Goldberg Variations

... Once the Count mentioned in Bach's presence that he would like to have some clavier pieces for Goldberg, which should be of such a smooth and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights.

Bach thought himself best able to fulfill this wish by means of Variations, the writing of which he had until then considered an ungrateful task on account of the repeatedly similar harmonic foundation.

Nevertheless, even had the gift been a thousand times larger, their artistic value would not yet have been paid for.Forkel wrote his biography in 1802, more than 60 years after the events related, and its accuracy has been questioned.

Goldberg's age at the time of publication (14 years) has also been cited as grounds for doubting Forkel's tale, although it must be said that he was known to be an accomplished keyboardist and sight-reader.

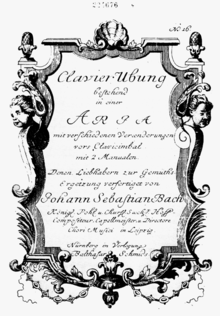

The title page, shown in the figure above, reads in German: The term "Clavier Ubung" (nowadays spelled "Klavierübung") had been assigned by Bach to some of his previous keyboard works.

Of these, the most valuable is the Handexemplar (Bach's personal copy of the published score),[5] discovered in 1974 in Strasbourg by the French musicologist Olivier Alain and now kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

This copy includes printing corrections made by the composer and additional music in the form of fourteen canons on the Goldberg ground (see below).

The nineteen printed copies provide virtually the only information available to modern editors trying to reconstruct Bach's intent, as the autograph (handwritten) score has not survived.

Christoph Wolff suggests on the basis of handwriting evidence that Anna Magdalena copied the aria from the autograph score around 1740; it appears on two pages previously left blank.

The variations found just after each canon are genre pieces of various types, among them three Baroque dances (4, 7, 19); a fughetta (10); a French overture (16); two ornate arias for the right hand (13, 25); and others (22, 28).

This is a simple three-part contrapuntal piece in 24 time, two voices engage in constant motivic interplay over an incessant bass line.

A rapid melodic line predominantly in sixteenth notes is accompanied by another melody with longer note values, which features very wide leaps: The Italian type of hand-crossing such as is frequently found in the sonatas of Scarlatti is employed here, with one hand constantly moving back and forth between high and low registers while the other hand stays in the middle of the keyboard, playing the fast passages.

In his book The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach[9] the scholar and keyboardist David Schulenberg notes that the discovery "surprised twentieth-century commentators who supposed gigues were always fast and fleeting."

The French style of hand-crossing such as is found in the clavier works of François Couperin is employed, with both hands playing at the same part of the keyboard, one above the other.

Variation 10 is a four-voice fughetta, with a four-bar subject heavily decorated with ornaments and somewhat reminiscent of the opening aria's melody.

Pianist Angela Hewitt notes that there is "a wonderful effect at the very end [of this variation]: the hands move away from each other, with the right suspended in mid-air on an open fifth.

It's a piece so moving, so anguished—and so uplifting at the same time—that it would not be in any way out of place in the St. Matthew's Passion; matter of fact, I've always thought of Variation 15 as the perfect Good Friday spell.

"[10] The entire set of variations can be seen as being divided into two halves, clearly marked by this grand French overture, commencing with particularly emphatic opening and closing chords.

Here Bach follows his custom of beginning the second half of a major collection with a movement in French style, as with the earlier Clavier-Übung volumes, in both parts of the Well-Tempered Clavier, in the Musical Offering (#4 of the numbered canons) and in the early version of the Art of Fugue (#7 of P 200).

Nicholas Kenyon calls Variation 18 "an imperious, totally confident movement which must be among the most supremely logical pieces of music ever written, with the strict imitation to the half-bar providing ideal impetus and a sense of climax.

[13] The bass line here is one of the most eloquent found in the variations, to which Bach adds chromatic intervals that provide tonal shadings.

[16] Williams writes that "the beauty and dark passion of this variation make it unquestionably the emotional high point of the work",[17] and Glenn Gould said that "the appearance of this wistful, weary cantilena is a master-stroke of psychology.

"[10] In sharp contrast with the introspective and passionate nature of the previous variation, this piece is another virtuosic two-part toccata, joyous and fast-paced.

Following this is a section with both hands playing in contrary motion in a melodic contour marked by sixteenth notes (bars 9–12).

[21] For example, part of Variation 30 traces back to the melody of the Italian Bergamask dance,[19] which not only gave rise to compositions by many musicians (such as Dieterich Buxtehude, under the title of La Capricciosa, for his thirty-two partite in G major, BuxWV 250[22]), but is even sung to various words in regions such as Iceland today.

[23] A handwritten note found in a collector's copy of the Clavier Ubung claims that Bach's student, Johann Christian Kittel, identified two folk tunes making up Variation 30 by their first lines.

Today, the identity of "Kraut und Rüben..." is uncontroversial, since multiple versions of the text, including some explicitly set to the Bergamask theme, are preserved.

Its melody is made to stand out by what has gone on in the last five variations, and it is likely to appear wistful or nostalgic or subdued or resigned or sad, heard on its repeat as something coming to an end, the same notes but now final.

"[27] When Bach's personal copy of the printed edition of the Goldberg Variations (see above) was discovered in 1974, it was found to include an appendix in the form of fourteen canons built on the first eight bass notes from the aria.

According to the art critic Michael Kimmelman, "Busoni shuffled the variations, skipping some, then added his own rather voluptuous coda to create a three-movement structure; each movement has a distinct, arcing shape, and the whole becomes a more tightly organized drama than the original.