Greco-Buddhism

[5][6][7][8][9][10] Cultural interactions between ancient Greece and Buddhism date back to Greek forays into the Indian subcontinent from the time of Alexander the Great.

He founded several cities in his new territories in the areas of the Amu Darya and Bactria, and Greek settlements further extended to the Khyber Pass, Gandhara (see Taxila), and the Punjab.

According to a legend preserved in the Pali Canon, two merchant brothers from Kamsabhoga in Bactria, Tapassu and Bhallika, visited Gautama Buddha and became his disciples.

Emperor Seleucus I Nicator came to a marital agreement as part of a peace treaty,[18] and several Greeks, such as the historian Megasthenes, resided at the Mauryan court.

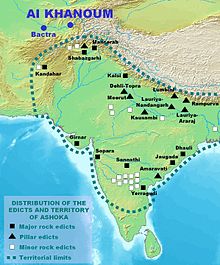

Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka embraced the Buddhist faith and became a great proselytizer in the line of the traditional Pali canon of Theravada Buddhism, insisting on non-violence to humans and animals (ahimsa), and general precepts regulating the life of laypeople.

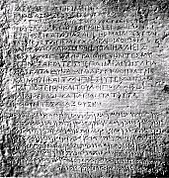

The edicts name each of the rulers of the Hellenistic period: The conquest by Dharma has been won here, on the borders, and even six hundred yojanas [4,000 miles] away, where the Greek king Antiochos (Antiyoga) rules, and beyond there where the four kings named Ptolemy (Turamaya), Antigonos (Antikini), Magas (Maka) and Alexander (Alikasu[n]dara) rule, likewise in the south among the Cholas, the Pandyas, and as far as Tamraparni.

[22] Alexander had established in Bactria several cities (such as Ai-Khanoum and Bagram) and an administration that were to last more than two centuries under the Seleucid Empire and the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, all the time in direct contact with Indian territory.

Megasthenes sent detailed reports on Indian religions, which were circulated and quoted throughout the Classical world for centuries:[23] Megasthenes makes a different division of the philosophers, saying that they are of two kinds, one of which he calls the Brachmanes, and the other the Sarmanes...The Greco-Bactrians maintained a strong Hellenistic culture at the door of India during the rule of the Maurya Empire in India, as exemplified by the archaeological site of Ai-Khanoum.

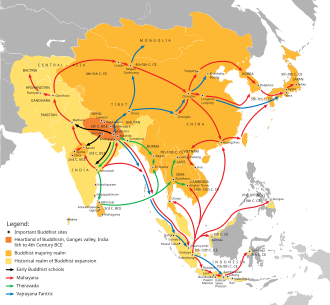

Buddhism prospered under the Indo-Greek kings, and it has been suggested that their invasion of India was intended to protect the Buddhist faith from the religious persecutions of the Shungas (185–73 BC), who had overthrown the Mauryans.

Zarmanochegas was a śramana (possibly, but not necessarily a Buddhist) who, according to ancient historians such as Strabo, Cassius Dio, and Nicolaus of Damascus traveled to Antioch and Athens while Augustus (died 14 AD) was ruling the Roman Empire.

According to the Milinda Pañha, at the end of his reign Menander I became a Buddhist arhat,[27] a fact also echoed by Plutarch, who explains that his relics were shared and enshrined.

When the Zoroastrian Indo-Parthian Kingdom invaded North India in the 1st century AD, they adopted a large part of the symbolism of Indo-Greek coinage, but refrained from ever using the elephant, suggesting that its meaning was not merely geographical.

Finally, after the reign of Menander I, several Indo-Greek rulers, such as Amyntas Nikator, Nicias, Peukolaos, Hermaeus, Hippostratos and Menander II, depicted themselves or their Greek deities forming with the right hand a benediction gesture identical to the Buddhist vitarka mudra (thumb and index joined together, with other fingers extended), which in Buddhism signifies the transmission of Buddha's teaching.

[32] The Kushan Empire, one of the five tribes of the Yuezhi, settled in Bactria around 125 BC, displacing the Greco-Bactrians and invading the northern parts of Pakistan and India from around 1 AD.

The Kushan King Kanishka, who honored Zoroastrian, Greek and Brahmanic deities as well as the Buddha and was famous for his religious syncretism, convened the Fourth Buddhist council around 100 in Kashmir in order to redact the Sarvastivadin canon.

[42] A large quantity of sculptures combining Buddhist and purely Hellenistic styles and iconography were excavated at the modern site of Hadda, Afghanistan.

"[43] The Greek stylistic influence on the representation of the Buddha, through its idealistic realism, also permitted a very accessible, understandable and attractive visualization of the ultimate state of enlightenment described by Buddhism, allowing it to reach a wider audience: One of the distinguishing features of the Gandharan school of art that emerged in north-west India is that it has been clearly influenced by the naturalism of the Classical Greek style.

These figures are inspiring because they do not only depict the goal, but also the sense that people like us can achieve it if we try.During the following centuries, this anthropomorphic representation of the Buddha defined the canon of Buddhist art, but progressively evolved to incorporate more Indian and Asian elements.

[45][46] In Japan, this expression further translated into the wrath-filled and muscular Niō guardian gods of the Buddha, standing today at the entrance of many Buddhist temples.

[47] In addition, forms such as garland-bearing cherubs, vine scrolls, and such semihuman creatures as the centaur and triton, are part of the repertory of Hellenistic art introduced by Greco-Roman artists in the service of the Kushan court.

XXIX), who led 30,000 Buddhist monks from "the Greek city of Alasandra" (Alexandria of the Caucasus, around 150 km north of today's Kabul in Afghanistan), to Sri Lanka for the dedication of the Great Stupa in Anuradhapura.

Dharmaraksita (Sanskrit), or Dhammarakkhita (Pali) (translation: Protected by the Dharma), was one of the missionaries sent by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka to proselytize the Buddhist faith.

Zarmanochegas (Zarmarus) (Ζαρμανοχηγὰς) was a monk of the Sramana tradition (possibly, but not necessarily a Buddhist) who, according to ancient historians such as Strabo and Dio Cassius, met Nicholas of Damascus in Antioch while Augustus (d. 14 AD) was ruling the Roman Empire, and shortly thereafter proceeded to Athens where he burnt himself to death.

Another century later the Christian church father Clement of Alexandria (d. 215 AD) mentioned Buddha by name in his Stromata (Bk I, Ch XV): "The Indian gymnosophists are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers.

And those of the Sarmanæ who are called "Hylobii" neither inhabit cities, nor have roofs over them, but are clothed in the bark of trees, feed on nuts, and drink water in their hands.

[54] The pre-Christian monastic order of the Therapeutae is possibly a deformation of the Pāli word "Theravāda",[55] a form of Buddhism, and the movement may have "almost entirely drawn (its) inspiration from the teaching and practices of Buddhist asceticism".

[64][65][66] While the Hellenistic influences in Gandharan Buddhist art have been widely accepted[42][67][68] it remains a matter of controversy among art historians whether the non-Indian characteristics of Gandhāran sculpture reflect a continuous Greek tradition rooted in Alexander’s conquests in Bactria, subsequent contacts with later traditions of the Hellenistic east, direct communication with contemporary artists from the Roman empire, or some complex conjunction of such sources.

[69] Examples include statues of bodhisattvas adorned with royal jewellery (bracelets and torques) and amulet boxes, the contrapposto stance, an emphasis on draperies, and a plethora of Dionysian themes.

She states that she does "not exclude the possibility that some phenomena within Buddhism may be interpreted as a manifestation of syncretism between Greek and Buddhist elements, but the term Greco-Buddhism applies only to certain aspects and not to the entirety of Greco-Buddhist relations".

[74] Johanna Hanink has attributed the concept of "Greco-Buddhist art" to a European scholarly inability to accept that natives could have developed "the pleasing proportions and elegant poses of sculptures from ancient Gandhara", citing Michael Falser and arguing that the entire notion of "Buddhist art with a Greek 'essence'" is a colonial imposition that originated during British rule in India.

Obverse : Alexander being crowned by Nike .

Reverse : Alexander attacking King Porus on his elephant.

Silver. British Museum .