Governor's Body Guard of Light Horse

Men from the unit were deployed during the Castle Hill convict rebellion of 1804 and a trooper of the Guard assisted in the capture of two of the rebel leaders.

King provided horses and cavalry equipment from colony government funds and authorised a 1 shilling per day pay rise to the corporal and 6 pence to the privates.

[1] The Guard carried the governor's despatches sent to far-flung garrison outposts across the colony and was particularly busy in the early years due to unrest among newly arrived Irish convicts.

Many of these men were Republican revolutionaries, members of the Society of United Irishmen sentenced to transportation following capture after the 21 June 1798 Battle of Vinegar Hill.

A series of disputes culminated in the wounding of Paterson in a duel with one of his captains, John Macarthur, who was heavily involved in the rum trade.

Historian David Clune notes that because of King's efforts to restrict the rum trade, safeguard the colony's women, children and aborigines, and stamp out corruption in use of convict labour and land grants, the Guard was "viewed more with amusement than anger in London".

[8] King placed the Guard under the command of Captain John Piper of the New South Wales Corps in February 1803 to assist with the recapture of escaped convicts near Parramatta.

[10] That November, King pardoned George Bridges Bellasis, a former lieutenant in an East India Company artillery unit who had been transported for killing a fellow officer in a duel.

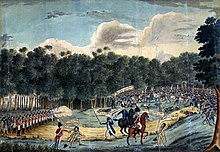

The painting depicts Anlezark (erroneously shown as a corporal) drawing his pistol and ordering a rebel leader: "Croppy lay down".

[12] Anlezark, a convicted burglar and fourteen-year British Army cavalry veteran, was promoted to corporal in the Guard in May 1804, replacing the existing NCO who was discharged for "gross abuse to a superintendent".

[3] The Guard's actions in quelling the rebellion and a favourable report from Johnston led King to propose increasing the unit to thirty men.

Johnston, who now commanded the New South Wales Corps in Sydney, marched on Government House and arrested Bligh in an act known as the Rum Rebellion.

[17] He sought to increase their strength to twelve men but when news of this reached the British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, the Earl of Liverpool, he refused to grant permission and demanded the unit be disbanded.

In 1812, Macquarie requested this decision be rescinded as most other British colonies had a unit of regular or militia cavalry at their disposal; he claimed that he "felt very much hurt" at being "singled out as Undeserving this Honor".

[19][20] The Guard sergeant from 1808 to 1822 was Charles Whalan who became good friends with Macquarie, accompanying him on personal holidays and being one of the last people to see him off on his return to Britain in 1821.

When newly arrived governor Richard Bourke disclosed an expenditure of £112 16s 6d in his December 1831 report, this was queried by the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Viscount Goderich, who ordered the unit disbanded.

[1][23] Sargent notes that the ambiguous status of the Governor's Body Guard of Light Horse was indicative of the difficulty the British government had in understanding the colony in this period.

The British were keen to restrict expenses incurred by the government of the colony and, without an understanding of the local conditions, saw no reason for the governor to have a personal bodyguard.