Gone with the Wind (film)

Although the film has been criticized as historical negationism, glorifying slavery and the Lost Cause of the Confederacy myth, it has been credited with triggering changes in the way in which African Americans were depicted cinematically.

Unable to pay the Reconstructionist taxes imposed on Tara, Scarlett unsuccessfully appeals to Rhett, then dupes her younger sister Suellen's fiancé, the middle-aged and wealthy general store owner Frank Kennedy, into marrying her.

When Rhett returns from an extended trip to London, England, Scarlett informs him that she is pregnant, but an argument ensues, resulting in her falling down a flight of stairs and suffering a miscarriage.

[3] Early frontrunners included Miriam Hopkins and Tallulah Bankhead, who were regarded as possibilities by Selznick prior to the purchase of the film rights; Joan Crawford, who was signed to MGM, was also considered as a potential pairing with Gable.

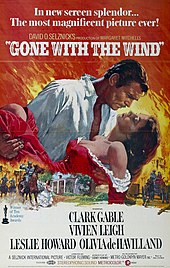

[6][7][8] Many actresses, both known and unknown, were considered, but only thirty, in addition to the eventual choice, Vivien Leigh, were actually tested for the role, including Ardis Ankerson (Brenda Marshall), Jean Arthur, Tallulah Bankhead, Diana Barrymore, Joan Bennett, Nancy Coleman, Frances Dee, Terry Ray (Ellen Drew), Paulette Goddard, Edythe Marrenner (Susan Hayward), Anita Louise, Haila Stoddard, Margaret Tallichet, Lana Turner, and Linda Watkins.

[22][23] Vivien Leigh and Olivia de Havilland learned of Cukor's firing on the day the Atlanta bazaar scene was filmed, and the pair went to Selznick's office in full costume and implored him to change his mind.

[27][nb 5] Although legend persists that the Hays Office fined Selznick $5,000 for using the word "damn" in Butler's exit line, in fact, the Motion Picture Association board passed an amendment to the Production Code on November 1, 1939, that forbade the use of the words "hell" or "damn" except when their use "shall be essential and required for portrayal, in proper historical context, of any scene or dialogue based upon historical fact or folklore ... or a quotation from a literary work, provided that no such use shall be permitted which is intrinsically objectionable or offends good taste".

Due to the pressure of completing on time, Steiner received some assistance in composing from Friedhofer, Deutsch, and Heinz Roemheld, and in addition, two short cues—by Franz Waxman and William Axt—were taken from scores in the MGM library.

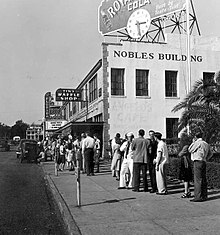

It was the climax of three days of festivities hosted by Mayor William B. Hartsfield, which included a parade of limousines featuring stars from the film, receptions, thousands of Confederate flags, and a costume ball.

[27][33] Hattie McDaniel was also absent, as she and the other black cast members were prevented from attending the premiere due to Georgia's Jim Crow laws, which kept them from sitting with their white colleagues.

[53] The Manchester Guardian felt that the film's one serious drawback was that the story lacked the epic quality to justify the outlay of time and found the second half, which focuses on Scarlett's "irrelevant marriages" and "domestic squabbles", mostly superfluous, and the sole reason for their inclusion had been "simply because Margaret Mitchell wrote it that way".

The Guardian believed that if "the story had been cut short and tidied up at the point marked by the interval, and if the personal drama had been made subservient to a cinematic treatment of the central theme—the collapse and devastation of the Old South—then Gone With the Wind might have been a really great film".

[51] Similarly, Hoellering found her "perfect" in "appearance and movements"; he felt her acting best when she was allowed to "accentuate the split personality she portrays" and thought she was particularly effective in such moments of characterization like the morning after the marital rape scene.

Moss further called out the stereotypical black characterizations, such as the "shiftless and dull-witted Pork", the "indolent and thoroughly irresponsible Prissy", Big Sam's "radiant acceptance of slavery", and Mammy with her "constant haranguing and doting on every wish of Scarlett".

At the Capitol Theatre in New York alone, it averaged eleven thousand admissions per day in late December,[36] and within four years of its release had sold an estimated sixty million tickets across the United States—sales equivalent to just under half the population at the time.

[37][72] Successful re-releases in 1954 and 1961 enabled it to retain its position as the industry's top earner, despite substantial challenges from more recent films such as Ben-Hur,[76] but it was finally overtaken by The Sound of Music in 1966.

[72][79] Including its $6.7 million rental from the 1961 reissue,[80] it was the fourth highest-earner of the decade in the North American market, with only The Sound of Music, The Graduate and Doctor Zhivago making more for their distributors.

[83][84][85] The film's appeal has endured overseas, sustaining a popularity similar to its domestic longevity; in 1975 it played to capacity audiences every night during the first three weeks of its run at London's Plaza 2 Theatre, and in Japan it generated over half a million admissions at twenty theaters during a five-week engagement.

[92][93] Schickel also believes the film fails as popular art in that it has limited rewatch value—a sentiment that Kauffmann also concurs with, stating that having watched it twice he hopes "never to see it again: twice is twice as much as any lifetime needs".

[95] Judith Crist observes that, kitsch aside, the film is "undoubtedly still the best and most durable piece of popular entertainment to have come off the Hollywood assembly lines", the product of a showman with "taste and intelligence".

[92] Kauffmann also finds interesting parallels with The Godfather, which had just replaced Gone with the Wind as the highest-grosser at the time: both were produced from "ultra-American" best-selling novels, both live within codes of honor that are romanticized, and both in essence offer cultural fabrication or revisionism.

Reynolds likened Gone with the Wind to The Birth of a Nation and other re-imaginings of the South during the era of segregation, in which white Southerners are portrayed as defending traditional values, and the issue of slavery is largely ignored.

One such viewpoint is reflected in a brief scene in which Mammy fends off a leering freedman: a politician can be heard offering forty acres and a mule to the emancipated slaves in exchange for their votes.

[112] Richard Alleva remarks that, in the film, "a black man merely restrains Scarlett's horse while his white companion (in a memorable close-up) lowers his leering face toward the unconscious heroine; soon a faithful former slave appears and fights off both attackers.

"[114] Cripps also quotes a memorandum written by Selznick: "I personally feel quite strongly that we should cut out the Klan entirely ... [otherwise, the film] might come out as an unintentional advertisement for intolerant societies in these fascist-ridden times."

It was also announced that the film would return to the streaming service at a later date, although it would incorporate "a discussion of its historical context and a denouncement of those very depictions, but will be presented as it was originally created because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed.

[124] Stewart described the film, in an op-ed for CNN, as "a prime text for examining expressions of white supremacy in popular culture", and said that "it is precisely because of the ongoing, painful patterns of racial injustice and disregard for Black lives that Gone with the Wind should stay in circulation and remain available for viewing, analysis and discussion".

[129] The scene has been accused of combining romance and rape by making them indistinguishable from each other,[129] and of reinforcing a notion about forced sex: that women secretly enjoy it, and it is an acceptable way for a man to treat his wife.

[132] Gone with the Wind and its production have been explicitly referenced, satirized, dramatized, and analyzed on numerous occasions across a range of media, from contemporaneous works such as Second Fiddle—a 1939 film spoofing the "search for Scarlett"—to current television shows, such as The Simpsons.

Edwards submitted a 775-page manuscript which was titled Tara, The Continuation of Gone with the Wind, set between 1872 and 1882 and focusing on Scarlett's divorce from Rhett; MGM was not satisfied with the story, and the deal collapsed.