Domestication syndrome

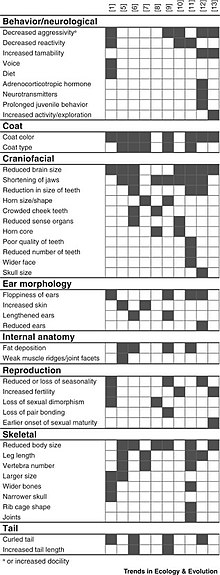

[9][10] Other research[3] suggested that pleiotropic change in neural crest cell regulating genes was the common cause of shared traits seen in many domesticated animal species.

However, several recent publications have either questioned this neural crest cell explanation[4][11][10] or cast doubt on the existence of domestication syndrome itself.

[9] One recent publication[10] points out that shared selective regime changes following transition from wild to domestic environments are a more likely cause of any convergent traits.

Especially in the case of plant crops, doubt has been cast because some domestication traits have been found to result from unrelated loci.

As the differences in these genes could also be found in ancient dog fossils, these were regarded as being the result of the initial domestication and not from recent breed formation.

This trait is influenced by those genes which act in the neural crest, which led to the phenotypes observed in modern dogs.

[27] But, the observation of changed neural crest cell genes between wild and domestic populations need only reveal changes to features derived from neural crest, it does not support the claim of a common underlying genetic architecture that causes all of the domestication syndrome traits in all of the different animal species.

[11] Gleeson and Wilson[10] synthesised this debate and showed that animal domestication syndrome is not caused by selection for tameness, or by neural crest cell genetic pleiotropy.

For example, tamer behaviour might be caused by reduced adrenal reactivity,[31] by increased oxytocin production,[32] or by a combination of these or other mechanisms, across the different populations and species.

In cereals, these include little to no shattering[12]/fruit abscission,[19] shorter height (thus decreased lodging), larger grain[12] or fruit[19] size, easier threshing, synchronous flowering, altered timing of flowering, increased grain weight,[12] glutinousness (stickiness, not gluten protein content),[19][12] increased fruit/grain number, altered color compounds, taste, and texture, daylength independence, determinate growth, lesser/no vernalization, less seed dormancy.

[19] Control of the syndrome traits in cereals is by: Many of these are mutations in regulatory genes, especially transcription factors, which is likely why they work so well in domestication: They are not new, and are relatively ready to have their magnitudes altered.