Ginkgo

The closest living relatives of the clade are the cycads,[4] which share with the extant G. biloba the characteristic of motile sperm.

Given the slow pace of evolution and morphological similarity between members of the genus, there may have been only one or two species existing in the Northern Hemisphere through the entirety of the Cenozoic: present-day G. biloba (including G. adiantoides) and G. gardneri from the Palaeocene of Scotland.

While it may seem improbable that a species may exist as a contiguous entity for many millions of years, many of the ginkgo's life-history parameters fit.

The sediment records at the majority of fossil Ginkgo localities indicate it grew primarily in disturbed environments along streams and levees.

[8] Ginkgo therefore presents an "ecological paradox" because, while it possesses some favourable traits for living in disturbed environments (clonal reproduction), many of its other life-history traits (slow growth, large seed size, late reproductive maturity) are the opposite of those exhibited by "younger", more-recently emerged plant species that thrive in disturbed settings.

[10] Given the slow rate of evolution of the genus, it is possible that Ginkgo represents a pre-angiosperm strategy for survival in disturbed streamside environments.

Ginkgo evolved in an era before angiosperms (flowering plants), when ferns, cycads, and cycadeoids dominated disturbed streamside environments, forming a low, open, shrubby canopy.

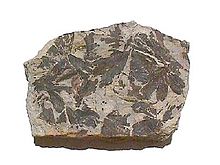

Sphenobaiera (early Permian–Cretaceous) had wedge-shaped leaves divided into narrow dichotomously-veined lobes, lacking distinct petioles (leaf stalks).

[13]: 743–756 As of February 2013[update], molecular phylogenetic studies have produced at least six different placements of Ginkgo relative to cycads, conifers, gnetophytes and angiosperms.