Weimar concerto transcriptions (Bach)

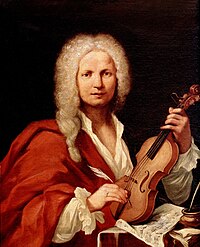

Bach transcribed for organ and harpsichord a number of Italian and Italianate concertos, mainly by Antonio Vivaldi, but with others by Alessandro Marcello, Benedetto Marcello, Georg Philipp Telemann and the musically talented Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar.

Peters in the 1850s and by Breitkopf & Härtel in the 1890s played a decisive role in the Vivaldi revival of the twentieth century.

The pleasure His Grace took in his playing fired him with the desire to try every possible artistry in his treatment of the organ.Bach's concerto transcriptions reflect not only his general interest in and assimilation of musical forms originating in Italy, in particular the concertos of his Venetian contemporary Antonio Vivaldi, but also the particular circumstances of his second period of employment 1708–1717 at the court in Weimar.

A talented amateur musician, from an early age Prince Johann Ernst had been taught the violin by the court violinist Gregor Christoph Eilenstein.

The first documented evidence of Bach's engagement with the concerto genre can be dated to around 1709, during his second period in Weimar, when he made a hand copy of the continuo part of Albinoni's Sinfonie e concerti a 5, Op.

Earlier compositions had been brought back to Weimar from Italy by the deputy Capellmeister, Johann Wilhelm Drese, during his stay there in 1702–1703.

In 1709 the virtuoso violinist Johann Georg Pisendel visited Weimar: he had studied with Torelli and is likely to have acquainted Bach with more of the Italian concerto repertoire.

In the same year Bach also copied out all the parts of the double violin concerto in G major, TWV 52:G2, of Georg Philipp Telemann, a work that he might have acquired through Pisendel.

A keen amateur violinist, he is likely to have brought or sent back concerto scores from Amsterdam, probably including the collection L'estro armonico, Op.

In July 1714, however, poor health forced him to leave Weimar to seek medical treatment in Bad Schwalbach: he died a year later at the age of nineteen.

At the same time, Bach's cousin Walther also made a series of organ transcriptions of Italian concertos: in his autobiography, Walther mentions 78 such transcriptions; but of these only 14 survive, of concertos by Albinoni, Giorgio Gentili, Giulio Taglietti, Telemann, Torelli and Vivaldi.

[12] Schulze (1978) has given the following explanation for the transcriptions:[13] Bach’s organ and harpsichord transcriptions BWV 592–596 and 972–987 belong to the year July 1713 to July 1714, were made at the request of Prince Johann Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar, and imply a definite connection with the concert repertory played in Weimar and enlarged by the Prince’s recent purchases of music.

Since the court concerts gave Bach an opportunity to know the works in their original form, the transcriptions are not so much study-works as practical versions and virtuoso 'commissioned' music.Schulze has further suggested that during his two year period studying in the Netherlands, Prince Johann Ernst is likely to have attended the popular concerts in the Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam where the blind organist Jan Jakob de Graaf performed his own transcriptions of the most recent Italian concertos.

It is possible that this could have led to Johann Ernst to suggest similar concerto transcriptions to Bach and Walther.

Other circumstantial evidence concerning music-making in Weimar is provided by a letter written by Bach's pupil Philipp David Kräuter in April 1713.

Asking for permission to stay longer in Weimar, he states that Prince Johann Ernst, who himself plays the violin incomparably, will return to Weimar from Holland after Easter and spend the summer here; I could then hear much fine Italian and French music, which would be particularly profitable to me in composing concertos and ouvertures ...

The Nekrolog contains the famous statement about the Duke, Wilhelm Ernst, encouraging Bach as an organist-composer, quoted at the start of this section.

Most beginning composers let their fingers run riot up and down the keyboard, snatching handfuls of notes, assaulting the instrument in an undisciplined way ...

Moreover, in adapting ideas and figurations originally conceived for the violin to the keyboard, Bach was compelled to think in musical terms, so that his ideas no longer depended on his fingers, but were drawn from his imagination.Although Forkel's account is generally acknowledged to be oversimplified and factually inaccurate, commentators agree that Bach's knowledge and assimilation of the Italian concerto form—which happened partly through his transcriptions—played a key role in the development of his mature style.

In practical terms, the concerto transcriptions were suitable for performance in the different venues in Weimar; they would have served an educational purpose for the young prince as well as giving him pleasure.

[16] Marshall (1986) has carried out a systematic study of headings and markings in surviving manuscripts to ascertain the intended instrument for Bach's keyboard works.

Based on known manualiter settings within Bach's works for organ, the possible audience for performances of virtuosic keyboard compositions and the circumstances of their composition, Marshall has suggested that the concerto transcriptions BWV 972–987 might originally have been intended as manualiter settings for the organ.

More significantly perhaps, the concerto transcriptions played a decisive role in the Vivaldi revival which happened only in the following century.

The meteoric success of Vivaldi in the early eighteenth century was matched by his descent into almost complete oblivion soon after his death in 1741.

In Great Britain, France and particularly his native Italy, musical taste turned against him and, when he was remembered, it was just through salacious anecdote.

The remaining organ transcriptions come from copies made in Leipzig by Bach's family and circle: these include his eldest son Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, whose organ repertoire included the transcriptions; his pupil Johann Friedrich Agricola; and Johann Peter Kellner.

Despite the fact that Carl Friedrich Zelter, director of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin where many Bach manuscripts were held, had suggested Johann Sebastian as the author, the transcription was first published as a work by Wilhelm Friedemann in 1844 in the edition prepared for C.F.

As explained in Williams (2003), their main purpose was to enable the concerto to be heard at Bach's desired pitch.

The markings are also significant for what they show about performance practise at that time: during the course of a single piece, hands could switch manuals and organ stops could be changed.

[21][22][23] [c] After a concerto by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar, and Bach's earlier organ transcription, BWV 592.