East India Company

Company-ruled areas in the region gradually expanded after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 and by 1858 most of modern India, Pakistan and Bangladesh was either ruled by the company or princely states closely tied to it by treaty.

[14] Elizabeth granted her permission and in 1591, James Lancaster in the Bonaventure with two other ships,[15] financed by the Levant Company, sailed from England around the Cape of Good Hope to the Arabian Sea, becoming the first English expedition to reach India that way.

[13] The biggest prize that galvanised English trade was the seizure of a large Portuguese carrack, the Madre de Deus, by Walter Raleigh and the Earl of Cumberland at the Battle of Flores on 13 August 1592.

[17] When she was brought in to Dartmouth she was the largest vessel ever seen in England and she carried chests of jewels, pearls, gold, silver coins, ambergris, cloth, tapestries, pepper, cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, benjamin (a highly aromatic balsamic resin used for perfumes and medicines), red dye, cochineal and ebony.

[18] Equally valuable was the ship's rutter (mariner's handbook) containing vital information on the China, India, and Japan trade routes.

[16]: 1–2 On 22 September, the group stated their intention "to venture in the pretended voyage to the East Indies (the which it may please the Lord to prosper)" and to themselves invest £30,133 (over £4,000,000 in today's money).

[13] For a period of fifteen years, the charter awarded the company a monopoly[25] on English trade with all countries east of the Cape of Good Hope and west of the Straits of Magellan.

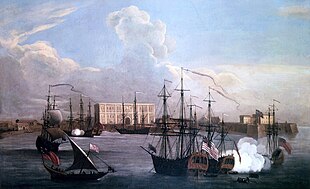

By tradition, business was initially transacted at the Nags Head Inn, opposite St Botolph's church in Bishopsgate, before moving to East India House on Leadenhall Street.

[29] The following year, whilst sailing in the Malacca Straits, Lancaster took the rich 1,200 ton Portuguese carrack Sao Thome carrying pepper and spices.

The Dutch, better financed and supported by their government, gained the upper hand by establishing a stronghold in the spice islands (now Indonesia), enforcing a near-monopoly through aggressive policies that eventually drove the EIC to seek trade opportunities in India instead.

The company decided to explore the feasibility of a foothold in mainland India, with official sanction from both Britain and the Mughal Empire, and requested that the Crown launch a diplomatic mission.

[citation needed] In 1615, James I instructed Sir Thomas Roe to visit the Mughal Emperor Nur-ud-din Salim Jahangir (r. 1605–1627) to arrange for a commercial treaty that would give the company exclusive rights to reside and establish factories in Surat and other areas.

This compelled the company to formally abandon their efforts in the Spice Islands, and turn their attention to Bengal where, by this time, they were making steady, if less exciting, profits.

[citation needed] In the 18th Century, the primary source of the Company's profits in Bengal became taxation in conquered and controlled provinces, as the factories became fortresses and administrative hubs for networks of tax collectors that expanded into enormous cities.

With reduced Portuguese and Spanish influence in the region, the EIC and VOC entered a period of intense competition, resulting in the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 17th and 18th centuries.

Within the first two decades of the 17th century, the Dutch East India Company or Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, (VOC) was the wealthiest commercial operation in the world with 50,000 employees worldwide and a private fleet of 200 ships.

Saris was the chief factor of the EIC's trading post in Java, and with the assistance of William Adams, an English sailor who had arrived in Japan in 1600, he was able to gain permission from the ruler to establish a commercial house in Hirado on the Japanese island of Kyushu: We give free license to the subjects of the King of Great Britaine, Sir Thomas Smythe, Governor and Company of the East Indian Merchants and Adventurers forever safely come into any of our ports of our Empire of Japan with their shippes and merchandise, without any hindrance to them or their goods, and to abide, buy, sell and barter according to their own manner with all nations, to tarry here as long as they think good, and to depart at their pleasure.

[54]Unable to obtain Japanese raw silk for export to China, and with their trading area reduced to Hirado and Nagasaki from 1616 onwards, the company closed its factory in 1623.

To appease Aurangzeb, the East India Company promised to pay all financial reparations, while Parliament declared the pirates hostis humani generis ("the enemy of humanity").

To appease Emperor Aurangzeb and particularly his Grand Vizier Asad Khan, Parliament exempted Every from all of the Acts of Grace (pardons) and amnesties it would subsequently issue to other pirates.

[63] Company started selling opium to Chinese merchants in the 1770s in exchange for goods like porcelain and tea,[64] causing a series of opioid addiction outbreaks across China in 1820.

[70] The prosperity that the officers of the company enjoyed allowed them to return to Britain and establish sprawling estates and businesses, and to obtain political power, such as seats in the House of Commons.

In 1742, fearing the monetary consequences of a war, the British government agreed to extend the deadline for the licensed exclusive trade by the company in India until 1783, in return for a further loan of £1 million.

Demand for Indian commodities was boosted by the need to sustain troops and the economy during the war, and by the increased availability of raw materials and efficient methods of production.

[76]Sir John Banks, a businessman from Kent who negotiated an agreement between the king and the company, began his career in a syndicate arranging contracts for victualling the navy, an interest he kept up for most of his life.

[79][better source needed] By the Treaty of Paris, France regained the five establishments captured by the British during the war (Pondichéry, Mahe, Karaikal, Yanam and Chandernagar) but was prevented from erecting fortifications and keeping troops in Bengal (art.

In return, the shareholders voted to accept an annual dividend of 10.5%, guaranteed for forty years, likewise to be funded from India, with a final pay-off to redeem outstanding shares.

[89] The company remained in existence in vestigial form, continuing to manage the tea trade on behalf of the British Government (and the supply of Saint Helena) until the East India Stock Dividend Redemption Act 1873 came into effect, on 1 January 1874.

The East India Company's merchant mark consisted of a "Sign of Four" atop a heart within which was a saltire between the lower arms of which were the initials "EIC".

East Indiamen were large and strongly built, and when the Royal Navy was desperate for vessels to escort merchant convoys, it bought several of them to convert to warships.