Glia

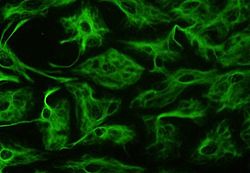

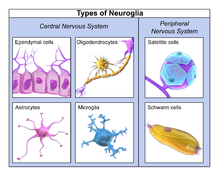

Astrocytes (also called astroglia) have numerous projections that link neurons to their blood supply while forming the blood–brain barrier.

They regulate the external chemical environment of neurons by removing excess potassium ions and recycling neurotransmitters released during synaptic transmission.

Extracellular release of ATP and consequent activation of purinergic receptors on other astrocytes may also mediate calcium waves in some cases.

Protoplasmic astrocytes have short, thick, highly branched processes and are typically found in gray matter.

[14] Ependymal cells, also named ependymocytes, line the spinal cord and the ventricular system of the brain.

[17] Similar in function to oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells provide myelination to axons in the peripheral nervous system (PNS).

Like astrocytes, they are interconnected by gap junctions and respond to ATP by elevating the intracellular concentration of calcium ions.

Glia cells are thought to have many roles in the enteric system, some related to homeostasis and muscular digestive processes.

[22] They are derived from the earliest wave of mononuclear cells that originate in yolk sac blood islands early in development, and colonize the brain shortly after the neural precursors begin to differentiate.

In the healthy central nervous system, microglia processes constantly sample all aspects of their environment (neurons, macroglia and blood vessels).

[24] Tanycytes in the median eminence of the hypothalamus are a type of ependymal cell that descend from radial glia and line the base of the third ventricle.

[25] Drosophila melanogaster, the fruit fly, contains numerous glial types that are functionally similar to mammalian glia but are nonetheless classified differently.

[27] The total number of glia cells in the human brain is distributed into the different types with oligodendrocytes being the most frequent (45–75%), followed by astrocytes (19–40%) and microglia (about 10% or less).

In the adult, microglia are largely a self-renewing population and are distinct from macrophages and monocytes, which infiltrate an injured and diseased CNS.

The view is based on the general inability of the mature nervous system to replace neurons after an injury, such as a stroke or trauma, where very often there is a substantial proliferation of glia, or gliosis, near or at the site of damage.

During early embryogenesis, glial cells direct the migration of neurons and produce molecules that modify the growth of axons and dendrites.

Glial cells known as astrocytes enlarge and proliferate to form a scar and produce inhibitory molecules that inhibit regrowth of a damaged or severed axon.

Oligodendrocytes are found in the CNS and resemble an octopus: they have bulbous cell bodies with up to fifteen arm-like processes.

[39] While glial cells in the PNS frequently assist in regeneration of lost neural functioning, loss of neurons in the CNS does not result in a similar reaction from neuroglia.

[40] Generally, when damage occurs to the CNS, glial cells cause apoptosis among the surrounding cellular bodies.

[40] Then, there is a large amount of microglial activity, which results in inflammation, and, finally, there is a heavy release of growth inhibiting molecules.

[47] These important scientific findings may begin to shift the neurocentric perspective into a more holistic view of the brain which encompasses the glial cells as well.

For the majority of the twentieth century, scientists had disregarded glial cells as mere physical scaffolds for neurons.

Recent publications have proposed that the number of glial cells in the brain is correlated with the intelligence of a species.