Gorgonopsia

Gorgonopsia (from the Greek Gorgon, a mythological beast, and óps 'aspect') is an extinct clade of sabre-toothed therapsids from the Middle to the Upper Permian, roughly between 270 and 252 million years ago.

Gorgonopsians rose to become apex predators of their environments following the Capitanian mass extinction event which killed off the dinocephalians and some large therocephalians after the Middle Permian.

Gorgonopsian genera are all very similar in appearance, and consequently many species have been named based on flimsy and likely age-related differences since their discovery in the late 19th century, and the group has been subject to several taxonomic revisions.

In 1984, British palaeontologists Doris and Kenneth Kermack suggested that the canines grew to match the size of the skull, and continually broke off until the animal stopped growing, and that gorgonopsians featured an early version of finite tooth replacement exhibited in many mammals.

Like other early synapsids, gorgonopsians have a single occipital condyle, and the articulation (the joints) of the cervical vertebrae is overall reptilian, permitting side-to-side movement of the head but restricting up-and-down motion.

Nonetheless, the dorsals equating to that series are similar to the lumbars of sabre-toothed cats with steeply oriented zygopophases, useful in stabilising the lower back especially when pinning down struggling prey.

The fossil material, although thin, is described in 2022 by paleontologists Jun Liu and Wan Yiang and confirms that it comes from a gorgonopsian dating from the Upper Permian that actually lived in present-day China.

Nominal species are distinguished predominantly by traits which are known to be quite variable depending on the age of the individual, including eye orbit size, snout length, and number of postcanine teeth.

[29] Among the first attempts to organise the clade was carried out by British zoologist David Meredith Seares Watson and American palaeontologist Alfred Romer in 1956, who split it into twenty families, of which the members of three (Burnetiidae, Hipposauridae, and Phthinosuchidae) are not considered gorgonopsians anymore.

[34] Nochnitsa Viatkogorgon Suchogorgon Sauroctonus Pravoslavlevia Inostrancevia Phorcys Eriphostoma Gorgonops Cynariops Lycaenops Smilesaurus Arctops Arctognathus Aelurognathus Ruhuhucerberus Sycosaurus Leontosaurus Dinogorgon Rubidgea Clelandina Synapsida has traditionally been split into the basal "Pelycosauria" and the derived Therapsida.

[35] Sphenacodontidae Biarmosuchia Dinocephalia Anomodontia Gorgonopsia Therocephalia Cynodontia The oldest definitive gorgonopsian fossil worldwide comes from the Port des Canonge Formation of Mallorca in the western Mediterranean.

By the Middle Permian, the equatorial forests had switched to a seasonal wet/dry system, but the swamps were connected to the temperate zones via coastal passages along East Pangaea, allowing cross-continental migration from what is now South Africa to what is now Russia.

Gorgonopsian taxa did coexist with each other—as many as seven at one time—and the fact that some rubidgeines possess postcanines while some other contemporary ones do not suggests that they practiced niche partitioning and pursued different prey items.

[37] It has alternatively been suggested (first in 2002 by biologists Blaire Van Valkenburgh and Tyson Secco, though in reference to cats) that sabres evolved primarily due to sexual selection as a form of mating display.

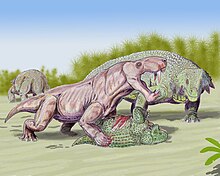

[38] Among the dirk-toothed cats, these predators are suggested to have killed with a well-placed slash to the throat after grappling prey, but gorgonopsians may have been less precise with bite placement, armed with reptilian jaws and tooth arrangements.

Mammalian carnivores, including sabre-toothed cats, instead rely mainly on the "Static-Pressure system" (SP) where the temporalis and masseter muscles produce a strong bite force to kill prey.

The medium-size Arctognathus had a box-like skull and resultantly powerful snout, which would have allowed strong bending and torsion movements, and a combination of both KI and SP bite elements.

Even bigger gorgonopsians, such as Arctops, had a shorter and more convex snout like the earlier sphenecodont Dimetrodon, and would have been able to rapidly clamp the jaws shut from a wide gape (which would have been necessary given the long canines).

If the angle was on the lower end, this would have been a rather firm joint, allowing the deltoids to exert great force through the forelimb, such as when pinning down struggling prey, or holding down a carcass while ripping off flesh.

If the humerus was positioned at a higher angle, this could have permitted enhanced extension forwards and backwards (along the long axis) and thus greater stride length, useful in an attack or short chases.

[37] Gorgonopsians had rather nimble digits, indicative of grasping capability for both the hands and feet, possibly for grappling struggling prey to prevent excessive load bearing on, and consequential fracturing or breaking of, the canines while they were sunk into the victim.

[13] Unlike eutheriodonts, but like some ectothermic creatures today, all gorgonopsians possessed a pineal eye on the top of the head, which is used to detect daylight (and thus, the optimal temperature to be active).

It is possible that other theriodonts lost this due to the evolution of either endothermy, intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells in the eyes—in tandem with the loss of colour vision and a shift to nocturnal life—or both.

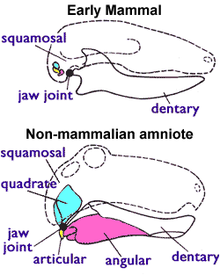

[3] A major anatomical shift occurred between earlier pelycosaurs and therapsids, which is postulated to have been related to an increasing metabolism and the origins of homeothermy (maintenance of a high body temperature).

[48] Among therapsids, only eutheriodonts (not gorgonopsians) have respiratory nasal turbinates, which help retain moisture while breathing in large quantities of air, and its evolution is typically associated with the beginning of "mammalian" oxygen consumption rates and the origins of endothermy.

This is roughly consistent with the human ailment odontoma, the most frequent type of odontogenic tumour, which previously only extended a few million years back in the fossil record.

[52] Following the extinction of the dinocephalians and (in South Africa) the basal therocephalians Scylacosauridae and Lycosuchidae, gorgonopsians evolved from small and uncommon forms into large apex predators.

[53] During the Upper Permian, the South African Beaufort Group was a semi-arid cold steppe featuring large, seasonal (ephemeral) rivers and floodplains draining water sources much farther north into the Karoo Sea, with some occurrences of flash floods after sudden, heavy rainfall;[54][55] the distribution of carbonates is consistent with present-day caliche deposits which form in climates with an average temperature of 16–20 °C (61–68 °F) and 100–500 mm (3.9–19.7 in) of seasonal rainfall.

[55] The gorgonopsian-bearing Salarevskian Formation in western Russia was also probably deposited in a semi-arid environment with highly seasonal rainfall, and featured hygrophyte and halophyte plants in coastal areas, as well as more drought-resistant conifers at higher elevations.

The resultant massive spike in greenhouse gases caused rapid aridification due to: temperature spike (as much as 8–10 °C at the equator, with average equatorial temperatures of 32–35 °C, or 90–95 °F, at the beginning of the Triassic), acid rain (with pH as low as 2 or 3 during eruption and 4 globally, and the subsequent dearth of forests for the first 10 million years of the Triassic), frequent wildfires (though they were already rather common throughout the Permian), and potential breakdown of the ozone layer (possibly briefly increasing UV radiation bombardment by 400% at the equator and 5000% at the poles).