Cell nucleus

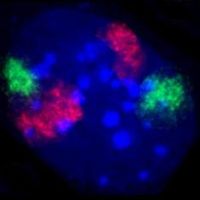

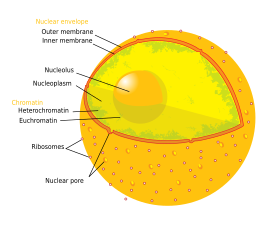

Although the interior of the nucleus does not contain any membrane-bound subcompartments, a number of nuclear bodies exist, made up of unique proteins, RNA molecules, and particular parts of the chromosomes.

[6] Antibodies to certain types of chromatin organization, in particular, nucleosomes, have been associated with a number of autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

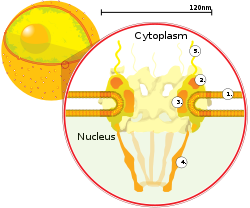

Attached to the ring is a structure called the nuclear basket that extends into the nucleoplasm, and a series of filamentous extensions that reach into the cytoplasm.

[14] Steroid hormones such as cortisol and aldosterone, as well as other small lipid-soluble molecules involved in intercellular signaling, can diffuse through the cell membrane and into the cytoplasm, where they bind nuclear receptor proteins that are trafficked into the nucleus.

Like all proteins, lamins are synthesized in the cytoplasm and later transported to the nucleus interior, where they are assembled before being incorporated into the existing network of nuclear lamina.

[16][17] Lamins found on the cytosolic face of the membrane, such as emerin and nesprin, bind to the cytoskeleton to provide structural support.

[15] Mutations in lamin genes leading to defects in filament assembly cause a group of rare genetic disorders known as laminopathies.

[23] In the first step of ribosome assembly, a protein called RNA polymerase I transcribes rDNA, which forms a large pre-rRNA precursor.

[10]: 328 [24] The transcription, post-transcriptional processing, and assembly of rRNA occurs in the nucleolus, aided by small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA) molecules, some of which are derived from spliced introns from messenger RNAs encoding genes related to ribosomal function.

[24] Speckles are subnuclear structures that are enriched in pre-messenger RNA splicing factors and are located in the interchromatin regions of the nucleoplasm of mammalian cells.

[25] At the fluorescence-microscope level they appear as irregular, punctate structures, which vary in size and shape, and when examined by electron microscopy they are seen as clusters of interchromatin granules.

[37] Unlike CBs, gems do not contain small nuclear ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), but do contain a protein called survival of motor neuron (SMN) whose function relates to snRNP biogenesis.

[49] Paraspeckles sequester nuclear proteins and RNA and thus appear to function as a molecular sponge[51] that is involved in the regulation of gene expression.

They form under high proteolytic conditions within the nucleus and degrade once there is a decrease in activity or if cells are treated with proteasome inhibitors.

[55] These nuclear bodies contain catalytic and regulatory subunits of the proteasome and its substrates, indicating that clastosomes are sites for degrading proteins.

[54] The nucleus provides a site for genetic transcription that is segregated from the location of translation in the cytoplasm, allowing levels of gene regulation that are not available to prokaryotes.

[1]: 509–18 RNA splicing, carried out by a complex called the spliceosome, is the process by which introns, or regions of DNA that do not code for protein, are removed from the pre-mRNA and the remaining exons connected to re-form a single continuous molecule.

The ability of importins and exportins to transport their cargo is regulated by GTPases, enzymes that hydrolyze the molecule guanosine triphosphate (GTP) to release energy.

The key GTPase in nuclear transport is Ran, which is bound to either GTP or GDP (guanosine diphosphate), depending on whether it is located in the nucleus or the cytoplasm.

[64] Specialized export proteins exist for translocation of mature mRNA and tRNA to the cytoplasm after post-transcriptional modification is complete.

In many cells, the centrosome is located in the cytoplasm, outside the nucleus; the microtubules would be unable to attach to the chromatids in the presence of the nuclear envelope.

Changes associated with apoptosis directly affect the nucleus and its contents, for example, in the condensation of chromatin and the disintegration of the nuclear envelope and lamina.

[88] The archaeal origin of the nucleus is supported by observations that archaea and eukarya have similar genes for certain proteins, including histones.

Observations that myxobacteria are motile, can form multicellular complexes, and possess kinases and G proteins similar to eukarya, support a bacterial origin for the eukaryotic cell.

[91] The most controversial model, known as viral eukaryogenesis, posits that the membrane-bound nucleus, along with other eukaryotic features, originated from the infection of a prokaryote by a virus.

The suggestion is based on similarities between eukaryotes and viruses such as linear DNA strands, mRNA capping, and tight binding to proteins (analogizing histones to viral envelopes).

[98] The nucleus was also described by Franz Bauer in 1804[99] and in more detail in 1831 by Scottish botanist Robert Brown in a talk at the Linnean Society of London.

Brown was studying orchids under the microscope when he observed an opaque area, which he called the "areola" or "nucleus", in the cells of the flower's outer layer.

This was in contradiction to Ernst Haeckel's theory that the complete phylogeny of a species would be repeated during embryonic development, including generation of the first nucleated cell from a "monerula", a structureless mass of primordial protoplasm ("Urschleim").

The function of the nucleus as carrier of genetic information became clear only later, after mitosis was discovered and the Mendelian rules were rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century; the chromosome theory of heredity was therefore developed.