Gotse Delchev

[12] Also for him, like for many prominent people,[13] originating from an area with mixed population,[14] the idea of being 'Macedonian' acquired the importance of a certain native loyalty, that constructed a specific spirit of "local patriotism"[15][16] and "multi-ethnic regionalism".

[19][20][21] In this way, his outlook included a wide range of such disparate ideas like Bulgarian patriotism, Macedonian regionalism, anti-nationalism, and incipient socialism.

[22][23] As a result, his political agenda became the establishment through revolution of an autonomous Macedono-Adrianople supranational state into the framework of the Ottoman Empire, as a prelude to its incorporation within a future Balkan Federation.

He was born to a large family on 4 February 1872 (23 January according to the Julian calendar) in Kılkış (Kukush), then in the Ottoman Empire (today in Greece), to Nikola and Sultana.

[38] He also read widely in the town's chitalishte (community cultural center), where he was impressed with revolutionary books, and was especially imbued with thoughts of the liberation of Bulgaria.

In June 1892, Delchev and the journalist Kosta Shahov, a chairman of the Young Macedonian Literary Society, met in Sofia with the bookseller from Thessaloniki, Ivan Hadzhinikolov.

Delchev explained that he had no intention of remaining an officer and promised after graduating from the Military School, he would return to Macedonia to join the organization.

[49] However, as a rule, most of SMAC's leaders were officers with stronger connections with the governments, waging terrorist struggle against the Ottomans in the hope of provoking a war and thus Bulgarian annexation of both areas.

In late 1895 he arrived in Bulgaria's capital Sofia from the name of the "Bulgarian Central Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Revolutionary Committee" to prevent any foreign interference in its work.

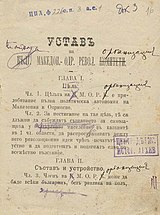

[50] In 1896, he advocated for the establishment of a secret revolutionary network, that would prepare the population for an armed uprising against the Ottoman rule, based on Levski's example.

[11] After spending the next school year (1895/1896) as a teacher in the town of Bansko, in May 1896 he was arrested by the Ottoman authorities as a person suspected of revolutionary activity and spent about a month in jail.

[53] Delchev envisioned independent production of weapons and traveled in 1897 to Odessa,[29] where he met with Armenian revolutionaries Stepan Zorian and Christapor Mikaelian to exchange terrorist skills and especially bomb-making.

[58] After the assassination of the Romanian newspaper editor Ștefan Mihăileanu in July, who had published unflattering remarks about the Macedonian affairs, Bulgaria and Romania were brought to the brink of war.

For a short time in the late 1890s Bulgarian lieutenant Boris Sarafov, who was a former schoolmate of Delchev became its leader, as he was promoted as a candidate by him and Petrov.

Towards the end of March 1903, Delchev with his detachment destroyed the railway bridge over the Angista river, aiming to test the new guerrilla tactics.

[10][72] He was killed on 4 May 1903, with a shot to the chest,[43] in a skirmish with Ottoman troops led by his former schoolmate Hussein Tefikov in the village of Banitsa.

[2] After being identified by the local authorities in Serres, the bodies of Delchev and his comrade, Dimitar Gushtanov, were buried in a common grave in Banitsa.

[76] Two of his brothers, Mitso and Milan were also killed fighting against the Ottomans as militants in the SMARO chetas of the Bulgarian voivodas Hristo Chernopeev and Krstjo Asenov in 1901 and 1903, respectively.

[83][84] The international, cosmopolitan views of Delchev could be summarized in his proverbial sentence: "I understand the world solely as a field for cultural competition among the peoples".

[85][86] Per MacDermott, his saying presupposes a world without political and economic conflicts and one which has a very high degree of mutual friendship and co-operation on an international level.

[91] His main goal, along with the other revolutionaries, was the implementation of Article 23 of the treaty, aimed at acquiring full autonomy of Macedonia and the Adrianople.

[92] Delchev, like other left-wing activists, vaguely determined the bonds in the future common Macedonian-Adrianople autonomous region on the one hand,[93] and on the other between it, the Principality of Bulgaria, and de facto annexed Eastern Rumelia.

[95] Per Bulgarian academic sources and his contemporaries, Delchev supported Macedonia's eventual incorporation into Bulgaria,[96][97] or its inclusion into a future Balkan Confederative Republic.

However, during the war these ideas were supported by the pro-Yugoslav Macedonian communist partisans, who strengthened their positions in 1943, referring to the ideals of Gotse Delchev.

[110] In 1946, communist activist Vasil Ivanovski acknowledged that Delchev did not have a clear view of a "Macedonian national character", but stated that his struggle made the free and autonomous Macedonia a possibility.

[109] On 7 October 1946, under pressure from Moscow,[111] as part of the policy to foster the development of Macedonian national consciousness, Delchev's remains were transported to Skopje.

Delchev was described in SR Macedonia not only as an anti-Ottoman freedom fighter, but also as a hero, who had opposed the aggressive aspirations of the pro-Bulgarian factions in the liberation movement.

[127] On 2 August 2017, the Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borisov and his Macedonian colleague Zoran Zaev placed wreaths at the grave of Delchev on the occasion of the 114th anniversary of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising.

[136] Per anthropologist Keith Brown and political scientist Alexis Heraclides, the identity of Delchev and other IMRO figures is "open to different interpretations",[137] that are incompatible with the views of modern Balkan nationalisms.

[152] Three citizens were detained, fined and banned from entering the country for 3 years, due to attempting to physically assault policemen.