Giraffatitan

Giraffatitan (name meaning "titanic giraffe") is a genus of sauropod dinosaur that lived during the late Jurassic Period (Kimmeridgian–Tithonian stages) in what is now Lindi Region, Tanzania.

Only one species is known, G. brancai, named in honor of German paleontologist Wilhelm von Branca, who was a driving force behind the expedition that discovered it in the Tendaguru Formation.

Arning again informed the Kommission für die landeskundliche Erforschung der Schutzgebiete, a commission in Berlin overviewing the geographical investigation of German protectorates.

[4] In the summer of 1907, Fraas, already for some months travelling the colony, received a letter from Dr Hans Meyer in Leipzig urging him to investigate Sattler's discovery.

He managed to attract the interest of Professor Wilhelm von Branca, the head of the Geologisch-Paläontologische Institut und Museum der Königliche Friedrich-Wilhelm Universität zu Berlin.

It contained a relatively complete skeleton of a medium-sized individual, lacking the hands, the neck, the back vertebrae and the skull.

On the basis of its scapula (shoulder blade) and humerus (upper arm bone) Brachiosaurus fraasi was erected, which later turned out to be a junior synonym of B. brancai.

In dozens of other Tendaguru locations, finds were made of large single sauropod bones that were referred to the taxon in Janensch's publications but of which no field notes survive so that the precise circumstances of the discoveries are unknown.

Therefore, Janensch described it as Brachiosaurus brancai, choosing the species name in honor of Wilhelm von Branca, then director of the Museum für Naturkunde and a driving force behind the Tendaguru expedition.

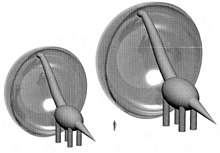

In the later part of the twentieth century, several giant titanosaurians found appear to surpass Giraffatitan in terms of sheer mass.

There are also a large number of such estimations as the skeleton proved to be an irresistible subject for researchers wanting to test their new measuring methods.

Gregory S. Paul in 1988 assumed that the, in his opinion, unrealistically high number had been caused by the fact that such models used to be very bloated compared to the real build of the animal.

[18] In 1980, Dale Alan Russell et al published a much lower weight of 14.8 tonnes by extrapolating from the diameter of the humerus and the thighbone.

[26] In 1985, Robert McNeill Alexander found a value of 46.6 tonnes inserting a toy model of the British Museum of Natural History into water.

[28] In 1995 a laser scan of the skeleton was used to build a virtual model from simple geometrical shapes, finding a volume of 74.42 m3 and concluding to a weight of 63 tonnes.

[2] Giraffatitan was a sauropod, one of a group of four-legged, plant-eating dinosaurs with long necks and tails and relatively small brains.

The skull had a tall arch anterior to the eyes, consisting of the bony nares, a number of other openings, and "spatulate" teeth (resembling chisels).

[38] These assignments were often based on broad similarities rather than unambiguous synapomorphies, shared new traits, and most of these genera are currently regarded as dubious.

[42] Since the 1990s, computer-based cladistic analyses allow for postulating detailed hypotheses on the relationships between species, by calculating those trees that require the fewest evolutionary changes and thus are the most likely to be correct.

[43] In 1997, he published an analysis in which species traditionally considered brachiosaurids were subsequent offshoots of the stem of a larger grouping, the Titanosauriformes, and not a separate branch of their own.

In contrast to earlier studies, Taylor treated both genera as distinct units in a cladistic analysis, finding them to be sister groups.

[45] Several subsequent analyses have found Brachiosaurus and Giraffatitan not to be sister groups, but instead located at different positions on the evolutionary tree.

[21] A 2012 study on titanosauriform sauropods by Michael D'Emic placed Giraffatitan as sister to a clade containing Brachiosaurus and a tritomy of Abydosaurus, Cedarosaurus and Venenosaurus as shown in the cladogram below:[46] Europasaurus Giraffatitan Brachiosaurus Abydosaurus Cedarosaurus Venenosaurus In their 2024 description of Gandititan, Han et al. analyzed the phylogenetic relations of Macronaria, focusing on titanosauriform taxa.

In past decades, scientists theorized that the animal used its nostrils like a snorkel, spending most of its time submerged in water in order to support its great mass.

Studies have demonstrated that water pressure would have prevented the animal from breathing effectively while submerged and that its feet were too narrow for efficient aquatic use.

[51] Czerkas speculated on the function of the peculiar brachiosaurid nose, and pointed out that there was no conclusive way to determine where the nostrils where located, unless a head with skin impressions was found.

[52] It has been proposed that sauropods, including Giraffatitan, may have had proboscises (trunks) based on the position of the bony narial orifice, to increase their upward reach.

[54] As a warm-blooded animal, the daily energy demands of Giraffatitan would have been enormous; it would probably have needed to eat more than 182 kilograms (400 lb) of food per day.

[60] Giraffatitan would have coexisted with fellow sauropods like Dicraeosaurus hansemanni and D. sattleri, Janenschia robusta, Tendaguria tanzaniensis and Tornieria africanus; ornithischians like Dysalotosaurus lettowvorbecki and Kentrosaurus aethiopicus; the theropods "Allosaurus" tendagurensis, "Ceratosaurus" roechlingi, "Ceratosaurus" ingens, Elaphrosaurus bambergi, Veterupristisaurus milneri and Ostafrikasaurus crassiserratus; and the pterosaur Tendaguripterus recki.

[61][62][63][64] Other organisms that inhabited the Tendaguru included corals, echinoderms, cephalopods, bivalves, gastropods, decapods, sharks, neopterygian fish, crocodilians and small mammals like Brancatherulum tendagurensis.