Golden Square Mile

[2] By the 1930s, multiple factors led to the neighbourhood's decline, including the Great Depression, the dawn of the automobile, the demand for more heat-efficient houses, and the younger generations of the families that had built these homes having largely moved to Westmount.

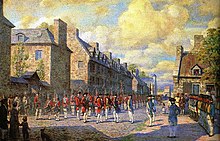

As many of the wealthy French Canadians moved from Canada to France following the Conquest, British merchants were able to cheaply purchase vast tracts of land upon which to build factories, and take control of the banking and finance of the new Dominion.

For decades, the wealth accumulated from the fur trade, finance, and other industries made of Montreal's mercantile elite a "kind of commercial aristocracy, living in lordly and hospitable style," as Washington Irving observed.

[9] In 1820, John Bigsby penned his impressions of the city:I found, but did not expect to find, at Montreal a pleasing transcript of the best form of London life — even in the circle beneath the very first class of official families.

The wealthy merchants in particular began to seek large plots of land on which to build homes worthy of their success while remaining close to their business interests; and, their eyes turned to the fertile farmland under Mount Royal.

John Duncan observed in 1818 that, "a number of very splendid mansions have lately been erected on the slope of the mountain, which would be regarded as magnificent residences even by the wealthy merchants of the mother country".

[14] In 1820, John Bigsby described the view from Château St. Antoine, then said to be 'the most magnificent building in the whole city and standing within 200 acres of parkland roughly at the end of Dorchester Street: I had the pleasure of dining with (William McGillivray) at his seat, on a high terrace under the mountain, looking southwards and laid out in pleasure-grounds in the English style.

Close beneath you are scattered elegant country retreats embowered in plantations, succeeded by a crowd of orchards of delicious apples, spreading far to the right and left, and hedging in the glittering churches, hotels, and house-roofs of Montreal...[15]The early residents of the Square Mile enjoyed marked benefits from being the first to settle there: The houses were surrounded by acres of parkland, with long carriage drives, vineries, orchards, fruit and vegetable gardens.

[16] The surveyor Joseph Bouchette noted that the produce from these gardens in the summer months was "excellent in quality, affording a profuse supply... in as much, or even greater perfection than in many southern climes".

[28] The city's lively reputation had not diminished, as Charles Goodrich suggested with a hint of disapproval: "If you wish to enjoy good eating, dancing, music and gayety, you will find an abundance of all (at Montreal)".

It seems difficult to understand how such a fire could have lasted so long a time and have done so much mischief, as the houses were not built of wood, which I had always imagined to be the case.. (We visited) a most beautiful and wonderful garden, belonging to a Montreal merchant (probably John Torrance of St. Antoine Hall), whose name I forget but who has collected here everything which is rich and rare, in shrub or flower.

He purchased fourteen acres from the decaying McTavish estate and built a sumptuous home of 72 rooms that excelled "in size and cost any dwelling-house in Canada," surpassing Dundurn Castle.

[31] In 1878, the Marquis of Lorne and Princess Louise were posted to Canada as the new Vice-regal couple, while Montreal was attracting celebrities of the day such as Charles Dickens, Rudyard Kipling, Mark Twain and Abraham Lincoln.

Celebrating their success, they spared no expense on their homes, with interiors decked in detailed mahogany and private art galleries housing works of the likes of Raphael, Rembrandt, Cézanne, Constable and Gainsborough etc.

As an Englishman, previously well travelled in France, Italy, Germany, Switzerland and Spain, he paid a high complement to "this flourishing and wealthy city" when he stated that, "upon the whole, I prefer Montreal, as a place of residence, to almost any town that I have ever seen."

There is a great absence of poverty, except perhaps among the lowest French population.. Happily there is at present (1871) a kindly feeling between the Roman Catholics and Protestants, each pursuing their own course without molesting the other.

There is perhaps a little too much expense devoted to them; and this prevents all but the wealthy from indulging in such hospitalities.The Upper parts of the town are of more recent growth, and contain commodious and detached houses, belonging to the men of business and persons of fortune.

Taken all in all, there is perhaps no wealthier city area in the world than that comprised between Beaver Hall Hill and the foot of Mount Royal, and between the parallel lines of Dorchester and Sherbrooke Streets in the West End.

Giving an estimated $100 million to charity in his lifetime, McConnell followed in the magnanimous steps of some of Montreal's best remembered philanthropists, such as Lord Strathcona, to whom King Edward VII referred as "Uncle Donald" in recognition of his generosity towards charitable causes across the British Empire.

"The Union Jack flew from Ravenscrag (since inherited by Sir Montague Allan)"[53] where the Montreal Hunt now met, and Lady Drummond was heard to reflect the sentiments of the Square Mile by stating, "the Empire is my country.

The British Prime Minister David Lloyd George claimed to his biographer that had the war continued into 1919, he would have sought to replace Field Marshal Douglas Haig with the Square Mile's General Sir Arthur Currie.

[62] Similarly to the Canadiens of the Ancien Régime a century before, the Square Milers with their old-fashioned British ideals and business principles did not adapt to the changes in society and held themselves aloof.

Newcomers, who neither knew nor cared about the old guard and their traditions were more often than not barred from entry into Square Mile society (such as membership to Montreal's most prestigious men's club, the Mount Royal), but this only served to further alieniate the declining enclave.

Those who had relied on investments moved to smaller, more heat-efficient houses in Westmount or took apartments at the Ritz-Carlton Montreal, whereas others like Sir Herbert Samuel Holt, who never dealt on margin, emerged untouched.

The social divide between anglophones employers and French Canadian workers in Quebec had existed for a long time, but the economic turmoil of the Great Depression led to calls for change from the status quo.

This law, the election of the PQ, and the threat of Quebec independence caused instability in the province's business environment, and accelerated the move of some companies' headquarters from Montreal to other Canadian cities, including Calgary and Toronto.

Angus and an heir as the grand-niece of Lord Mount Stephen, has been fighting to maintain not just the wishes but the conditions set down by the founders to the city, and find use for the land and its buildings as a research facility.

In 2002, following intervention by Heritage Montreal, Projet Montréal and local citizens, the Commission d'arbitrage de la Ville de Montréal refused the demolition permit granted by the Bourque administration, on the grounds of the solidity of the house and reminding the owner of his obligation to keep it in good condition—the Sochaczevski family had signed an agreement with the Montreal City Council to maintain the house when they bought it in 1986, but did nothing to maintain, protect or stabilize it.

[43][69] As a mayoral candidate, Gérald Tremblay portrayed himself as a defender of the Redpath house and heritage buildings, but as soon as he gained office—strongly backed by The Suburban newspaper, owned by the Sochaczevski family—he considered a plan to allow demolition to continue.

After these talks with the owner, Kotto concluded that Redpath House "does not present a national heritage interest," and gave the go ahead for it to be torn down to make for way for the promoter's development.