Herbal

A herbal is a book containing the names and descriptions of plants, usually with information on their medicinal, tonic, culinary, toxic, hallucinatory, aromatic, or magical powers, and the legends associated with them.

[4] Herbals were among the first literature produced in Ancient Egypt, China, India, and Europe[5] as the medical wisdom of the day accumulated by herbalists, apothecaries and physicians.

In Europe, the first printed herbal with woodcut (xylograph) illustrations, the Puch der Natur of Konrad of Megenberg, appeared in 1475.

[19] As woodcuts and metal engravings could be reproduced indefinitely they were traded among printers: there was therefore a large increase in the number of illustrations together with an improvement in quality and detail but a tendency for repetition.

[27] Traditional herbal medicine of India, known as Ayurveda, possibly dates back to the second millennium BCE tracing its origins to the holy Hindu Vedas and, in particular, the Atharvaveda.

[30] An illustrated herbal published in Mexico in 1552, Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis ("Book of Medicinal Herbs of the Indies"), is written in the Aztec Nauhuatl language by a native physician, Martín Cruz.

This is probably an extremely early account of the medicine of the Aztecs although the formal illustrations, resembling European ones, suggest that the artists were following the traditions of their Spanish masters rather than an indigenous style of drawing.

[34] With the formation of the Alexandrian School c. 330 BCE medicine flourished and written herbals of this period included those of the physicians Herophilus, Mantias, Andreas of Karystos, Appolonius Mys, and Nicander.

[40] Another Latin translation of Greek works that was widely copied in the Middle Ages, probably illustrated in the original, was that attributed to Apuleius: it also contained the alternative names for particular plants given in several languages.

Many of the monks were skilled at producing books and manuscripts and tending both medicinal gardens and the sick, but written works of this period simply emulated those of the classical era.

[42] Meanwhile, in the Arab world, by 900 the great Greek herbals had been translated and copies lodged in centres of learning in the Byzantine empire of the eastern Mediterranean including Byzantium, Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad where they were combined with the botanical and pharmacological lore of the Orient.

Those associated with this period include Mesue Maior (Masawaiyh, 777–857) who, in his Opera Medicinalia, synthesised the knowledge of Greeks, Persians, Arabs, Indians and Babylonians, this work was complemented by the medical encyclopaedia of Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037).

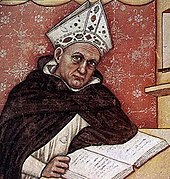

[51] In the thirteenth century, scientific inquiry was returning and this was manifest through the production of encyclopaedias; those noted for their plant content included a seven volume treatise by Albertus Magnus (c. 1193–1280) a Suabian educated at the University of Padua and tutor to St Thomas Aquinas.

It was called De Vegetabilibus (c. 1256 AD) and even though based on original observations and plant descriptions it bore a close resemblance to the earlier Greek, Roman and Arabic herbals.

[52] Other accounts of the period include De Proprietatibus Rerum (c. 1230–1240) of English Franciscan friar Bartholomaeus Anglicus and a group of herbals called Tractatus de Herbis written and painted between 1280 and 1300 by Matthaeus Platearius at the East-West cultural centre of Salerno Spain, the illustrations showing the fine detail of true botanical illustration.

The new herbals were more detailed with greater general appeal and often with Gothic script and the addition of woodcut illustrations that more closely resembled the plants being described.

[57] In the Modern Age and Renaissance, European herbals diversified and innovated, and came to rely more on direct observation than being mere adaptations of traditional models.

The first printed herbal appeared in 1469, a version of Pliny's Historia Naturalis; it was published nine years before Dioscorides De Materia Medica was set in type.

To these can be added Macer’s De Virtutibus Herbarum, based on Pliny's work; the 1477 edition is one of the first printed and illustrated herbals.

The De Synonymis and other publications of Simon Januensis, the Liber Servitoris of Bulchasim Ben Aberazerim, which described the preparations made from plants, animals and minerals, provided a model for the chemical treatment of modern pharmacopoeias.

Otto Brunfels (c. 1489–1534), Leonhart Fuchs (1501–1566) and Hieronymus Bock (1498–1554) were known as the "German fathers of botany"[64] although this title belies the fact that they trod in the steps of the scientifically celebrated Hildegard of Bingen whose writings on herbalism were Physica and Causae et Curae (together known as Liber subtilatum) of 1150.

[66] The 1530, Herbarum Vivae Eicones of Brunfels contained the admired botanically accurate original woodcut colour illustrations of Hans Weiditz along with descriptions of 47 species new to science.

De Historia Stirpium (1542 with a German version in 1843) of Fuchs was a later publication with 509 high quality woodcuts that again paid close attention to botanical detail: it included many plants introduced to Germany in the sixteenth century that were new to science.

[68] The Flemish printer Christopher Plantin established a reputation publishing the works of Dutch herbalists Rembert Dodoens and Carolus Clusius and developing a vast library of illustrations.

Prospero Alpini (1553–1617) published in 1592 the highly popular account of overseas plants De Plantis Aegypti and he also established a botanical garden in Padua in 1542, which together with those at Pisa and Florence, rank among the world's first.

His three-part A New Herball of 1551–1562–1568, with woodcut illustrations taken from Fuchs, was noted for its original contributions and extensive medicinal content; it was also more accessible to readers, being written in vernacular English.

It appears to be a reformulation of Hieronymus Bock's Kreuterbuch subsequently translated into Dutch as Pemptades by Rembert Dodoens (1517–1585), and thence into English by Carolus Clusius, (1526–1609) then re-worked by Henry Lyte in 1578 as A Nievve Herball.

Parkinson is celebrated for his two monumental works, the first Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris in 1629: this was essentially a gardening book, a florilegium for which Charles I awarded him the title Botanicus Regius Primarius – Royal Botanist.

This was the first glimpse of non-anthropocentric botanical science since Theophrastus and, coupled with the new system of binomial nomenclature, resulted in "scientific herbals" called Floras that detailed and illustrated the plants growing in a particular region.

As herbal historian Agnes Arber remarks – "Sibthorp's monumental Flora Graeca is, indeed, the direct descendant in modern science of the De Materia Medica of Dioscorides.