within such a point bar, and suspected that the carcass was embedded during flood events after the end of a drought.

Additional sediment that led to further burial would have originated from cut banks collapsing into the river further upstream, which is indicated by the high clay content of the sandstones.

After the more or less complete decomposition of the soft tissue, a cavity remained in the cemented sediment that was subsequently filled with sand, together with the skin impression it contained.