Gioachino Rossini

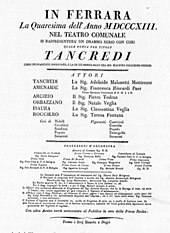

In the period 1810–1823, he wrote 34 operas for the Italian stage that were performed in Venice, Milan, Ferrara, Naples and elsewhere; this productivity necessitated an almost formulaic approach for some components (such as overtures) and a certain amount of self-borrowing.

The rest of his education was consigned to the legitimate school of southern youth, the society of his mother, the young singing girls of the company, those prima donnas in embryo, and the gossips of every village through which they passed.

[19] He studied the horn with his father and other music with a priest, Giuseppe Malerbe, whose extensive library contained works by Haydn and Mozart, both little known in Italy at the time, but inspirational to the young Rossini.

He declined the offer: the strict academic regime of the Liceo had given him a solid compositional technique, but as his biographer Richard Osborne puts it, "his instinct to continue his education in the real world finally asserted itself".

The city had once been the operatic capital of Europe;[38] the memory of Cimarosa was revered and Paisiello was still living, but there were no local composers of any stature to follow them, and Rossini quickly won the public and critics round.

[41] For the first time, Rossini was able to write regularly for a resident company of first-rate singers and a fine orchestra, with adequate rehearsals, and schedules that made it unnecessary to compose in a rush to meet deadlines.

[n 13] Despite an unsuccessful opening night, with mishaps on stage and many pro-Paisiello and anti-Rossini audience members, the opera quickly became a success, and by the time of its first revival, in Bologna a few months later, it was billed by its present Italian title and it rapidly eclipsed Paisiello's setting.

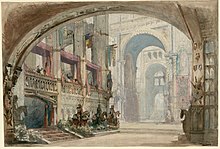

[44] Among his other works for the house were Mosè in Egitto, based on the biblical story of Moses and the Exodus from Egypt (1818), and La donna del lago, from Sir Walter Scott's poem The Lady of the Lake (1819).

[62] The work survived that one major disadvantage, and entered the international operatic repertory, remaining popular throughout the 19th century;[63] in Richard Osborne's words, it brought "[Rossini's] Italian career to a spectacular close.

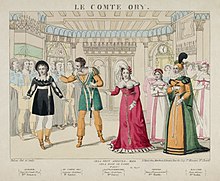

As well as dropping some of the original music that was in an ornate style unfashionable in Paris, Rossini accommodated local preferences by adding dances, hymn-like numbers and a greater role for the chorus.

His determination to reuse music from Il viaggio a Reims caused problems for his librettists, who had to adapt their original plot and write French words to fit existing Italian numbers, but the opera was a success, and was seen in London within six months of the Paris premiere, and in New York in 1831.

He had contracted gonorrhoea in earlier years, which later led to painful side-effects, from urethritis to arthritis;[102] he suffered from bouts of debilitating depression, which commentators have linked to several possible causes: cyclothymia,[103] or bipolar disorder,[104] or reaction to his mother's death.

His return to Paris in 1843 for medical treatment by Jean Civiale sparked hopes that he might produce a new grand opera – it was rumoured that Eugène Scribe was preparing a libretto for him about Joan of Arc.

Once settled in Paris he maintained two homes: a flat in the rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, a smart central area, and a neo-classical villa built for him in Passy, a commune now absorbed into the city, but then semi-rural.

Such gatherings were a regular feature of Parisian life – the writer James Penrose has observed that the well-connected could easily attend different salons almost every night of the week – but the Rossinis' samedi soirs quickly became the most sought after: "an invitation was the city's highest social prize.

[126] He left Olympe a life interest in his estate, which after her death, ten years later, passed to the Commune of Pesaro for the establishment of a Liceo Musicale, and funded a home for retired opera singers in Paris.

His basic formula for these remained constant throughout his career: Gossett characterises them as "sonata movements without development sections, usually preceded by a slow introduction" with "clear melodies, exuberant rhythms [and] simple harmonic structure" and a crescendo climax.

[133] Richard Taruskin also notes that the second theme is always announced in a woodwind solo, whose "catchiness" "etch[es] a distinct profile in the aural memory", and that the richness and inventiveness of his handling of the orchestra, even in these early works, marks the start of "[t]he great nineteenth-century flowering of orchestration.

This model could be adapted in various ways so as to forward the plot (as opposed to the typical eighteenth-century handling which resulted in the action coming to a halt as the requisite repeats of the da capo aria were undertaken).

[140] A landmark in this context is the cavatina "Di tanti palpiti" from Tancredi, which both Taruskin and Gossett (amongst others) single out as transformative, "the most famous aria Rossini ever wrote",[141] with a "melody that seems to capture the melodic beauty and innocence characteristic of Italian opera.

"[45][n 31] Both writers point out the typical Rossinian touch of avoiding an "expected" cadence in the aria by a sudden shift from the home key of F to that of A flat (see example); Taruskin notes the implicit pun, as the words talk of returning, but the music moves in a new direction.

Tuneful and engaging, they indicate how remote the talented child was from the influence of the advances in musical form evolved by Mozart, Haydn and Beethoven; the accent is on cantabile melody, colour, variation and virtuosity rather than transformational development.

"[150] Rossini's contract did not prevent him from undertaking other commissions, and before Otello, Il barbiere di Siviglia, a grand culmination of the opera buffa tradition, had been premiered in Rome (February 1816).

Richard Osborne catalogues its excellencies: Beyond the physical impact of ... Figaro's "Largo al factotum", there is Rossini's ear for vocal and instrumental timbres of a peculiar astringency and brilliance, his quick-witted word-setting, and his mastery of large musical forms with their often brilliant and explosive internal variations.

This becomes clear from the overture, which is explicitly programmatic in describing weather, scenery and action, and presents a version of the Ranz des Vaches, the Swiss cowherd's call, which "undergoes a number of transformations during the opera" and gives it in Richard Osborne's opinion "something of the character of a leitmotif".

Thus, the role of the soloists is significantly reduced compared to other Rossini operas, the hero not even having an aria of his own, whilst the chorus of the Swiss people is consistently in the musical and dramatic foregrounds.

Living in Bologna, he occupied himself teaching singing at the Liceo Musicale, and also created a pasticcio of Tell, Rodolfo di Sterlinga, for the benefit of the singer Nicola Ivanoff [it], for which Giuseppe Verdi provided some new arias.

Examples include Sigismond Thalberg's fantasy on themes from Moïse,[168] the sets of variations on "Non più mesta" from La Cenerentola by Henri Herz, Frédéric Chopin, Franz Hünten, Anton Diabelli and Friedrich Burgmüller,[169] and Liszt's transcriptions of the William Tell overture (1838) and the Soirées musicales.

Opéras comiques showing a debt to Rossini's style include François-Adrien Boieldieu's La dame blanche (1825) and Daniel Auber's Fra Diavolo (1830), as well as works by Ferdinand Hérold, Adolphe Adam and Fromental Halévy.

[174][175] Critical of Rossini's style was Hector Berlioz, who wrote of his "melodic cynicism, his contempt for dramatic and good sense, his endless repetition of a single form of cadence, his eternal puerile crescendo and his brutal bass drum".