Government of Japan

The Government of Japan is based in the capital of Tokyo, where the National Diet Building, the Imperial Palace, the Supreme Court, the Prime Minister's Office and the ministries are all located.

During this period, effective power of the government resided in the Shōgun, who officially ruled the country in the name of the Emperor.

In 1889, the Meiji Constitution was adopted in a move to strengthen Japan to the level of western nations, resulting in the first parliamentary system in Asia.

It merged the ancient court nobility of the Heian period, the kuge, and the former daimyō, feudal lords subordinate to the shōgun.

[21] As of 2020, the Japan Research Institute found the national government is mostly analog, because only 7.5% (4,000 of the 55,000) administrative procedures can be completed entirely online.

The House was expected to be dissolved on the advice of the prime minister, but was temporarily unable to do so for the next general election, as both the Emperor and Empress were visiting Canada.

Today, a legacy has somewhat continued for a retired prime minister who still wields considerable power, to be called a Shadow Shogun.

[31] According to the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, Japan was founded by the Imperial House in 660 BC by Emperor Jimmu.

[33] He is, according to Japanese mythology, the direct descendant of Amaterasu, the sun goddess of the native Shinto religion, through Ninigi, his great-grandfather.

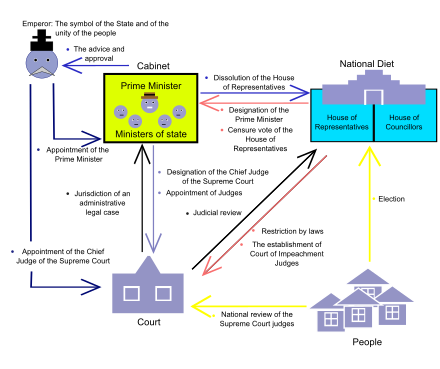

[4] Explicitly defined to be the source of executive power, it is in practice, however, mainly exercised by the prime minister.

[4] Both houses of the National Diet designates the Prime Minister with a ballot cast under the run-off system.

[3] Article 73 of the Constitution of Japan expects the Cabinet to perform the following functions, in addition to general administration: Under the Constitution, all laws and cabinet orders must be signed by the competent Minister and countersigned by the Prime Minister, before being formally promulgated by the Emperor.

Empowered by the Constitution to be "the highest organ of State power" and the only "sole law-making organ of the State", its houses are both directly elected under a parallel voting system and is ensured by the Constitution to have no discrimination on the qualifications of each members; whether be it based on "race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income".

[53] The Constitution also enables both houses to conduct investigations in relation to government, demand the presence and testimony of witnesses, and the production of records, as well as allowing either house of the Diet to demand the presence of the Prime Minister or the other Minister of State, in order to give answers or explanations whenever so required.

[54] Under the provisions of the Constitution and by law, all adults aged over 18 are eligible to vote, with a secret ballot and a universal suffrage, and those elected have certain protections from apprehension while the Diet is in session.

The Cabinet can also, at will, convoke extraordinary sessions of the Diet and is required to, when a quarter or more of the total members of either house demands it.

Each year, and when required, the National Diet is convoked at the House of Councillors, on the advice of the Cabinet, for an extra or an ordinary session, by the Emperor.

[67] The Constitution also explicitly denies any power for executive organs or agencies to administer disciplinary actions against judges.

[70] The Legal system in Japan has been historically influenced by Chinese law; developing independently during the Edo period through texts such as Kujikata Osadamegaki.

[88] The result of this power is a high level of organizational and policy standardization among the different local jurisdictions allowing them to preserve the uniqueness of their prefecture, city, or town.

Some of the more collectivist jurisdictions, such as Tokyo and Kyoto, have experimented with policies in such areas as social welfare that later were adopted by the national government.

In order to attain city status, a jurisdiction must have at least 500,000 inhabitants, 60 percent of whom are engaged in urban occupations.

They often consist of a number of rural hamlets containing several thousand people connected to one another through the formally imposed framework of village administration.

[89][90] Each jurisdiction has a chief executive, called a governor (知事, chiji) in prefectures and a mayor (市町村長, shichōsonchō) in municipalities.

Ordinances, similar to statutes in the national system, are passed by the assembly and may impose limited criminal penalties for violations (up to 2 years in prison and/or 1 million yen in fines).

Regulations, similar to cabinet orders in the national system, are passed by the executive unilaterally, are superseded by any conflicting ordinances, and may only impose a fine of up to 50,000 yen.

Moreover, in many local communities candidates from different parties tend to share similar concerns, e.g., regarding depopulation and how to attract new residents.

He writes, "“Populationism” assumes the necessity of maintaining and increasing the number of residents for the future and vitality of the municipality.

These two ideas, though not fully-fledged ideologies, are assumptions guiding the behavior of political actors in municipalities in Japan when dealing with depopulation.

"[95] All prefectures are required to maintain departments of general affairs, finance, welfare, health, and labor.