Glen Canyon Dam

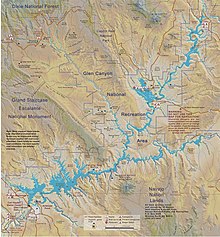

It was believed to represent the annual flow as measured at Lee's Ferry, Arizona (the official dividing point of the upper and lower basins), 16 miles (26 km) downstream of present-day Glen Canyon Dam.

The Echo Park dam would be inside the federally protected Dinosaur National Monument and would submerge 110 miles (180 km) of scenic canyons – a move that alarmed environmentalists.

Floyd Dominy, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, was a vital figure in pushing the project through Congress and convincing politicians to take a pro-dam stance, and to assuage rising public concerns.

"[42] With the necessary political support secured, the Colorado River Storage Project was authorized in April 1956, and groundbreaking of Glen Canyon Dam began in October of the same year.

"[49] Emboldened by Echo Park and desperate to prevent the Grand Canyon from reaching the same fate as Glen, Brower and the Sierra Club directed attention towards the proposed Bridge and Marble dams.

[51] As early as 1947, the Bureau of Reclamation had begun investigating two potential sites, both located in the narrow lower reaches of Glen Canyon shortly upstream of Lee's Ferry.

The contract for building the bridge was awarded to Peter Kiewit Sons and the Judson Pacific Murphy Co. for $4 million and construction began in late 1956, reaching completion on August 11, 1957.

[55] On October 15, 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower pressed a button on his desk in Washington, D.C., sending a telegraph signal that set off the first blast of dynamite at the portal of the right diversion tunnel.

The upper cofferdam was 168 feet (51 m) high, and it alone could store several million acre-feet of water to protect the dam site from flooding in the event that inflows exceeded the capacity of the diversion tunnels.

[80] In March, Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall ordered the filling halted and extra releases made to Lake Mead, to the consternation of the Upper Basin states.

[84] One of the main reasons for this slow rise, in addition to the need to meet obligations to the Lower Basin, was the leakage of vast amounts of water into the porous Navajo Sandstone aquifer.

[86] The Bureau of Reclamation projected that once Lake Powell filled, the total bank storage would stabilize at approximately 6 million acre-feet (7.4 km3), and henceforth would fluctuate depending on water levels in the reservoir.

Snowfall during April and May was exceptionally heavy; this combined with a sudden rise in temperatures and unusual rainstorms in June to produce major flooding across the western United States.

Upon inspection, it was found that cavitation had caused massive gouging damage to both spillways, carrying away thousands of tons of concrete, steel rebar and huge chunks of rock.

One of the earliest debates regarding the dam was its impact on Rainbow Bridge National Monument, whose 290-foot (88 m) high natural arch is the highest in North America, and is a sacred site to the Navajo people.

Abbey's book is discussed in Ecospeak: Rhetoric and Environmental Politics in America (1992) by Jimmie Killingsworth and Jacqueline Palmer, who write that Glen Canyon Dam became "the big symbol of all that blocked freedom in the interests of civilized progress.

[105][106] In his comprehensive history of western water development, Cadillac Desert (1986), Marc Reisner criticized the political forces that resulted in Glen Canyon and hundreds of other dams being built in the 1960s and 1970s.

Many of these projects had dubious economic justifications and hidden environmental costs, but the government agencies that built them – namely the Bureau of Reclamation and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – were more interested in maintaining their size and influence.

Glen Canyon Dam would remain in place (as total removal of the structure would be prohibitively expensive), but would only store water in wet seasons when runoff exceeds the capacity of Lake Mead to hold it.

The engineers wanted the dam to rely predominantly on its arch shape to carry the tremendous pressure of the impounded water into the canyon walls instead of depending on the sheer weight of the structure to hold the reservoir back, as had been done at Hoover.

[124] Glen Canyon Dam's most vital purpose is to provide storage to ensure enough water flows from the Upper Colorado River Basin to the lower, especially in drought years.

Revenues derived from power sales were integral in paying off the bonds used to build the dam and have also been used to fund other Bureau of Reclamation projects, including environmental restoration programs in the Grand Canyon and elsewhere along the Colorado River.

[7] Hydropower generated at Glen Canyon serves about 5 million people in Arizona, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming, and is sold to utilities in these states as 20-year contracts.

Flood control has also caused an inability of the river to carry away the rockslides that are common along the canyons, leading to the creation of incrementally dangerous rapids that pose a hazard to fish and boaters alike.

[151][152] Nikolai Ramsey of the Grand Canyon Trust describes the clearer, colder river as a "death zone for native fish",[153] such as the endemic Colorado pikeminnow and humpback chub, which are adapted to survive in warm, silty water.

[156] On March 26, 1996, the penstocks and two of the outlet works' bypass tubes at Glen Canyon Dam were opened to maximum capacity, causing a flood of 45,000 cubic feet per second (1,300 m3/s) to move down the Colorado River.

[157] The flow appeared to have scoured clean numerous pockets of encroaching vegetation, carried away rockslides that had become dangerous to boaters, and rearranged sand and gravel bars along the river, and was initially believed to be an environmental success.

[164] The high-flow experiments do not change the total amount of water outflow from Lake Powell on an annual basis, but as a consequence hydro-electric power releases during the rest of the year must be reduced.

[165] About 85,000 people per year travel via boat to Rainbow Bridge in Utah, a large natural arch once very hard to access, but now easily reachable because one of the arms of the reservoir extends near it.

[172] Because of the cold, clear water released from Lake Powell, the stretch of the Colorado River between Glen Canyon Dam and Lee's Ferry has become an excellent rainbow trout fishery.