Go (game)

[17] The name Go is a short form of the Japanese word igo (囲碁; いご), which derives from earlier wigo (ゐご), in turn from Middle Chinese ɦʉi gi (圍棋, Mandarin: wéiqí, lit.

High-level players spend years improving their understanding of strategy, and a novice may play many hundreds of games against opponents before being able to win regularly.

Strategy deals with global influence, the interaction between distant stones, keeping the whole board in mind during local fights, and other issues that involve the overall game.

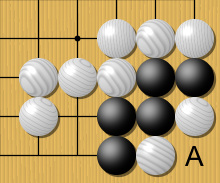

[45] It is possible that one player may succeed in capturing a large weak group of the opponent's, which often proves decisive and ends the game by a resignation.

However, matters may be more complex yet, with major trade-offs, apparently dead groups reviving, and skillful play to attack in such a way as to construct territories rather than kill.

In brief, the middlegame switches into the endgame when the concepts of strategy and influence need reassessment in terms of concrete final results on the board.

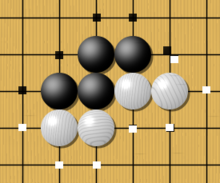

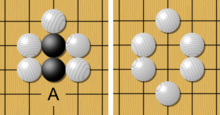

[61] An example of a situation in which the ko rule applies Players are not allowed to make a move that returns the game to the immediately prior position.

If White were allowed to play again on the red circle, it would return the situation to the original one, but the ko rule forbids that kind of endless repetition.

[13] Legends trace the origin of the game to the mythical Chinese emperor Yao (2337–2258 BCE), who was said to have had his counselor Shun design it for his unruly son, Danzhu, to favorably influence him.

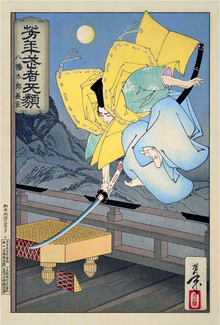

In the same year, he assigned the then-best player in Japan, a Buddhist monk named Nikkai (né Kanō Yosaburo, 1559), to the post of Godokoro (Minister of Go).

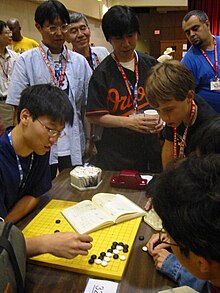

[98] For most of the 20th century, the Japan Go Association (Nihon Ki-in) played a leading role in spreading Go outside East Asia by publishing the English-language magazine Go Review in the 1960s, establishing Go centers in the U.S., Europe and South America, and often sending professional teachers on tour to Western nations.

Although the game was developed in China, the establishment of the Four Go houses by Tokugawa Ieyasu at the start of the 17th century shifted the focus of the Go world to Japan.

State sponsorship, allowing players to dedicate themselves full-time to study of the game, and fierce competition between individual houses resulted in a significant increase in the level of play.

[116] After the end of the Tokugawa shogunate and the Meiji Restoration period, the Go houses slowly disappeared, and in 1924, the Nihon Ki-in (Japanese Go Association) was formed.

[122] In China, the game declined during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) but quickly recovered in the last quarter of the 20th century, bringing Chinese players, such as Nie Weiping and Ma Xiaochun, on par with their Japanese and South Korean counterparts.

His disciple Lee Chang-ho was the dominant player in international Go competitions for more than a decade spanning much of 1990s and early 2000s; he is also credited with groundbreaking works on the endgame.

[127] Several Chinese players also rose to the top in international Go from 2000s, most notably Ma Xiaochun, Chang Hao, Gu Li and Ke Jie.

The natural resources of Japan have been unable to keep up with the enormous demand for the slow-growing Kaya trees; both T. nucifera and T. californica take many hundreds of years to grow to the necessary size, and they are now extremely rare, raising the price of such equipment tremendously.

[132] Other, less expensive woods often used to make quality table boards in both Chinese and Japanese dimensions include Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata), Katsura (Cercidiphyllum japonicum), Kauri (Agathis), and Shin Kaya (various varieties of spruce, commonly from Alaska, Siberia and China's Yunnan Province).

The material comes from Yunnan Province and is made by sintering a proprietary and trade-secret mixture of mineral compounds derived from the local stone.

This process dates to the Tang dynasty and, after the knowledge was lost in the 1920s during the Chinese Civil War, was rediscovered in the 1960s by the now state-run Yunzi company.

Go long posed a daunting challenge to computer programmers, putting forward "difficult decision-making tasks, an intractable search space, and an optimal solution so complex it appears infeasible to directly approximate using a policy or value function".

In March 2016, Google next challenged Lee Sedol, a 9 dan considered the top player in the world in the early 21st century,[151] to a five-game match.

[160] In February 2023, Kellin Pelrine, an amateur American Go player, won 14 out of 15 games against a top-ranked AI system in a significant victory over artificial intelligence.

[q] Apart from technical literature and study material, Go and its strategies have been the subject of several works of fiction, such as The Master of Go by Nobel Prize in Literature-winning author Yasunari Kawabata[r] and The Girl Who Played Go (2001) by Shan Sa.

[167][168] Similarly, Go has been used as a subject or plot device in film, such as Pi (π), A Beautiful Mind, Tron: Legacy, Knives Out, and The Go Master (a biopic of Go professional Go Seigen).

A 2004 review of literature by Fernand Gobet, de Voogt and Jean Retschitzki showed that relatively little scientific research had been carried out on the psychology of Go, compared with other traditional board games such as chess.

According to the review of Gobet and colleagues, the pattern of brain activity observed with techniques such as PET and fMRI does not show large differences between Go and chess.

[182] Arthur Mary, a French researcher in clinical psychopathology, reports on his psychotherapeutic approaches using the game of Go with patients in private practice and in a psychiatric ward.

Other game theoretical taxonomy elements include the facts In the endgame, it can often happen that the state of the board consists of several subpositions that do not interact with the others.