Gospel of Marcion

[3][4][5][6][7] There are debates as to whether several verses of Marcion's gospel are attested firsthand in a manuscript in Papyrus 69, a hypothesis proposed by Claire Clivaz and put into practice by Jason BeDuhn.

[1][3] Thorough, meticulous, yet highly divergent reconstructions of much or all of the content of the Gospel of Marcion have been made by several scholars, including August Hahn (1832),[8] Theodor Zahn (1892), Adolf von Harnack (1921),[9] Kenji Tsutsui (1992), Jason BeDuhn (2013),[3] Dieter T. Roth (2015),[10] Matthias Klinghardt (2015/2020, 2021),[4] and Andrea Nicolotti (2019).

The gospel began, roughly, as follows: In the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, Jesus descended into Capernaum, a city in Galilee, and was teaching on the Sabbath days.

Luke 3:1a, 4:31)Other Lukan passages that did not appear in Marcion's gospel include the parables of the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son.

The differences in the texts below are interpreted by advocates of this hypothesis as evidence of Marcion editing Luke to omit the Hebrew Prophets and to better support a dualistic view of the earth as evil.

Late 19th- and early 20th-century theologian Adolf von Harnack, in agreement with the traditional account of Marcion as revisionist, theorized that Marcion believed there could be only one true gospel, all others being fabrications by pro-Jewish elements, determined to sustain worship of Yahweh; and that the true gospel was given directly to Paul the Apostle by Christ himself, but was later corrupted by those same elements who also corrupted the Pauline epistles.

[21] These scholars see a consistent pattern running in the opposite direction, that Marcion's Gospel usually attests simpler, earlier textual traditions than corresponding content in canonical Luke both at the micro- and macro-level.

Schmidt,[24] Leonhard Bertholdt,[25] Johann Gottfried Eichhorn, John Knox,[15]: 110 Karl Reinhold Köstlin, Joseph B. Tyson,[26] and Jason BeDuhn.

[28] This position has been supported by scholars such as Albrecht Ritschl,[29] Ferdinand Christian Baur,[30] Paul-Louis Couchoud, Georges Ory, John Townsend, R. Joseph Hoffman,[31] Matthias Klinghardt,[21] Markus Vinzent,[32][33][34] and David Trobisch.

Thirdly, John Knox[15] and Joseph Tyson[39] (both using Harnack's edition), and more recently Daniel A. Smith[40] (using Roth's edition), have all put forth statistical analyses showing that Lukan single traditions are disproportionately lacking in the Gospel of Marcion, while double and triple traditions are disproportionately present.

[6] Like several 19th century scholars, Knox, Tyson, Vinzent, and Klinghardt have extended the Schwegler hypothesis to include the canonical Book of Acts, arguing that it is an anti-Marcionite work.

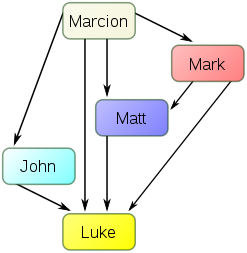

In Klinghardt's view, this model elegantly accounts for the double tradition— material shared by Matthew and Luke, but not Mark— without appealing to purely hypothetical documents, such as the Q source.