Imperial examination

In addition to Asia, reports by European missionaries and diplomats introduced the Chinese examination system to the Western world and encouraged France, Germany and the British East India Company (EIC) to use similar methods to select prospective employees.

Although some examinations did exist from the Han to the Sui dynasty, they did not offer an official avenue to government appointment, the majority of which were filled through recommendations based on qualities such as social status, morals, and ability.

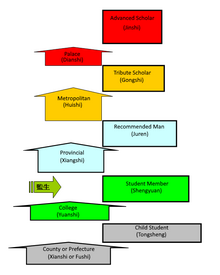

During the Song dynasty the emperors expanded both examinations and the government school system, in part to counter the influence of military aristocrats, increasing the number of degree holders to more than four to five times that of the Tang.

However the examinations co-existed with other forms of recruitment such as direct appointments for the ruling family, nominations, quotas, clerical promotions, sale of official titles, and special procedures for eunuchs.

Wu lavished favors on the newly graduated jinshi degree-holders, increasing the prestige associated with this path of attaining a government career, and clearly began a process of opening up opportunities to success for a wider population pool, including inhabitants of China's less prestigious southeast area.

[13] Wu Zetian's government further expanded the civil service examination system by allowing certain commoners and gentry previously disqualified by their non-elite backgrounds to take the tests.

Wu's progressive accumulation of political power through enhancement of the examination system involved attaining the allegiance of previously under-represented regions, alleviating frustrations of the literati, and encouraging education in various locales so even people in the remote corners of the empire would study to pass the imperial exams.

[34] During the early years of the Tang restoration, the following emperors expanded on Wu's policies since they found them politically useful, and the annual averages of degrees conferred continued to rise.

With the upheavals which later developed and the disintegration of the Tang empire into the "Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period", the examination system gave ground to other traditional routes to government positions and favoritism in grading reduced the opportunities of examinees who lacked political patronage.

[41] Prominent officials who went through the imperial examinations include Wang Anshi, who proposed reforms to make the exams more practical, and Zhu Xi (1130–1200), whose interpretations of the Four Classics became the orthodox Neo-Confucianism which dominated later dynasties.

Other special examinations for household and family member of officials, Minister of Personnel, and subjects such as history as applied to current affairs (shiwu ce, Policy Questions), translation, and judicial matters were also administered by the state.

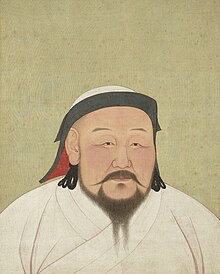

[49] Also, Kublai was opposed to such a commitment to the Chinese language and to the ethnic Han scholars who were so adept at it, as well as its accompanying ideology: he wished to appoint his own people without relying on an apparatus inherited from a newly conquered and sometimes rebellious country.

For example, in 1688, a candidate from Hangzhou who was able to answer policy questions at the palace examination in both Chinese and Manchu was appointed as compiler at the Hanlin Academy, despite finishing bottom of the second tier of jinshi graduates.

[61] The Chinese Christian Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was created in rebellion against the Qing dynasty led by a failed examination candidate Hong Xiuquan, which established its capital in Nanjing in 1851.

Since the entire upper echelon of the Song dynasty was filled by jinshi, and imperial clan members were barred from posts of substance,[75] there was no longer any conflict of the type relating to different preparatory backgrounds.

Some have suggested that limiting the topics prescribed in examination system removed the incentives for Chinese intellectuals to learn mathematics or to conduct experimentation, perhaps contributing to the Great Divergence, in which China's scientific and economic development fell behind Europe.

[102] British and French civil service examinations adopted in the late 19th century were also heavily based on Greco-Roman classical subjects and general cultural studies, as well as assessing personal physique and character.

The examination system distributed its prizes according to provincial and prefectural quotas, which meant that imperial officials were recruited from the whole country, in numbers roughly proportional to each province's population.

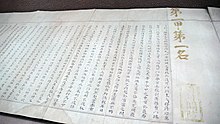

[120] Exact quotes from the classics were required; misquoting even one character or writing it in the wrong form meant failure, so candidates went to great lengths to bring hidden copies of these texts with them, sometimes written on their underwear.

[121][full citation needed] The Minneapolis Institute of Arts holds an example of a Qing dynasty cheatsheet, a handkerchief with 10,000 characters of Confucian classics in microscopically small handwriting.

While he is wondering when the results will be announced and waiting to learn whether he passed or failed, so nervous that he is startled even by the rustling of the trees and the grass and is unable to sit or stand still, his restlessness is like that of a monkey on a leash.

Lower ranked graduates could be appointed to offices like Hanlin bachelor, secretaries, messengers in the Ministry of Rites, case reviewers, erudites, prefectural judges, prefects or county magistrates (zhixian 知縣).

Even just memorizing the reduced portion of the classics was too difficult for most military examinees, who resorted to cheating and bringing with them miniature books to copy, a behavior the examiners let slide owing to the greater weighting of the first two sessions.

The Korean Gugyeol and Japanese Kanbun Kundoku writing systems modified the Chinese text with markers and annotations to represent their respective languages' pronunciation and grammatical order.

[164] Owing to the shared literary and philosophical traditions rooted in Confucian and Buddhist texts and the use of the same script, a large number of Chinese words were borrowed into Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese (KJV).

[165] During the Tang dynasty, a poetry section was added to the examinations, requiring the examinee to compose a shi poem in the five-character, 12-line regulated verse form and a fu composition of 300 to 400 characters.

[169][170][incomplete short citation] Traditional beliefs about fate, that cosmic forces predestine certain human affairs, and particularly that individual success or failure was subject to the will of Heaven and the influence and intervention by various deities, played into the interpretation of results when taking the tests.

During the 18th century, the imperial examinations were often discussed in conjunction with Confucianism, which attracted great attention from contemporary European thinkers such as Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Voltaire, Montesquieu, Baron d'Holbach, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and Friedrich Schiller.

Both Thomas Babington Macaulay, who was instrumental in passing the Saint Helena Act 1833, and Stafford Northcote, 1st Earl of Iddesleigh, who prepared the Northcote–Trevelyan Report that catalyzed the British civil service, were familiar with Chinese history and institutions.

In the People's Republic of China (PRC), the revolutionary government of Mao Zedong rejected the imperial examination system in favor of cadres chosen for loyalty to the ruling Communist Party.