Gliosis

Gliosis has historically been given a negative connotation due to its appearance in many CNS diseases and the inhibition of axonal regeneration caused by glial scar formation.

However, gliosis has been shown to have both beneficial and detrimental effects, and the balance between these is due to a complex array of factors and molecular signaling mechanisms, which affect the reaction of all glial cell types.

[3] Like other forms of gliosis, astrogliosis accompanies traumatic brain injury as well as many neuropathologies, ranging from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis to fatal familial insomnia.

In fact, it is a spectrum of changes that occur based on the type and severity of central nervous system (CNS) injury or disease triggering the event.

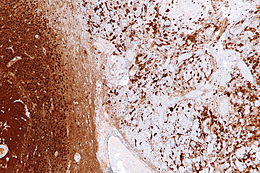

[5] The severity of astrogliosis is classically determined by the level of expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin, both of which are upregulated with the proliferation of active astrocytes.

[5] Although astrogliosis has traditionally been viewed as a negative response inhibitory to axonal regeneration, the process is highly conserved, suggesting it has important benefits beyond its detrimental effects.

Within the first week following the injury, microglia begin to proliferate abnormally and while doing so exhibit several immunophenotypic changes, particularly an increased expression of MHC antigens.

[4] Notably, unlike astrogliosis, microgliosis is a temporary and self-limited event, which generally lasts only one month after injury, even in cases of extreme damage.

[4] Oligodendrocytes are another type of glial cell which generate and maintain the formation of myelin around the axons of large neurons in the CNS, allowing for rapid transmission of neural signals.

Gliosis in any form entails an alteration in cellular activity that has the potential to create widespread effects on neurons as well as other non-neural cells, causing either a loss of normal functions or a gain of detrimental ones.

These astrocytes often exhibit extreme hypertrophy and multiple distinct nuclei, and their production of pro-inflammatory molecules has been implicated in several inflammatory disorders.

[14] Cytokines produced by both active astrocytes and microglia in inflammatory conditions may contribute to myelin damage and may alter blood-brain barrier permeability, allowing the migration of lymphocytes into the CNS and heightening the autoimmune attack.

Upon retinal injury, gliosis of these cells occurs, functioning to repair damage, but often having harmful consequences in the process, worsening some of the diseases or problems that initially trigger it.

[16] Reactive gliosis in the retina can have detrimental effects on vision; in particular, the production of proteases by astrocytes causes widespread death of retinal ganglion cells.

[17] Massive retinal gliosis (MRG) is a phenomenon in which the retina is completely replaced by proliferation of glial cells, causing deterioration of vision and even blindness in some cases.

Sometimes mistaken for an intraocular tumor, MRG can arise from a neurodegenerative disease, congenital defect, or from trauma to the eyeball, sometimes appearing years after such an incident.

Gliosis and glial scarring occur in areas surrounding the amyloid plaques which are hallmarks of the disease, and postmortem tissues have indicated a correlation between the degree of astrogliosis and cognitive decline.

[7][14] Exposure of reactive astrocytes to β-amyloid (Αβ) peptide, the main component of amyloid plaques, may also induce astroglial dysfunction and neurotoxicity.

Because gliosis is a dynamic process which involves a spectrum of changes depending on the type and severity of the initial insult, to date, no single molecular target has been identified which could improve healing in all injury contexts.

One promising therapeutic mechanism is the use of β-lactam antibiotics to enhance the glutamate uptake of astrocytes in order to reduce excitotoxicity and provide neuroprotection in models of stroke and ALS.

Other proposed targets related to astrogliosis include manipulating AQP4 channels, diminishing the action of NF-kB, or regulating the STAT3 pathway in order to reduce the inflammatory effects of reactive astrocytes.

[4] Future directions for identifying novel therapeutic strategies must carefully account for the complex array of factors and signaling mechanisms driving the gliosis response, particularly in different stages after damage and in different lesion conditions.