Gothic language

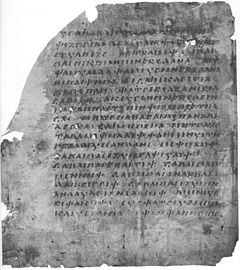

It is known primarily from the Codex Argenteus, a 6th-century copy of a 4th-century Bible translation, and is the only East Germanic language with a sizeable text corpus.

All others, including Burgundian and Vandalic, are known, if at all, only from proper names that survived in historical accounts, and from loanwords in other, mainly Romance, languages.

A language known as Crimean Gothic survived in the lower Danube area and in isolated mountain regions in Crimea as late as the second half of the 18th century.

[5][6] The existence of such early attested texts makes Gothic a language of considerable interest in comparative linguistics.

Most Gothic-language sources are translations or glosses of other languages (namely, Greek), so foreign linguistic elements most certainly influenced the texts.

In De incrementis ecclesiae Christianae (840–842), Walafrid Strabo, a Frankish monk who lived in Swabia, writes of a group of monks who reported that even then certain peoples in Scythia (Dobruja), especially around Tomis, spoke a sermo Theotiscus ('Germanic language'), the language of the Gothic translation of the Bible, and that they used such a liturgy.

Some scholars (such as Braune) claim that it was derived from the Greek alphabet only while others maintain that there are some Gothic letters of Runic or Latin origin.

Just as in other Germanic languages, the free moving Proto-Indo-European accent was replaced with one fixed on the first syllable of simple words.

In most compound words, the location of the stress depends on the type of compound: For example, with comparable words from modern Germanic languages: Gothic preserves many archaic Indo-European features that are not always present in modern Germanic languages, in particular the rich Indo-European declension system.

Although descriptive adjectives in Gothic (as well as superlatives ending in -ist and -ost) and the past participle may take both definite and indefinite forms, some adjectival words are restricted to one variant.

One particularly noteworthy characteristic is the preservation of the dual number, referring to two people or things; the plural was used only for quantities greater than two.

While proto-Indo-European used the dual for all grammatical categories that took a number (as did Classical Greek and Sanskrit), most Old Germanic languages are unusual in that they preserved it only for pronouns.

The bulk of Gothic verbs follow the type of Indo-European conjugation called 'thematic' because they insert a vowel derived from the reconstructed proto-Indo-European phonemes *e or *o between roots and inflexional suffixes.

The Gothic word wáit, from the proto-Indo-European *woid-h2e ("to see" in the perfect), corresponds exactly to its Sanskrit cognate véda and in Greek to ϝοἶδα.

In both cases, the verb follows the complement, giving weight to the theory that basic word order in Gothic is object–verb.

[27] However, this pattern is reversed in imperatives and negations:[28] And in a wh-question the verb directly follows the question word:[28] Gothic has two clitic particles placed in the second position in a sentence, in accordance with Wackernagel's Law.

fotjus, can be contrasted with English foot : feet, German Fuß : Füße, Old Norse fótr : fœtr, Danish fod : fødder.

Proto-Germanic *z remains in Gothic as z or is devoiced to s. In North and West Germanic, *z changes to r by rhotacism: Gothic retains a morphological passive voice inherited from Indo-European but unattested in all other Germanic languages except for the single fossilised form preserved in, for example, Old English hātte or Runic Norse (c. 400) haitē "am called", derived from Proto-Germanic *haitaną "to call, command".

The morphological passive in North Germanic languages (Swedish gör "does", görs "is being done") originates from the Old Norse middle voice, which is an innovation not inherited from Indo-European.

Gothic possesses a number of verbs which form their preterite by reduplication, another archaic feature inherited from Indo-European.

While traces of this category survived elsewhere in Germanic, the phenomenon is largely obscured in these other languages by later sound changes and analogy.

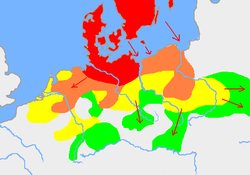

It is based partly on historical claims: for example, Jordanes, writing in the 6th century, ascribes to the Goths a Scandinavian origin.

and ggw, and Old Norse ggj and ggv ("Holtzmann's Law"), in contrast to West Germanic where they remained as semivowels.

That is, if a parent language splits into three daughters A, B and C, and C innovates in a particular area but A and B do not change, A and B will appear to agree against C. That shared retention in A and B is not necessarily indicative of any special relationship between the two.

Another commonly-given example involves Gothic and Old Norse verbs with the ending -t in the 2nd person singular preterite indicative, and the West Germanic languages have -i.

Frederik Kortlandt has agreed with Mańczak's hypothesis, stating: "I think that his argument is correct and that it is time to abandon Iordanes' classic view that the Goths came from Scandinavia.

[36] The Thorvaldsen museum also has an alliterative poem, "Thunravalds Sunau", from 1841 by Massmann, the first publisher of the Skeireins, written in the Gothic language.

[38] In 2012, professor Bjarne Simmelkjær Hansen of the University of Copenhagen published a translation into Gothic of Adeste Fideles for Roots of Europe.

[39] In Fleurs du Mal, an online magazine for art and literature, the poem Overvloed of Dutch poet Bert Bevers appeared in a Gothic translation.

[40][full citation needed] Alice in Wonderland has been translated into Gothic (Balþos Gadedeis Aþalhaidais in Sildaleikalanda) by David Carlton in 2015 and is published by Michael Everson.